It is the road car you buy if you really wanted a racing car that you could drive on the road. It’s a car you could drive to the race track, defeat all comers, and then poodle home in.

This car is so pure bred race car in its design that it doesn’t have doors, and a windscreen and roof are optional extras.

The car in question is the Dallara Stradale, the only road car ever made by Dallara, a company that has dedicated its decades of engineering ingenuity to the creation of some of the greatest racing cars of all time: but unless you have a strong interest in racing cars you are likely to be unfamiliar with Dallara and the four wheeled projectiles they have created.

The Stradale emanates from the workshop of Dallara Automobili S.p.A. located in Varano de’ Melegari, Italy: the place the company began in back in 1972.

Dallara – A Potted History

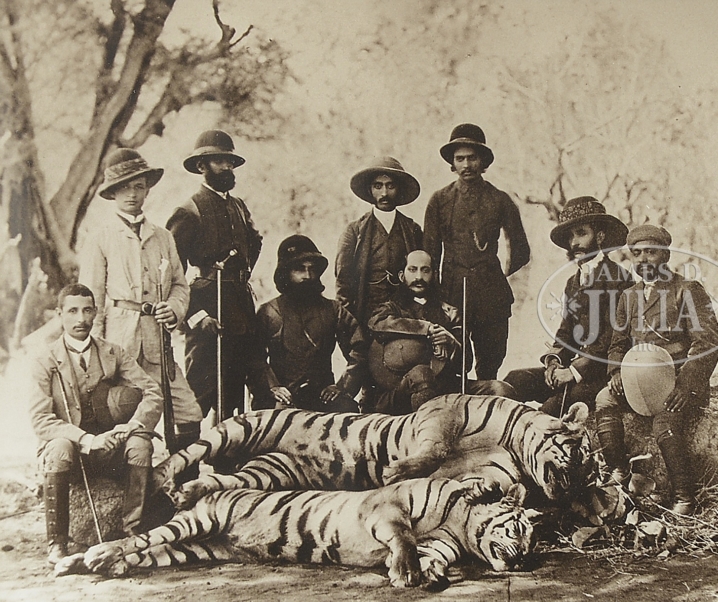

The founder was a man named Giampaolo Dallara, and his journey to become one of the most respected creators of racing cars began when he graduated from the Milan Polytechnic and went to work for Ferrari in 1960.

At Ferrari the young Giampaolo worked with Giulio Alfieri learning all he could, and then in 1962 he moved to Maserati where again he set himself to both contribute and to learn in the process of becoming a top designer.

In 1963 Giampaolo Dallara was recruited to Lamborghini, which was still a new manufacturer back then. Dallara was recruited to be chief designer working with engineers Paolo Stanzani, and Bob Wallace.

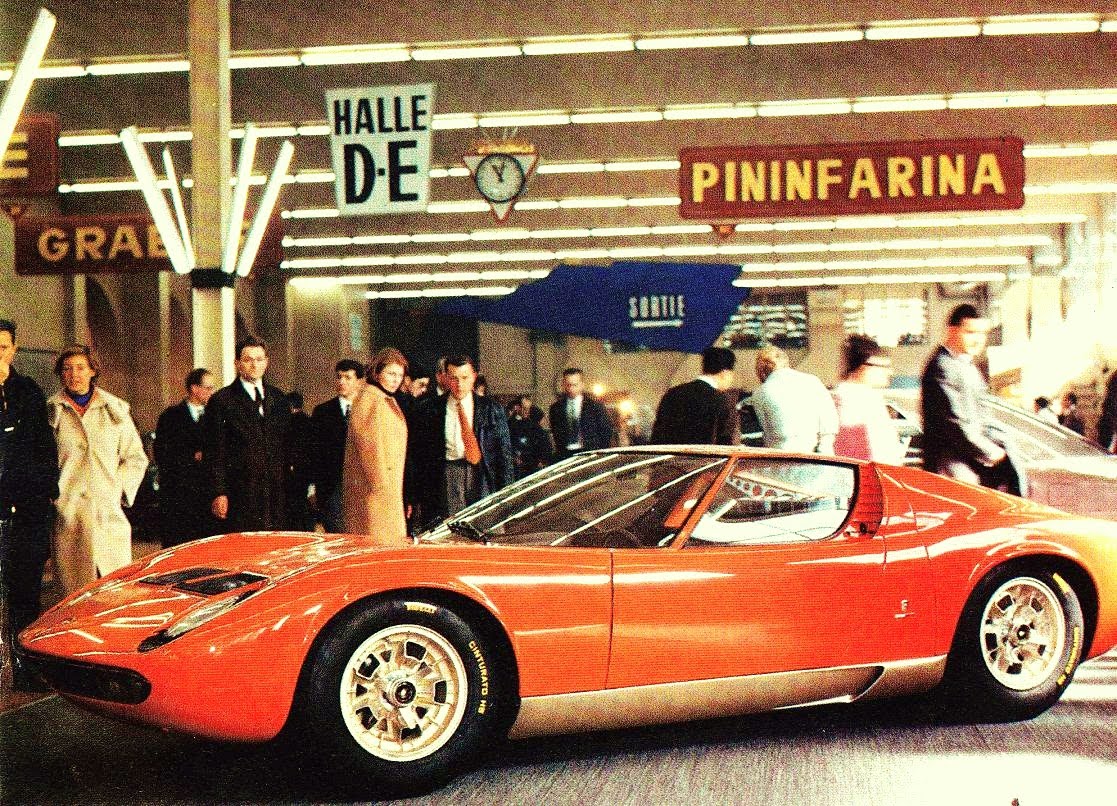

The two engineers had a project they wanted to work on which Ferruccio Lamborghini was not interested in. It was for a two seater GT car with a mid-engine, but Lamborghini had told them they could only work on it in their own time, and they had agreed to that. Young Giampaolo was also enthusiastic about this and agreed to join them.

The car they built between them was a rear mid-transverse engine equipped two seater GT fitted with Giotto Bizzarrini’s V12 engine. The rolling chassis was shown at the Turin Motor Salon in 1965 and even though it didn’t have a body or a name yet there were a surprising number of orders that came in during the show.

This was enough to convince Ferruccio Lamborghini to go ahead and build the car so he commissioned Marcello Gandini of Bertone to create the bodywork and interior, and the Lamborghini Miura came into existence to steal the hearts and minds of car enthusiasts all over the world.

Giampaolo Dallara left Lamborghini in 1969 and went to work for De Tomaso to pursue his primary interest in racing car chassis. While there he created a Formula 2 racing car that used a novel method of construction: and this proved to be so successful that De Tomaso used principles from the design to create their own Formula 1 car.

Despite his success Dallara had a desire to start his own company and in 1972 he did, specializing in racing cars.

Dallara called his fledgling company Dallara Automobili da Competizione and set about seeking clients to build racing cars for.

There are similarities between Colin Chapman’s story and the beginnings of Britain’s Lotus Cars, and the early history of Dallara cars. The Dallara company very much worked around a foundational principle of making cars as light as possible – in the same way as Colin Chapman’s famous mantra was “Simplify and then add lightness”.

Dallara worked on competitive cars for hillclimb and sports car racing, and then in 1973 was invited to be a consultant for the new Williams Formula 1 car.

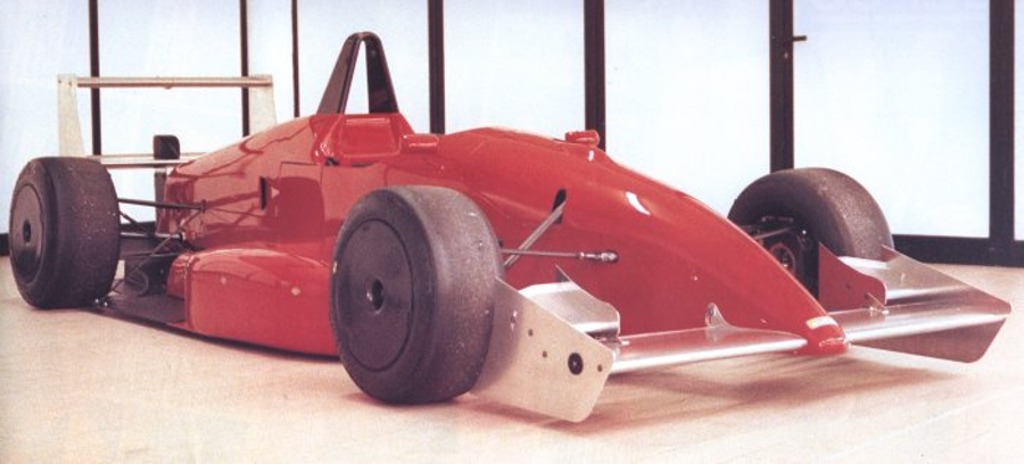

Dallara’s involvement in Formula 1 continued when they became the constructor for the BMS Scuderia Italia Formula 1 racing team from 1988-1992: and then in 1999 they were commissioned by Honda to create a Formula 1 chassis for evaluation as Honda were considering a return to Formula 1.

The thing that gave Dallara the greatest success however were his Formula 3 designs.

Dallara began creating Formula 3 chassis in 1981 and achieved near dominance in Formula 3 by 1993 with their Dallara F393 chassis (i.e. Formula 3 of 1993).

You can find a quite comprehensive history of Dallara’s involvement in Formula 3 on the F3 History website.

In 1997 Dallara decided to try their hand in the United States with a venture into the V8 drama filled sport of Indy Car racing and his first car was the Dallara IR-7, which was subsequently updated to the IR-8 and IR-9.

Success was near immediate with an Indianapolis 500 win for Eddie Cheever in a V8 Oldsmobile powered IR-7 in 1998, and another win in 1999 for an IR-9 driven by Kenny Bräck. It looked like Dallara had hit pay-dirt in Indy Car racing.

Dallara continued in research and development producing their second generation Indy car the IR-00 in 2000, and then the IR-02, followed by the IR-03 and IR-05 models built as carbon fiber monocoque body/chassis and equipped with double-wishbone pull-rod-actuated suspension.

The rest is history and Dallara became a dominant force in Indy Car and Champ Car competition, and maintained its popularity when those two separate competition series joined back together in 2008.

To catch a glimpse of Dallara technology in action here is a video of Gary Hauser in a Dallara GP2 car competing in a Hillclimb competition at Course de côte de St. Ursanne – Les Rangiers in 2013.

The Dallara Stradale

Giampaolo Dallara had a desire to build a road car of his own throughout his life, just as Carroll Shelby did when he and his staff created the Shelby Series I: but the pressures of not just making a living but of ensuring his company prospered effectively prevented Dallara from expending the considerable energy and finance into such a project.

So it was not until 2015, when Giampaolo was seventy nine years old, that work began on Dallara’s only road car.

The initial work of designing the car was done by a small company called Granstudio which had been founded by an ex Pininfarina designer.

Dallara’s philosophy was, like Colin Chapman’s, to “simplify and then add lightness” and so the decision was made to simplify the doors into non-existence and in that one fell swoop eliminate the weight doors would impose, and the weight of the reinforcing of the chassis/body to support them and the mechanisms to operate them.

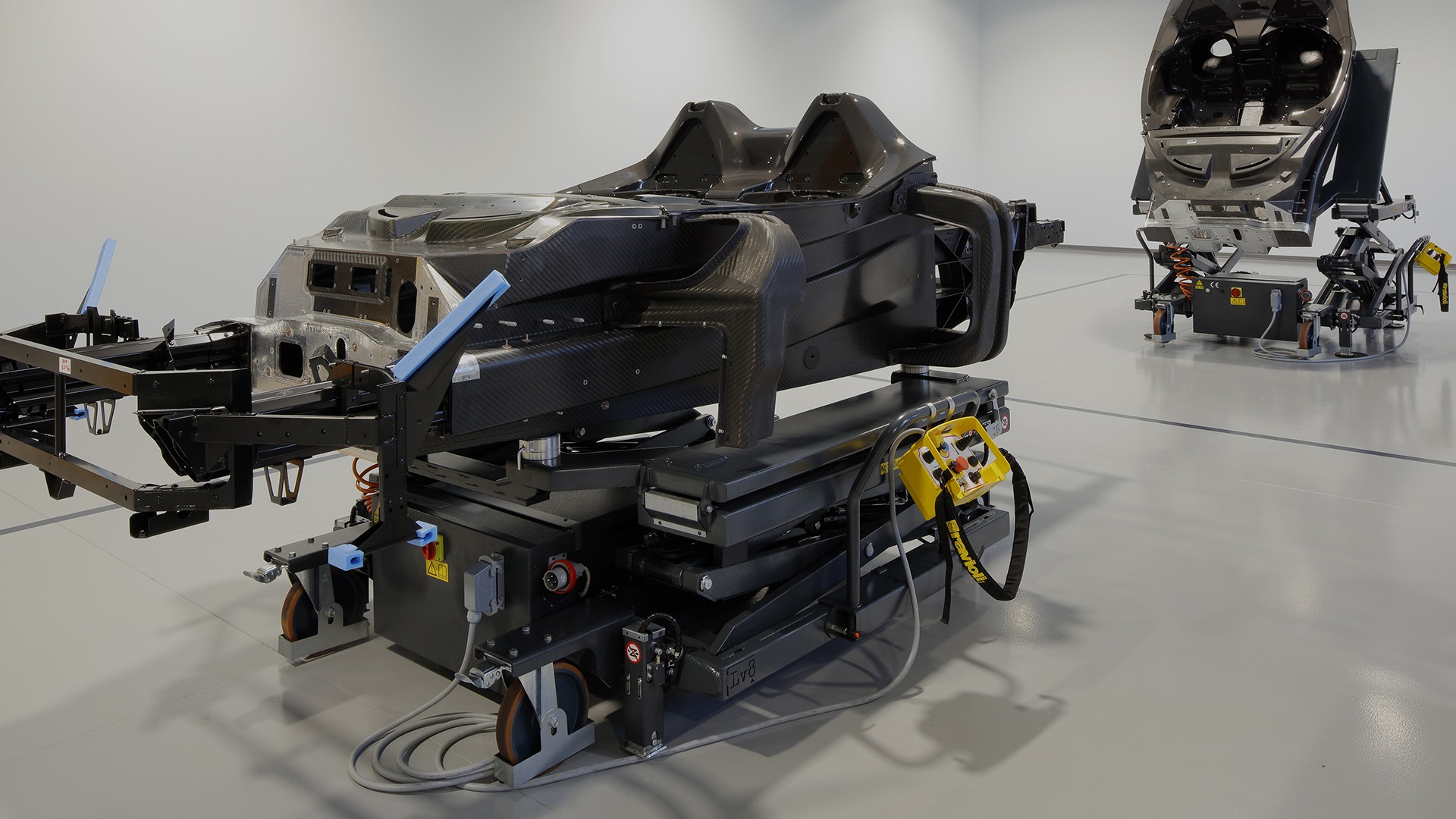

Dallara used a pre-peg autoclave process with hot compression moulding to make the carbon fibre components, ensuring maximum consistency, safety, strength, lightness, and stiffness.

This meant that the Stradale would have a strong uncompromised hollow carbon fibre tub with carbon fibre side structures to channel air into the engine compartment: one side sending air into the engine compartment and the other side sending air to the air-to-air intercooler.

The central chassis tub has aluminium structures incorporated into it front and rear with the suspension being by upper and lower wishbones with geometry set up for optimal tyre contact with the road. The front suspension is attached directly to the central tub.

Combined with the large tyres the Stradale is made to manage Italian secondary roads efficiently and so it can cope with rough surfaces, and even the occasional pothole if needs be – although one needs to remember that it is a high performance ultra light sports car and not a “built like a tank” four wheel drive: its made of carbon fibre and aluminium alloy – not Kryptonite.

The suspension has two modes: road, and track, with the track mode lowering the car and stiffening the suspension. Suffice to say track mode is for use on the track and not on secondary roads where lumps, bumps and corrugations may be encountered.

Dallara has a very sophisticated computer simulation setup at their headquarters and, just as with their racing cars, the Stradale design concepts were developed using computer simulations to refine the design of the body and suspension before the first prototype car was built.

The guidance for this road going guided missile is by rack and pinion steering and is very much as used in racing cars, complimented with electric power assistance.

The aerodynamics of the Stradale have been created to optimize both its ability to slip through the air with minimum resistance, and to ensure it presses down on the road as speed increases to make sure it is stable at speed and can exceed 1g of cornering force. In fact the Stradale can manage up to 2g cornering forces which opens up a whole different world when it comes to driving technique and experience.

Suffice to say the Stradale is the product of meticulous study in the wind-tunnel and computer modelling. This is a car for which styling has taken a back seat to practicality and performance. Great attention has been lavished on perfecting the cars aerodynamic performance.

Dallara has not just shaped the aerodynamic flow of air over the car, but also through the car. So vents in the top of the bonnet/hood area channel air to the large side ducts – made possible because the car does not have doors so the airflow can be much better controlled.

With the optional rear wing fitted the Stradale can be configured to deliver a jaw dropping 1,808 lb of downforce in coupe form: which is almost as much as the car’s dry weight, which is only 1,885 lb (855 kg).

This is in part made possible by the rear wing but also by the use of a splitter at the front and diffuser at the rear. If the rear wing is not fitted then the front needs to be fitted with reverse Gurney flaps to reduce the downforce and maintain an appropriate aerodynamic balance.

The aerodynamics of this car basically mean that the faster the driver is going – up to a point – the faster the car can corner, and the more stable it becomes. There is of course a limit, but that limit is so high up the cornering scale that the driver is going to have knuckles that turn a whiter shade of pale. Its a little research project to be reserved for a race track so that if you do succeed in coming unstuck you will have a safe place to absorb your loss of control without shattering any expensive carbon fibre.

If you have the opportunity to push this car to near its limits it is of course best approached in sensible incremental stages, and preferably under the guidance of a professional instructor, so you find its limits safely and can back off before incurring upsetting and expensive consequences.

The Stradale in its most basic form is sold with no windscreen or top. So unless you were buying it purely for track use you would certainly want to have the optional fittings to make it weatherproof so it can be comfortably used in rain, hail sleet or snow, and in hot summer sunshine – air-conditioning is available as an option.

The first of the optional body parts is a windscreen, made of racing polycarbonate glass, which transforms the car from an open Barchetta to an open Roadster. The second is a “T” piece which fits from the windscreen to the rear of the passenger compartment, turning the car into a “Targa”. The third components are the gull-wing doors. These fit to the “T” piece converting the car into a coupe.

The final optional extra is the rear wing which can be adjusted to deliver high levels of down-force for high speed handling and stability.

The power unit for this lightweight aerodynamic little fun missile is a tried and true Ford EcoBoost four cylinder mounted as a transverse rear-mid-engine and mated to either a conventional manual six speed gearbox with gear lever or an automated six speed with paddle shifters.

This Ford engine is a turbocharged 2.3 litre (2,261 cc) four cylinder DOHC with four valves per cylinder, equipped with Bosch electronics, and generating 395 bhp (400 PS). The Stradale engine has had significant internal refining so it delivers a tad more power than the Ford Focus RS which is built around the same base engine.

Despite the power sounding a bit less impressive than the rather higher figures one would expect in a car from McLaren for example, its important to remember that the Stradale is very light and nimble so that turbocharged four cylinder is able to propel it from standing to 100 km/hr mph in 3.3 seconds and attain a top speed of 280 km/hr (174 mph).

Brakes are steel ventilated discs all around with ABS and are capable of pulling the car up from 100 km/hr to stopped in 31 metres: that is enough braking ferocity that you might fear your eyeballs are going to bump into the inside of your Ray Bans and leave wet squishy marks there.

The interior of the car is Spartan minimalist with beautifully crafted carbon fibre, and leather on the seats. Getting in requires a bit of athletic prowess: by each seat is a place to put your foot on marked “Step Here” in nice friendly letters. So you step on that and then maneuver your other leg in and your body onto the seat.

The steering wheel hosts the main controls so the driver doesn’t need to take his hands, complete with white knuckles, off the wheel. This is particularly true of the paddle-shift equipped cars whereas those with the old fashioned style gear lever of course require dropping a hand onto the short throw gear lever.

Luggage carrying capacity is not the Stradale’s strong suit. It has two luggage containers in the rear, and provides crash helmet size compartments in the rear of the passenger compartment, but there’s only space for soft luggage which can be compressed into relatively small compartments.

That being said, for the driver who is traveling alone there would be plenty of room on the passenger seat to stash soft luggage for a long trip.

Conclusion

The Dallara Stradale seems to be a car that was created not for the purpose of making a monetary profit, but purely for the love of doing it. Dallara has said they will only make up to 600 of them, and as I understand it they have so far made less than 100.

Because the Stradale was not made with marketing in mind it is one of the most pure-bred GT cars ever made. Colin Chapman of Lotus would have absolutely loved it I think.

Its a car that was made possible because of Dallara’s investment in developing racing car chassis and Giampaolo Dallara’s desire to fulfil his wish to make one road going sports car that incorporated his company’s expertise, learned over decades, into the most desirable driver’s car possible.

Without doubt Giampaolo Dallara’s team has succeeded and should be congratulated on this achievement. What they’ve accomplished is very special. Its not a car for everyone – but for those with a passion for driving, and for cars that are inherently things of beauty. Interestingly despite the fact that the designers of the Stradale were not necessarily trying to create a thing of beauty they managed it anyway, I think this reflects the passion that went into creating this extraordinary car.

Technical Specifications

Body: Carbon Fibre/aluminium monocoque. 2 seat body convertible to Barchetta, roadster, Targa, and coupe body styles. Optional body components: Windscreen made of racing polycarbonate glass, central “T” piece, gull-wing doors/coupe top assemblies, rear aerodynamic wing.

Dimensions

Length: 4,185 mm (164.76 in.)

Width: 1,875 mm (73.82 in.)

Wheelbase: 2,475 mm (97.44 in.)

Track: Front 1,651 mm (65 in.), Rear 1,590 mm (62.6 in.)

Height: 1,041 mm (40.98 in.)

Weight: 855 kg (1884.95 lbs.) Dry.

Engine: 2,261 cc (137.97 cu. in.) inline four cylinder DOHC Ford turbocharged engine with Bosch electronic system and direct fuel injection. Power 400 PS (395 hp) @ 6,200 rpm. Torque 500 Nm (368.78 lb/ft) @ 3,000-5,000 rpm. 4 valves per cylinder. Maximum engine speed 6,500 rpm. Engine mounted as transverse rear-mid-engine driving the rear wheels.

Transmission: Six speed manual gearbox with traditional gearlever or six speed automated sequential manual gearbox with paddle shift.

Suspension: Upper and lower wishbones to all four wheels.

Steering: Rack and pinion with electric assist.

Tyres: Front: 205/40/18. Rear: 255/30/19.

Brakes: Front: 305 mm steel slotted ventilated discs with 4 piston fixed calipers. Rear: steel ventilated and slotted steel discs. ABS system. Brake performance 100 km/hr to stopped in 31 metres.

Performance: Top Speed 280 km/hr (174 mph). Standing to 100 km/hr (60 mph) 3.3 seconds. Standing to 100 mph 8.1 seconds. Standing quarter mile 11.5 seconds.

Fuel Economy (Approximate): Metric: Combined 9.4 l/100 km. City 10.2 l/100 km. Highway 8.1 l/100 km.

US mpg: Combined 25 mpg, City 23 mpg, Highway 29 mpg.

Jon Branch is the founder and senior editor of Revivaler and has written a significant number of articles for various publications including official Buying Guides for eBay, classic car articles for Hagerty, magazine articles for both the Australian Shooters Journal and the Australian Shooter, and he’s a long time contributor to Silodrome.

Jon has done radio, television, magazine and newspaper interviews on various issues, and has traveled extensively, having lived in Britain, Australia, China and Hong Kong. His travels have taken him to Indonesia, Israel, Italy, Japan and a number of other countries. He has studied the Japanese sword arts and has a long history of involvement in the shooting sports, which has included authoring submissions to government on various firearms related issues and assisting in the design and establishment of shooting ranges.