The Chevrolet Corvette SS was the car that truly allowed Zora Arkus-Duntov, the “father of the Corvette”, to demonstrate his creativity and engineering expertise. It was a car that was given the opportunity to demonstrate its potential, but denied the chance to achieve what it had in all probability been created for, a credible showing at the 24 Hours Le Mans.

Despite the Corvette SS being denied the opportunity to demonstrate its capabilities at Le Mans a team of ordinary Corvettes would compete in the 1960 24 Hours Le Mans, and would emerge with a respectable eighth place finish.

Fast Facts

- The Project XP-64 Chevrolet Corvette SS was a factory designed and built sports racing car created specifically to compete at the 24 Hours Le Mans in 1957.

- The car was the work of a team led by the “Father of the Corvette” Zora Arkus-Duntov.

- Despite making an impressive showing at the 1957 12 Hours of Sebring the Corvette SS of Project XP-64 was unexpectedly denied the chance to race at Le Mans because The Automobile Manufacturers Association (AMA) of the United States got the agreement of all US makers to end factory racing.

- The Project XP-64 Corvette SS finished up being donated to the Indianapolis Motor Speedway Museum from where it made various appearances over the decades.

- This unique car is coming up for sale by RM Sotheby’s at their Miami 2025 sale.

The Chevrolet Corvette heralded in a new identity for General Motor’s Chevrolet division. Chevrolet were up to that time GM’s affordable car make. Car’s for utilitarian use by folks who did not have the fat wallets expected of Buick and Cadillac buyers for example.

In the post World War II period there were some new influences being imported into the United States, and one of the most influential for the US automobile industry were the British and European sports cars that many US servicemen brought back with them when they returned home to the USA.

The attraction of these sports cars was not just the fact that they were fast, but that they were exotic, and that they were enormous fun to drive. They were challenging to drive, but the challenge presented a large part of the enjoyment. These mostly open top two-seater sports cars provided a driving experience about as close to being on a motorcycle as can be had on four wheels.

There were decision makers at General Motors who could see that there was a potential new market that could be exploited. Many of the European and British sports cars that were being imported into the US were in technology terms not particularly different to existing US automotive manufacturing technology. The front suspension of these cars was typically upper and lower wishbones with coil springs, while at the rear it was common to find a beam axle and leaf springs.

Disc brakes were being developed in Britain at that time but in the early 1950’s had not become mainstream on most sports cars – British maker Jaguar were among the first to employ this new brake technology.

General Motors was persuaded to dip a tentative toe into the challenge of making a sports car in 1951 under the influence of designer Harley Earl.

This new two-seater sports car was to be created under the Chevrolet banner and it was to be done as un-adventurously and cheaply as it possibly could. It was to be called the “Corvette”, a name that would be familiar to Navy and Marines servicemen as the small, agile and fast warships they were familiar with from their military service.

Projects done “on the cheap” are typically not immediately successful and this new sports car experiment was to be done as a bit of a “parts bin special” with a newfangled plastic body. This pretty much ensured that it was not initially successful, in fact it was almost axed by General Motors and probably the only thing that saved it from oblivion was that the folks over at rival car maker Ford decided to make a two-seater sporty car called the Ford Thunderbird pretty much forcing GM to match them and try to beat them in that new market segment.

At that point, because GM had to take the Corvette seriously in order to outdo Ford, they committed money and resources to make the car a success.

The Corvette made its debut at the 1953 General Motors’ Motorama show, held at the Waldorf Astoria in New York City. One of the many who saw the show car was a Russian immigrant named Zachary Arkus-Duntov – better know as Zora Arkus-Duntov.

Arkus-Duntov was impressed by the overall concept of the display car but his background in automotive engineering and in motorsport revealed to him the shortcomings of the car, and also revealed to him what he would do if given the opportunity to improve it.

Arkus-Duntov decided to see if a window of opportunity could be opened to him and he wrote a letter to Chevrolet’s Chief Engineer Ed Cole: a letter that was an expression of interest in working on the car and he also submitted a technical paper on how to determine a car’s top speed analytically.

Arkus-Duntov’s background included his having worked for British sports and racing car maker Allard on cars to compete in the 24 Hours Le Mans motor race and his depth of knowledge and experience interested General Motors enough for them to hire him.

Once he was employed by General Motors Arkus-Duntov submitted a memo titled “Thoughts Pertaining to Youth, Hot Rodders and Chevrolet”, in which he outlined strategies which Chevrolet could employ to compete with Ford, especially through the use of high performance cars and racing, and to help achieve public acceptance of the Chevrolet V8 engine in passenger cars.

This memo created interest in the potential for motorsport to increase sales and paved the way for the creation of high performance competition cars, cars that could create a “halo effect” around Chevrolet sports cars, especially the Corvette.

GM and Arkus-Duntov began their motorsport campaign in February 1956 taking three cars to compete in the Daytona Speedweeks events.

The team took three Corvettes; two of them pretty much stock production cars, and one modified to compete in the Modified Sports Car division.

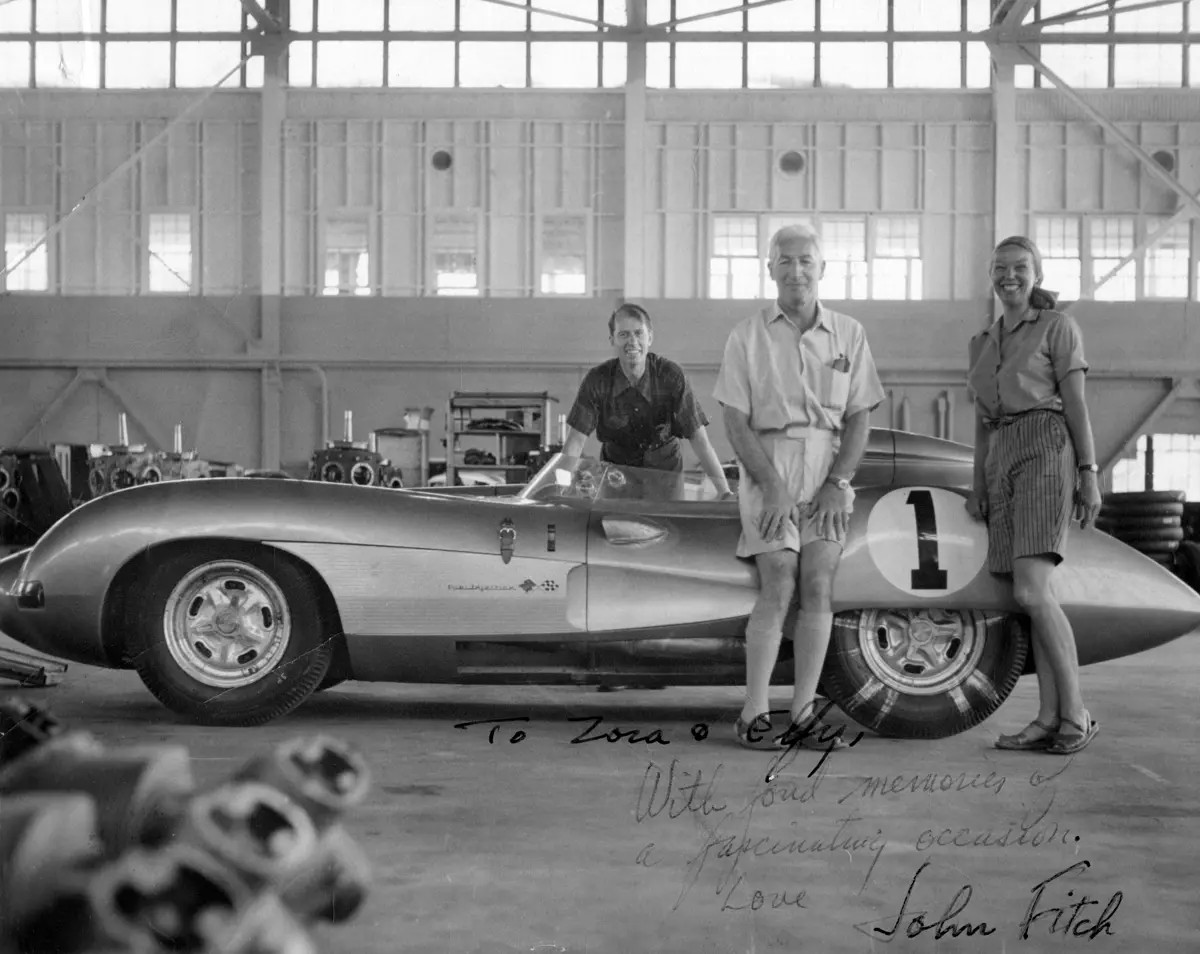

It proved to be a highly successful campaign. Driver John Fitch won the Sports Car division and lady driver Betty Skelton achieved a second place in another event, both of these victories going to stock Corvettes.

Arkus-Duntov fielded a modified Corvette in the Modified Sports Car division and won the event, proving to the onlookers, and to GM Chevrolet management, that the expertise was there to run successful motorsports campaigns.

The next stop was to be at the 12 Hours of Sebring: a race that would provide a reality check for GM Chevrolet.

The team for this event fielded four Corvettes with the sporting SR package, and one car fitted with a larger capacity engine.

Zora Arkus-Duntov declined to lead this team and so it fell to John Fitch to take on the role of Team Manager. John Fitch with co-driver Walt Hansgen managed a respectable ninth place enabling Chevrolet to feel well pleased with themselves. But this was also a bit of a “moment of truth” for Chevrolet’s leadership, especially for General Manager Ed Cole who watched the race and arrived at the inevitable conclusion that in order to be truly competitive they would have to create purpose built racing sports cars – would Chevrolet commit to doing this? The answer would, in the first instance, prove to be yes.

Project XP-64

Wisely it was decided not to try to re-invent the wheel but to learn as much as possible about the already successful competition cars being fielded by the Europeans.

To this end in 1956 a Jaguar D Type was obtained from racing driver Jack Ensley with the brief to convert it to left-hand-drive, to shoehorn a high performance Chevrolet V8 into it, and then to clothe it in American Chevrolet styling.

As with so many ideas that seem pretty good the team working on the Jaguar soon discovered that “Nothing is as easy as it looks” and they communicated that they couldn’t achieve the stated goal.

After a bit of an “Oh dear, how sad, never mind” moment the team leadership decided to try a different approach.

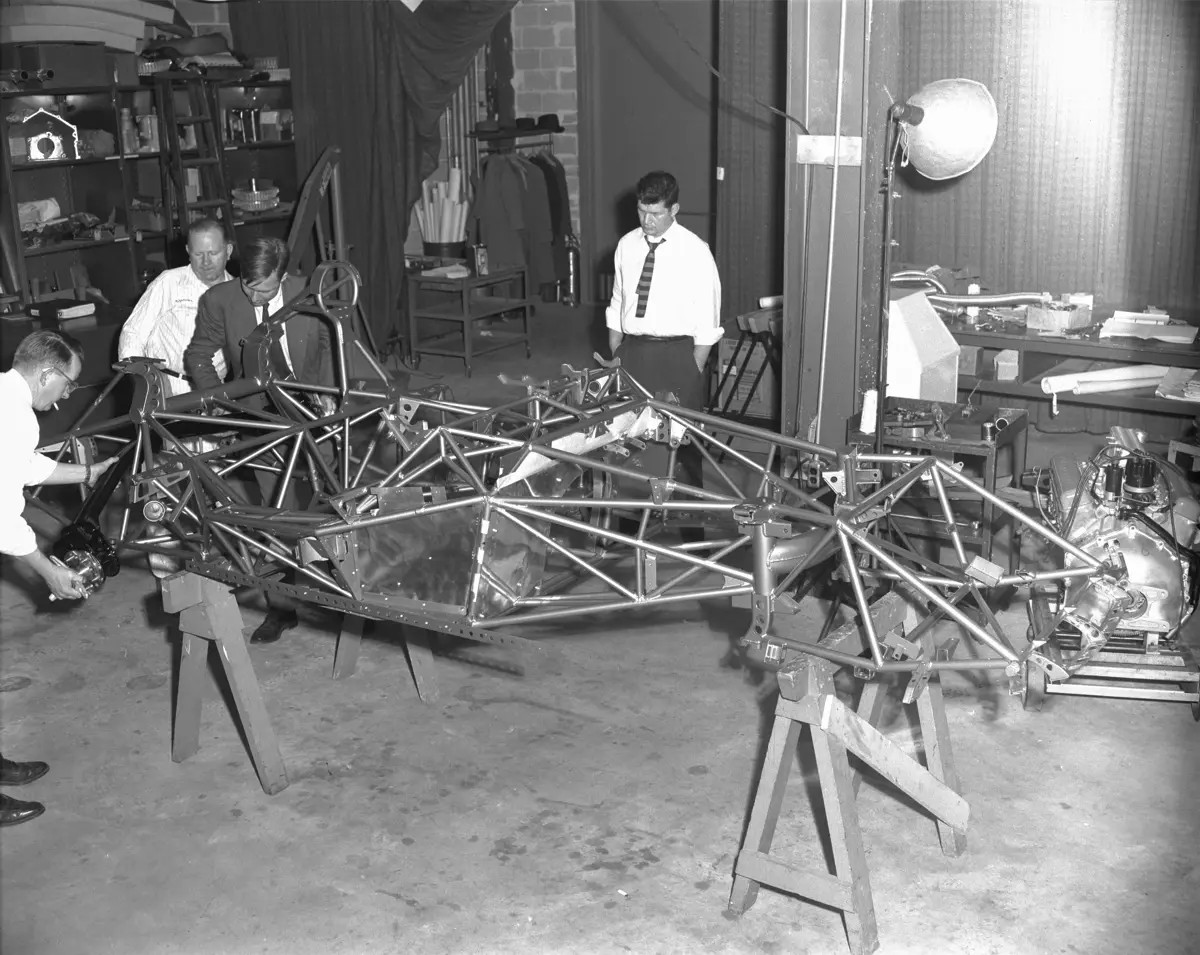

The new project was labelled XP-64 and in the interests of not re-inventing the wheel a new car to reverse engineer and modify was obtained. This was a nice Mercedes 300 SL and the guys set about separating the chassis from the body, lifting out the Mercedes engine, and installing a suitable Chevrolet V8.

This car was to become the development mule. Its tubular space frame chassis was the design concept basis for the second car – the purpose built racing sports car.

The team that began this project included Robert Cumberford and Anatole Lapine, with Clare MacKichan charged with creating the bodywork.

It was at this point in 1957 that Zora Arkus-Duntov was persuaded to take on the role of Chevrolet’s Director of High Performance Vehicles following on from his work on making the Corvette a true high-performance sports car, and in recognition of his expertise in motorsport competition which included a sound knowledge base in European racing sports cars.

He and his team were given their own space in the Chevrolet Engineering Center where they could work without distractions to achieve the goal set for them – to create a viable sports racing car that could compete with the best Europe could muster.

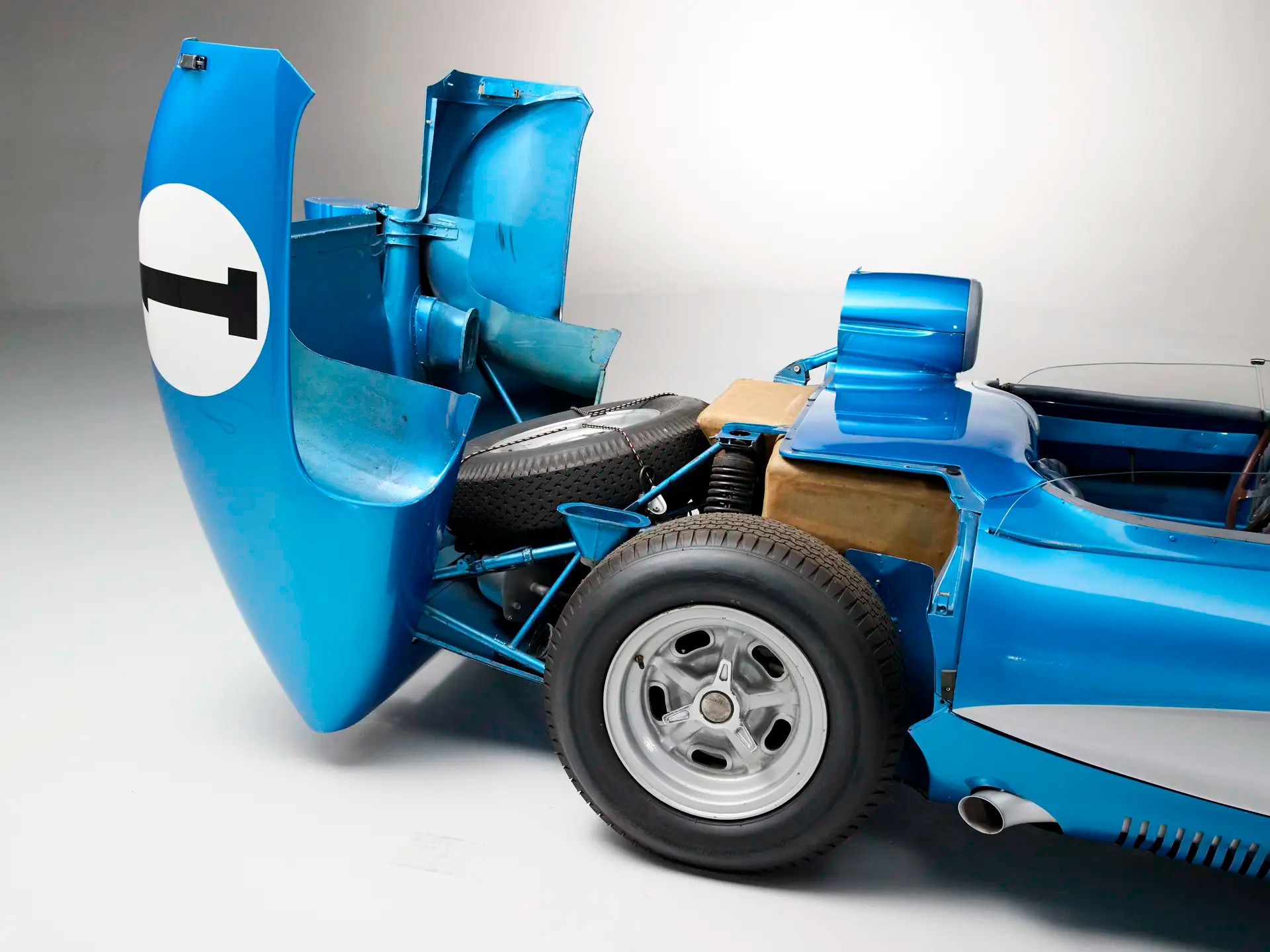

Two cars were created, the development mule based on the re-modeled Mercedes 300 SL, and the Corvette SS purpose built racing car which was built on a space frame chassis made of chrome-molybdenum steel tubing.

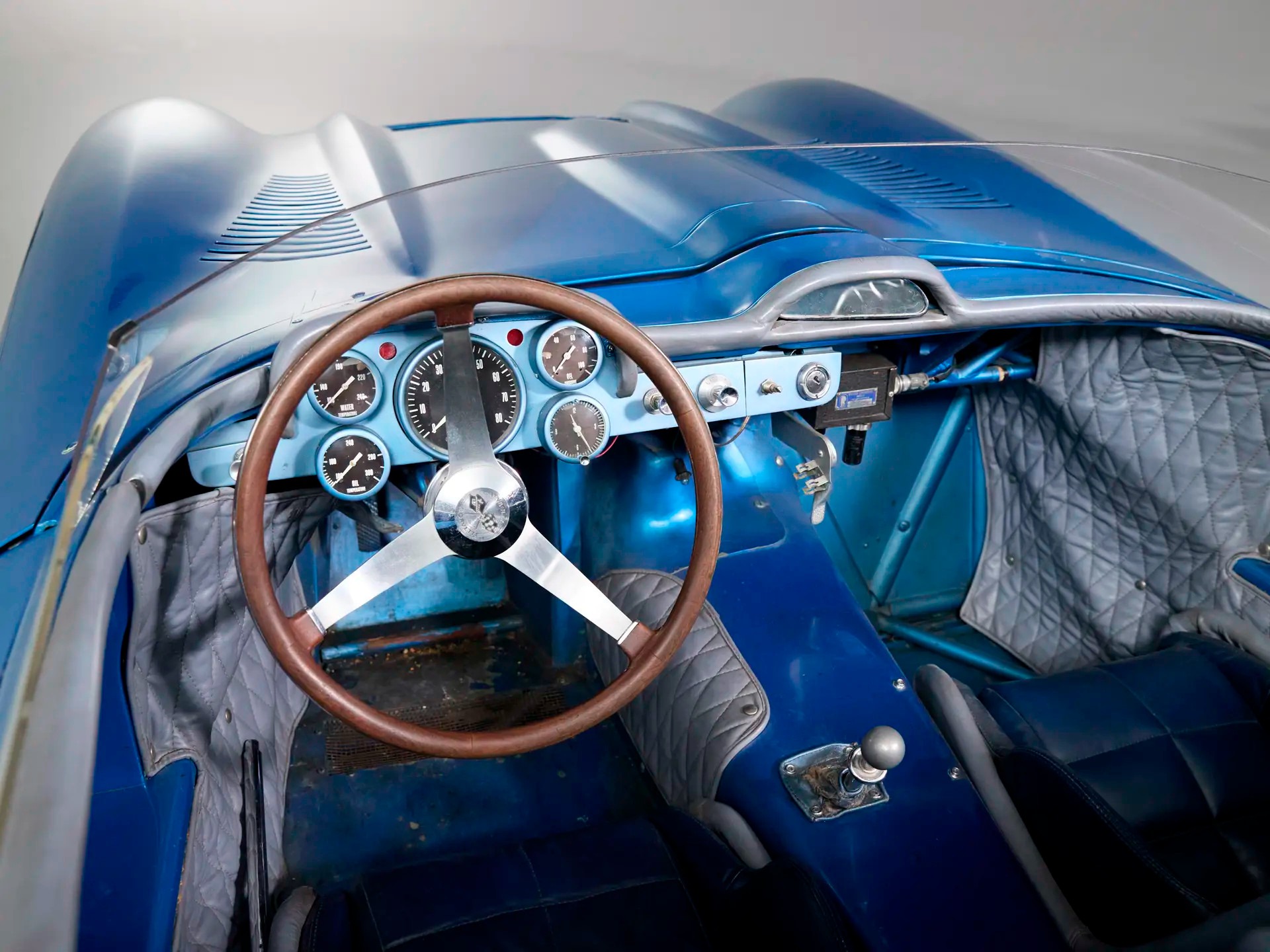

The front suspension was fully independent by short-long arms with coil springs and tubular shock absorbers, while at the rear Arkus-Duntov used a DeDion setup with four trailing arms, coil springs and tubular shocks. The steering was by a Saginaw recirculating ball system.

This was still a time in the United States in which disc brakes had not yet become popular and for the Corvette SS this resulted in its being fitted with drum brakes all around. These brakes featured a drilled steel inner drum, that drum then being wrapped in a finned aluminum outer drum to maximize cooling.

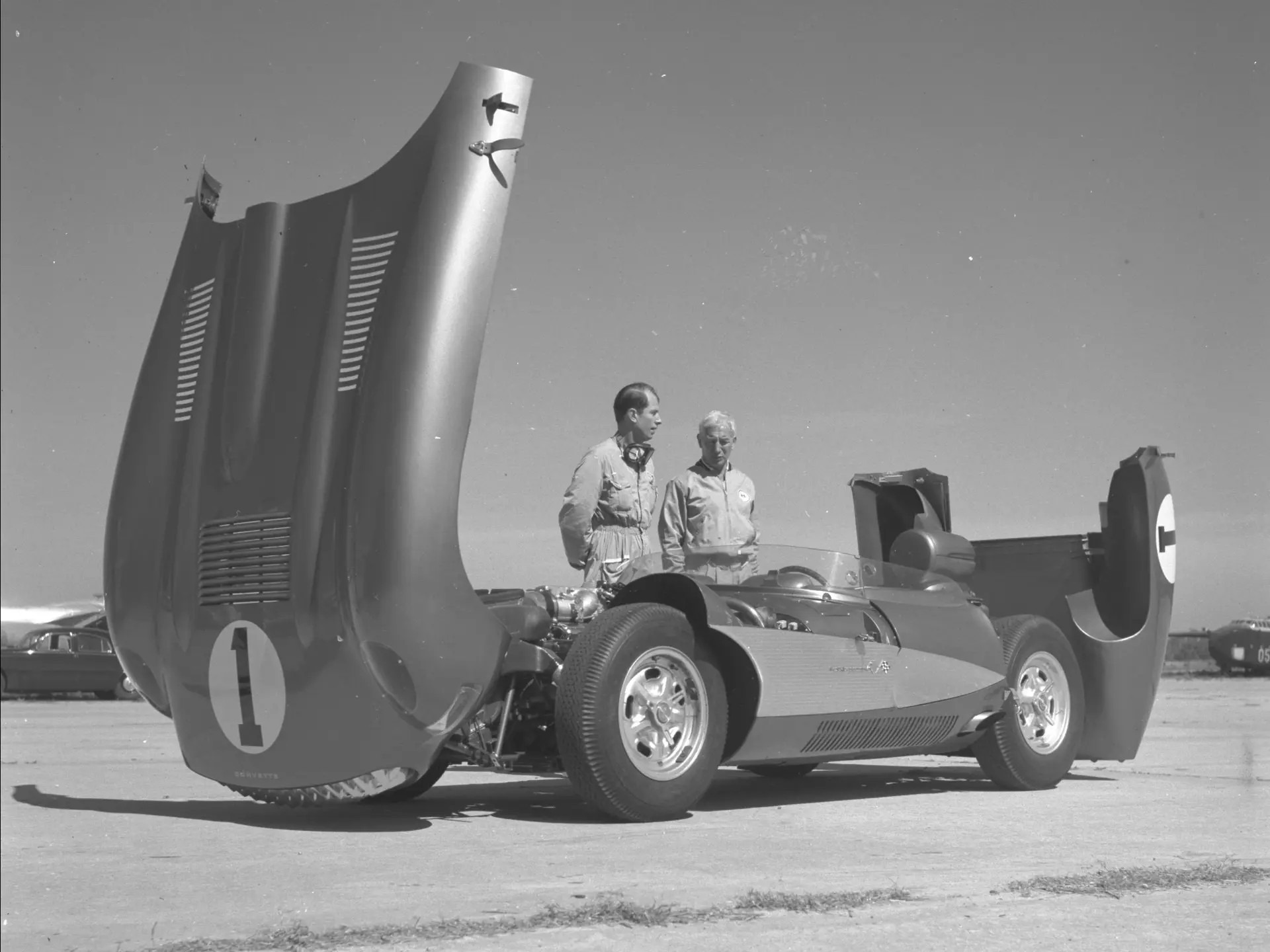

In the interests of keeping weight down to an absolute minimum the decision was not to make the bodywork of fiberglass, as had been done for the development mule, but instead to use magnesium alloy.

Magnesium alloy was challenging to work with but the bodywork was created by craftsmen of the Chevrolet styling Department who demonstrated they had the skills to meet the challenge.

The craftsmen of the Styling Department also created a bubble canopy to fit over the driver and passenger compartment. In practice this was not used as the magnesium alloy bodywork was so efficient at transmitting heat to the passenger compartment that it could not be comfortably used.

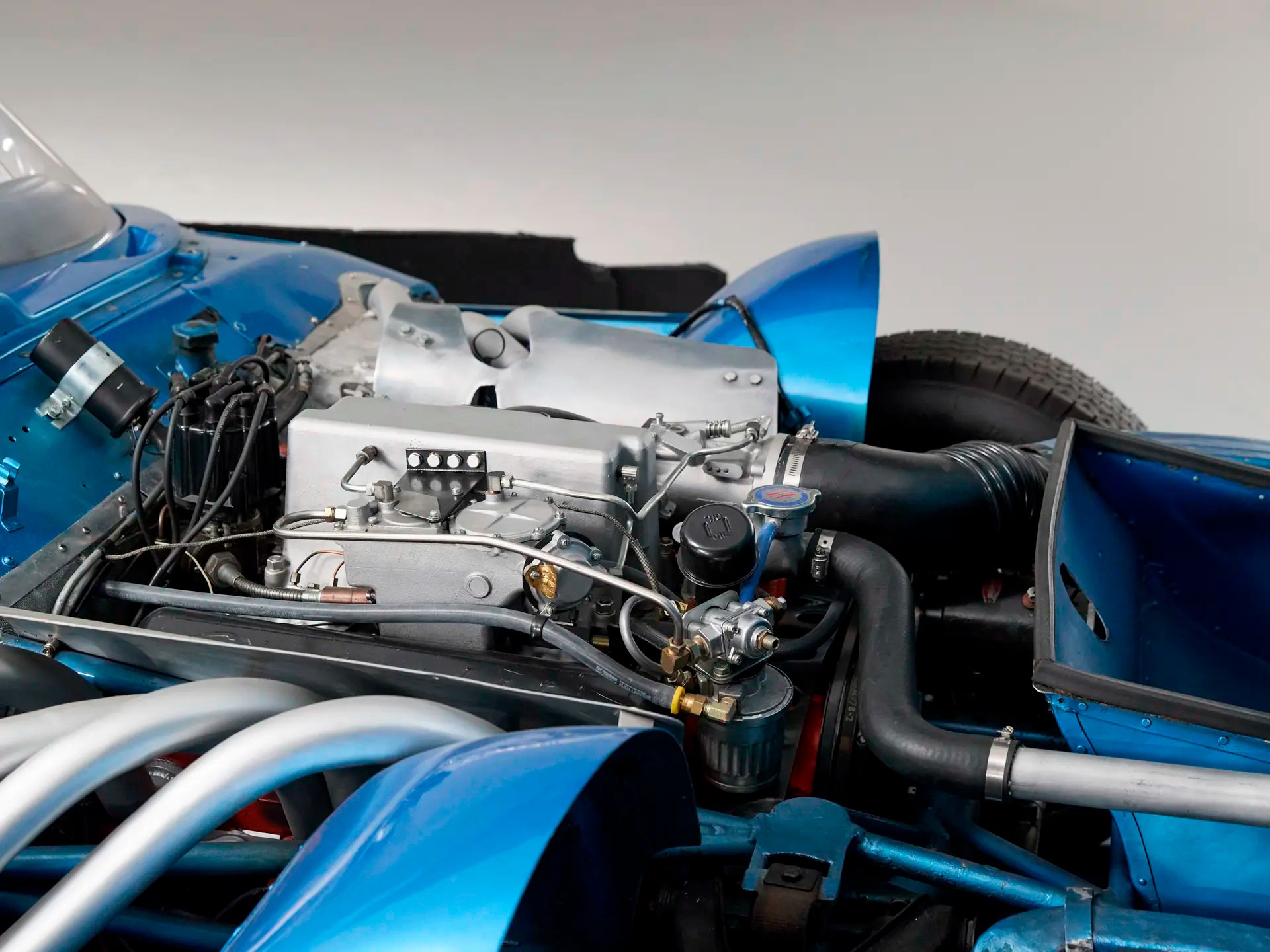

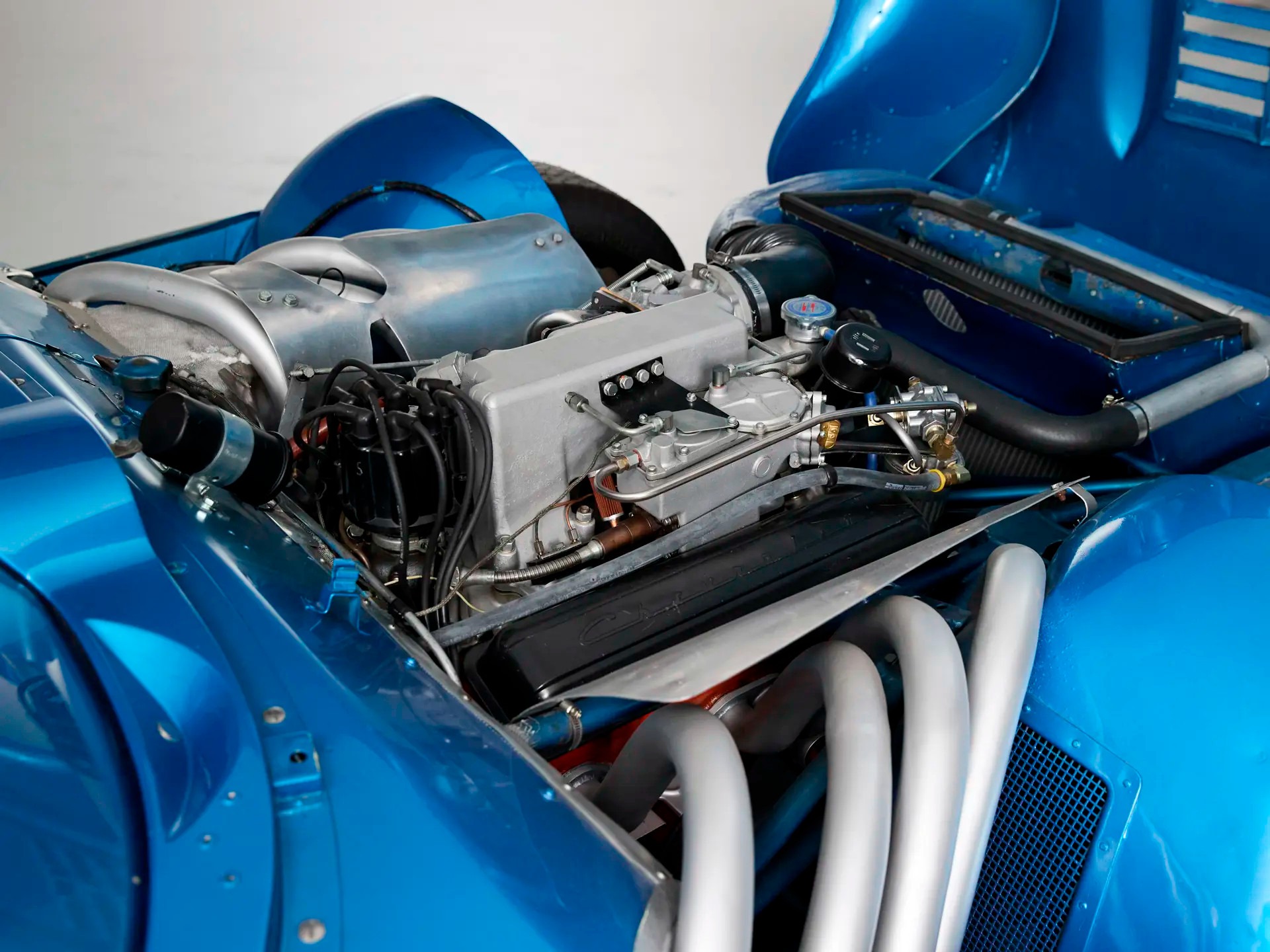

The engine used in the Corvette SS was a 283 cu. in. small block V8 with cylinder heads, solid valve lifters, water pump, radiator core and clutch housing all made of aluminum alloy, while the oil pan was made in magnesium.

The 283 cu. in. V8 was fed fuel via a Chevrolet Ramjet fuel injection system which had two fuel pumps. Fuel tank capacity was 43 US gallons (163 liters).

The engine sent its 300hp to the rear wheels via a four speed close ratio all synchromesh gearbox with aluminium housing. The differential housing was also made of aluminium alloy and featured a Halibrand quick-change system so the final drive ratio could be easily changed to suit the needs of the track the car was being raced on. The quick-change unit allowed the ratio to be changed in the range anywhere from 2.63:1 to 4.80:1.

The complete Corvette SS tipped the scales at 1,850lb dry weight, fully 1,000lb less than a production Corvette. The car represented a huge technological leap for Chevrolet.

It had taken a scant five months to create the Corvette SS, and it had not been created just to look pretty. Shoes are meant to be worn and the plan was for this car to take Chevrolet to the 24 Hours Le Mans. Its first proving race was planned to be the 12 Hours of Sebring in March 1957.

The car was not ready until a week before that race and did not arrive at the track until March 22, the day before the race, making preparation a tad hectic. Arkus-Duntov actually took both the development mule and the custom Corvette SS to Sebring, always good to have a spare if you can.

The development mule tends to get overlooked in the story of the Corvette SS but in fact the mule was a very competitive racing car in its own right.

At the track when the Friday practice was over Arkus-Duntov was approached by none other than Juan Manuel Fangio and Stirling Moss, who were interested in the car. Arkus-Duntov happily showed it to them and permitted each of them to take the development mule out for a bit of a run on the track.

Juan Manuel Fangio put down a lap time of 3’27” and Stirling Moss 3’28” – times which were 2.4″ and 2.3″ faster than the previous year’s winner, Mike Hawthorn driving a Jaguar D-Type.

The Corvette SS demonstrated its potential during the 12 Hours of Sebring race driven by John Fitch and Piero Taruffi, but was plagued with mechanical issues, particularly a failed ignition coil, and a failed suspension bushing that hadn’t been properly installed during the car’s preparation.

The car completed 23 laps before Arkus-Duntov opted to withdraw it: the Sebring race was not to be the main event but a practical trial. Having accomplished their test and evaluation it was time to take the car back to the works, fix the problems, and prepare the car for the main event, the 24 Hours Le Mans.

Life can be unpredictable. As Forest Gump says in the movie “Life is like a box of chocolates, you never know what you’re going to get”: and this was to happen to Zora Arkus-Duntov and the team that had created the Corvette SS with their eyes firmly fixed on Le Mans.

Work on perfecting the Corvette SS continued through April 1957 to address the technical issues and create the best possible Le Mans car Chevrolet could make. But the “expect it when you least expect it” moment came on June 6, 1957 when it was announced that The Automobile Manufacturers Association (AMA) had come to an agreement with all major car makers to end fully-supported car racing efforts.

Ironically the 1957 24 Hours Le Mans was won by Mike Hawthorn driving a Jaguar D-Type – the car that both Fangio and Moss had shown to be slower than the Corvette development mule in practice at Sebring. Thus demonstrating that if a Corvette SS had competed at Le Mans and successfully finished the race it could very well have snatched a victory for the United States and for Chevrolet, beating the Europeans at their own game.

As it turned out the honor of beating the Europeans, and especially Ferrari, would fall upon Ford and their GT40 a few years later.

As for the Corvette, a team of Corvettes campaigned by Briggs Cunningham went to the 24 Hours Le Mans in 1960 and although they were fairly stock cars the one driven by John Fitch and Bob Grossman managed eighth overall place and a class win.

The original Corvette SS as raced at Sebring sat neglected at Chevrolet for a while being occasionally used for promotional purposes. Zora Arkus-Duntov took the car to Daytona International Speedway in 1959 and demonstrated it with a lap speed of 155mph.

Subsequent to that he took the car to GM’s Mesa Proving Ground, and got it up to a top speed of 183mph, proving that he and his team had got it right.

It was in 1966 that Arkus-Duntov contacted Anton “Tony” Hulman Jr. of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway Museum suggesting that he contact Chief Engineer, A.C. Mair with a view to having the car donated to the museum. This proved successful and Arkus-Duntov was able to present the car to the Museum on May 29, 1967, at the Indianapolis 500 Driver’s Meeting during race week.

The Corvette SS in the intervening years has been displayed at a variety of special and significant events and is now coming up for sale for the first time.

The car is to be sold by RM Sotheby’s at their Miami 2025 sale to be held over February 27-28, 2025.

You will find the sale page for this unique and historic car if you click here.

Picture Credits: All historic photos courtesy GM Archives. All pictures in color of the sale Corvette SS courtesy RM Sotheby’s.

Jon Branch is the founder and senior editor of Revivaler and has written a significant number of articles for various publications including official Buying Guides for eBay, classic car articles for Hagerty, magazine articles for both the Australian Shooters Journal and the Australian Shooter, and he’s a long time contributor to Silodrome.

Jon has done radio, television, magazine and newspaper interviews on various issues, and has traveled extensively, having lived in Britain, Australia, China and Hong Kong. His travels have taken him to Indonesia, Israel, Italy, Japan and a number of other countries. He has studied the Japanese sword arts and has a long history of involvement in the shooting sports, which has included authoring submissions to government on various firearms related issues and assisting in the design and establishment of shooting ranges.