In mainland China there is a saying “Done is better than perfect”. It is an attitude that tends to be reflected in the quality of typical Chinese made goods; the price may be low but the quality control is commonly lacking. The Japanese have a long tradition of a different attitude to quality which might best be summed up as “It’s not done until it’s perfect”. A Japanese friend once said to me that for a Japanese it is not just the things that are visible that are important, the things that are invisible, the things that no-one will actually notice are just as important. A commonly used example of the Japanese fixation with quality is the Japanese sword. Around the year 1000AD a sword smith somewhere decided that a gently curved single cutting edge sword that could be wielded with two hands would be the most efficient weapon and so the Japanese sabre was born. And whilst in China a variety of sword designs of varying efficiency and quality were produced the Japanese fixed on perfecting one, and perfect it they did, focusing not just on that which was visible, but on that which was invisible. The invisible things included the types of steel alloy being combined, folding to create a laminated steel that is not visible like a Damascus blade, and the process of differential hardening to produce a blade that can keep a razor edge yet survive being struck against a helmet, armor or another blade. The Japanese “Katana” is filled with subtlety and hidden technologies and one should never imagine that one can assess the Japanese sword by buying a Chinese made imitation and “testing” that, as we sometimes see on TV shows. No-one is likely to 3D print a Japanese Nihonto any time soon, if ever. Similarly to appreciate the Nihonto one needs to train under a teacher who understands the art of drawing and cutting with the sword, one who has attained mastery. The capabilities of the Japanese sword do not become apparent unless combined with a mastery of the art of the sword. Finding a suitable teacher outside of Japan can be a challenge but there are some. For those in New York there is a good club that can be found here. For those elsewhere visit this link and see what you can find. If you are interested in DVD’s, Japanese sharpening stones and other equipment then Nihonzashi is a good place to start looking.

When it comes to Japanese kitchen knives we sometimes find people wanting to compare the Japanese knives to the “Samurai sword” and whilst its true that some of the technology is shared the reality is that a sword and a kitchen knife are used in a totally different way for rather different purposes. Yes, it can be argued that both the sword and the kitchen knife are designed for cutting up prime meat, and indeed in my house we have a tradition of carving the Christmas turkey with a katana, but that’s where the similarity ends. Carving a turkey with a katana is actually a bit awkward. It’s razor sharp and it slices well, but the blade profile is not really the best for turkey carving and the blade is much too thick. So we expect somewhat different techniques for making a hand made Japanese knife for a chef compared with a sword made for carving up prime meat and bone in more difficult circumstances.

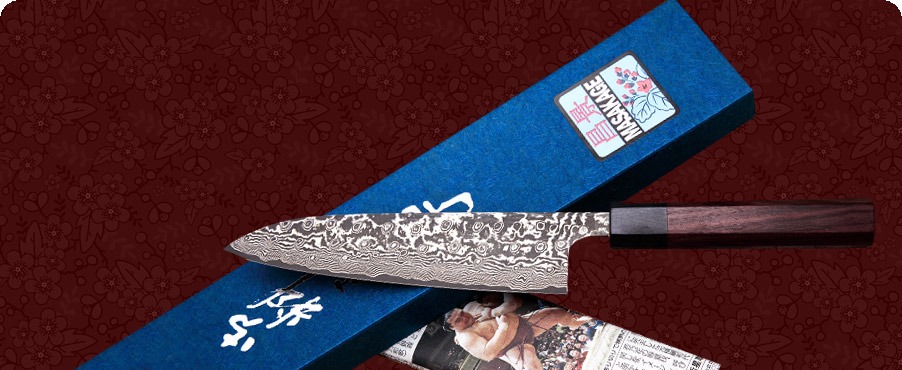

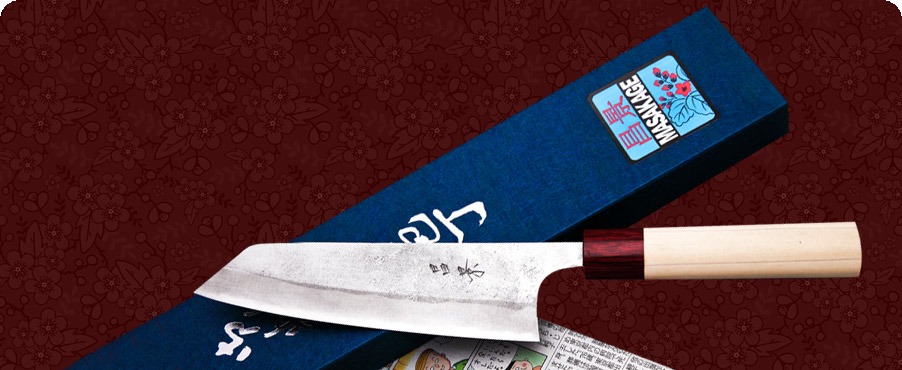

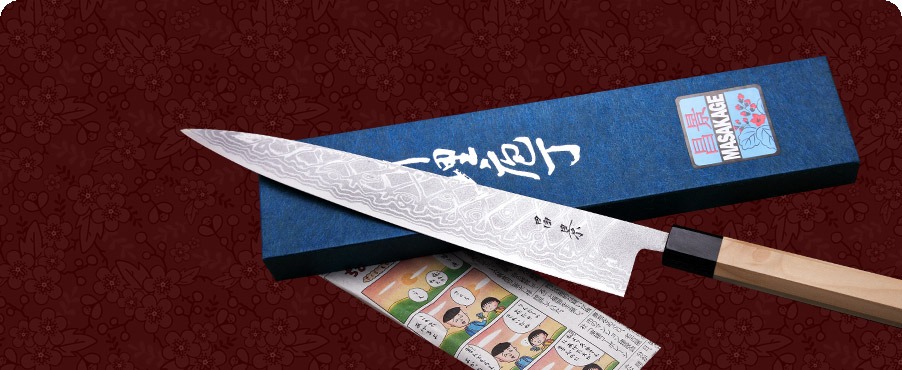

Masakage is one Japanese small producer of hand made chef’s knives. Each knife has that inestimable quality of being hand made and therefore just a little bit unique and personal. There are three master blacksmiths at Masakage, Hiroshi Kato, Katsushige Anryu, and Yu Kurosaki, and one master knife sharpener Takayuki Shibata. Knives are made in a variety of styles to suit different tastes in aesthetics. These knives are things that you are likely to keep and pass on to your next generation. Conversation pieces that help define your kitchen. Masakage describe their knives as “knives to fall in love with”. I personally really like the understated elegance of the Hikari collection, which have you fallen in love with?

(All pictures courtesy of masakageknives.com)

Jon Branch is the founder and senior editor of Revivaler and has written a significant number of articles for various publications including official Buying Guides for eBay, classic car articles for Hagerty, magazine articles for both the Australian Shooters Journal and the Australian Shooter, and he’s a long time contributor to Silodrome.

Jon has done radio, television, magazine and newspaper interviews on various issues, and has traveled extensively, having lived in Britain, Australia, China and Hong Kong. His travels have taken him to Indonesia, Israel, Italy, Japan and a number of other countries. He has studied the Japanese sword arts and has a long history of involvement in the shooting sports, which has included authoring submissions to government on various firearms related issues and assisting in the design and establishment of shooting ranges.