In the period after the American Civil War the situation in Europe was changing rapidly with the unification of the German States into a united country which also marked a period of the rapid industrialization in Germany and by the 1890’s the building of the German Navy as a force to be equal to the British Navy. People in the British colonies of Canada and Australia both grew concerned about the shifts in the balance of power and in that time period began to realize that depending on Britain for their protection was simply not trustworthy. Canada moved first in deciding they needed to establish arms manufacturing in Canada and in the 1890’s sought licensing from the British Small Arms Company to manufacture the Lee-Enfield rifle in Canada. The Birmingham Small Arms Company said no but were also unable to sell Lee-Enfield rifles to Canada as production was being fully used providing rifles for the Boer War in South Africa.

The Canadian government seemed to be in a bit of a bind but there was already a gentleman who had come to Canada in 1897 and who had his own proprietary rifle design and that was Sir Charles Ross. Sir Charles Ross had been a lieutenant in the 3rd Battalion, the Seaforth Highlanders and had served in the Second Boer War. He had designed his straight pull rifle and had some made which were used by his light machine gun battery during the Second Boer War successfully. So when he presented his rifle to the Canadian Government as an alternative to the Lee-Enfield his rifle had already seen active service albeit in very limited numbers.

The Canadian Government agreed to Ross setting up an arms factory in Quebec City which he did in 1903. He was contracted to make and supply rifles but as he was in the process of setting up his factory the first Mark I rifles were assembled at the Quebec City factory using parts actually made by American manufacturers Billings & Spencer and also the Frank Mossberg Company (which was a different company to the O.F. Mossberg company). The first order of 1,000 rifle went to the Royal Northwest Mounted Police in 1905 who promptly found the rifles to have a great many defects most notably a bolt stop that was so poorly designed that it allowed the bolt to fall out of the rifle, and springs which were badly tempered. The Royal Northwest Mounted Police went back to using their tried and true 1894 Winchesters and Lee-Metford rifles having rejected the first model Ross rifles in 1906.

Sir Charles Ross modified these early Mark I rifles to correct the faults as he got his factory under way and the new model was the Mark II of 1905. The Mark II action was further refined so it could not only handle the .303 British service rifle cartridge but also Ross’s .280 Ross cartridge which offered much higher performance and which became very highly regarded as a sporting round. Not only did Sir Charles Ross create his .280 Ross which was capable of sending its 7mm projectile downrange at 3,000fps but he also developed a .354 Ross-Eley which did not enter full production.

Ross continued to work on improvement of his rifle and there were numerous changes made on the road to the creation of the next model the Mark III of 1910 otherwise known as the Model 10. It would be the Mark III that would become the service rifle for Canadian troops heading off to France to fight in the First World War. No doubt as Ross created his improvements to the Mark II Ross he could not foresee the conditions that his rifles were about to be subjected to in the mud and crud of the Western Front. The new multi lug bolt locking system no doubt looked to be a worthwhile advance over the simple Mauser like twin locking lugs of the Mark II. But whilst the “improvements” looked good in theory and actually created a rifle that would prove to be excellent in one particular role, yet they did not make it more dirt resistant and that would prove to be a major flaw.

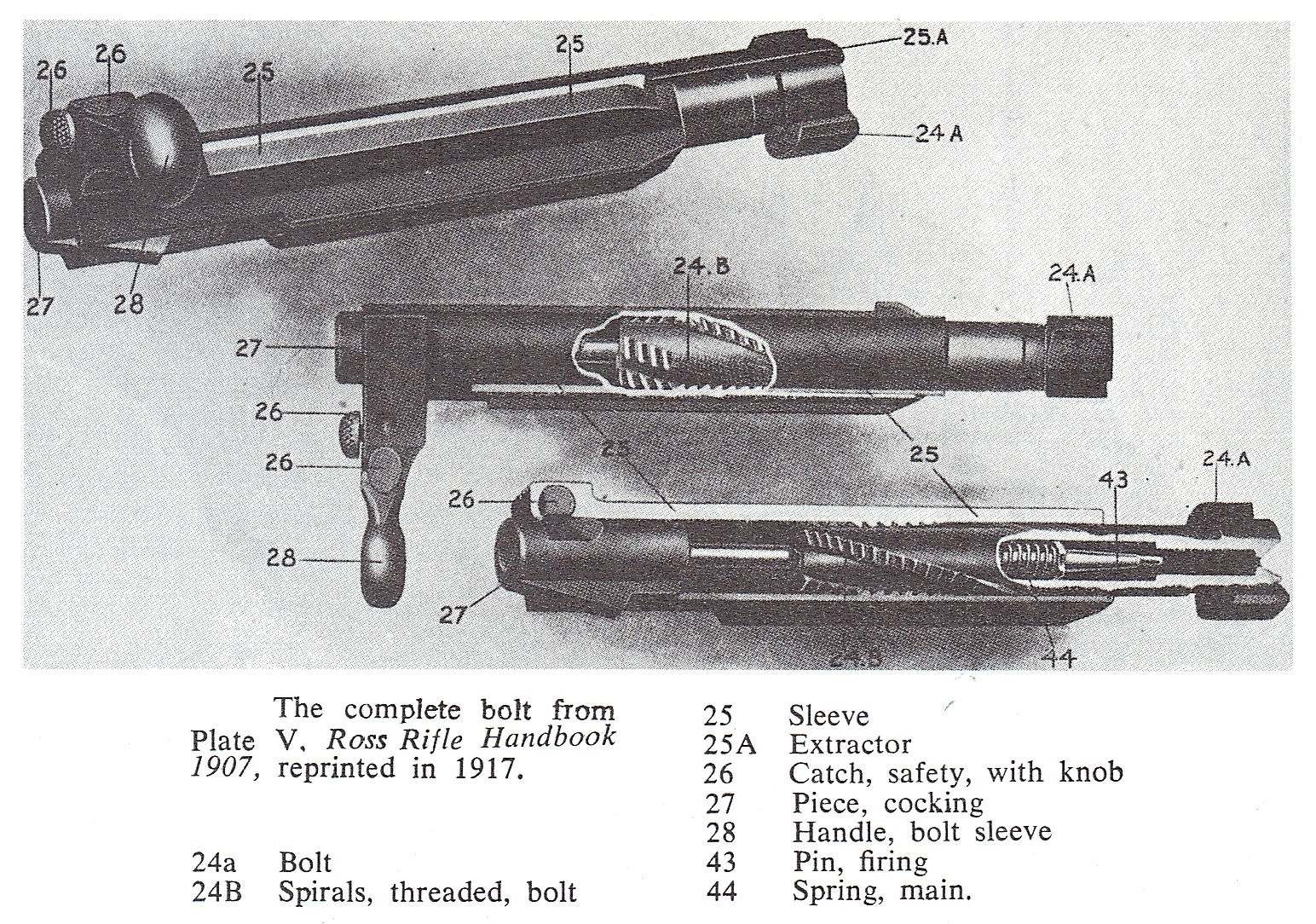

Once the Canadian soldiers arrived at the Western Front it was quickly discovered that the dirt and mud had a marvelous ability to work its way into a Ross Mark III bolt system. The straight pull mechanism worked by having an inner bolt with teeth that engaged in an outer bolt sleeve that was grooved. The teeth in the grooves caused the bolt to rotate for unlocking and locking; however, this mechanism was prone to jamming as dirt found its way in. This led to the next complication; once the rifle was dirty and jamming the soldier would want to do the obvious and clean the dirt out to get it working again, and he would want to do that quickly because he might just have rather a lot of German soldiers bayonet charging his trench whilst he was cleaning his rifle bolt.

There was a second trap for the soldier at the front line with a jammed rifle however. The Mark II Ross Rifle bolt mechanism could not be assembled wrongly, there was only one way it would fit together and that protected the user from the disastrous consequences of getting it wrong. However, the Mark III Ross that Canadian soldiers carried to the Western Front could be re-assembled wrongly in such a way that the rifle could be fired with the bolt unlocked. If the bolt were re-assembled wrongly on a Mark III action the teeth in groove system that rotated the inner bolt would fail to engage causing the bolt to not rotate to lock up in battery, but if the trigger was pulled the firing pin would fall with sufficient force to fire the cartridge. If this happened the bolt would fly back into the shooter’s face. It would most likely be prevented from completely exiting the rifle but it would come back into the shooter’s face causing a horrible injury and there were recorded fatalities.

See the video below from forgottenweapons.com for an excellent demonstration of this.

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EaSui_UqDX8″ /]

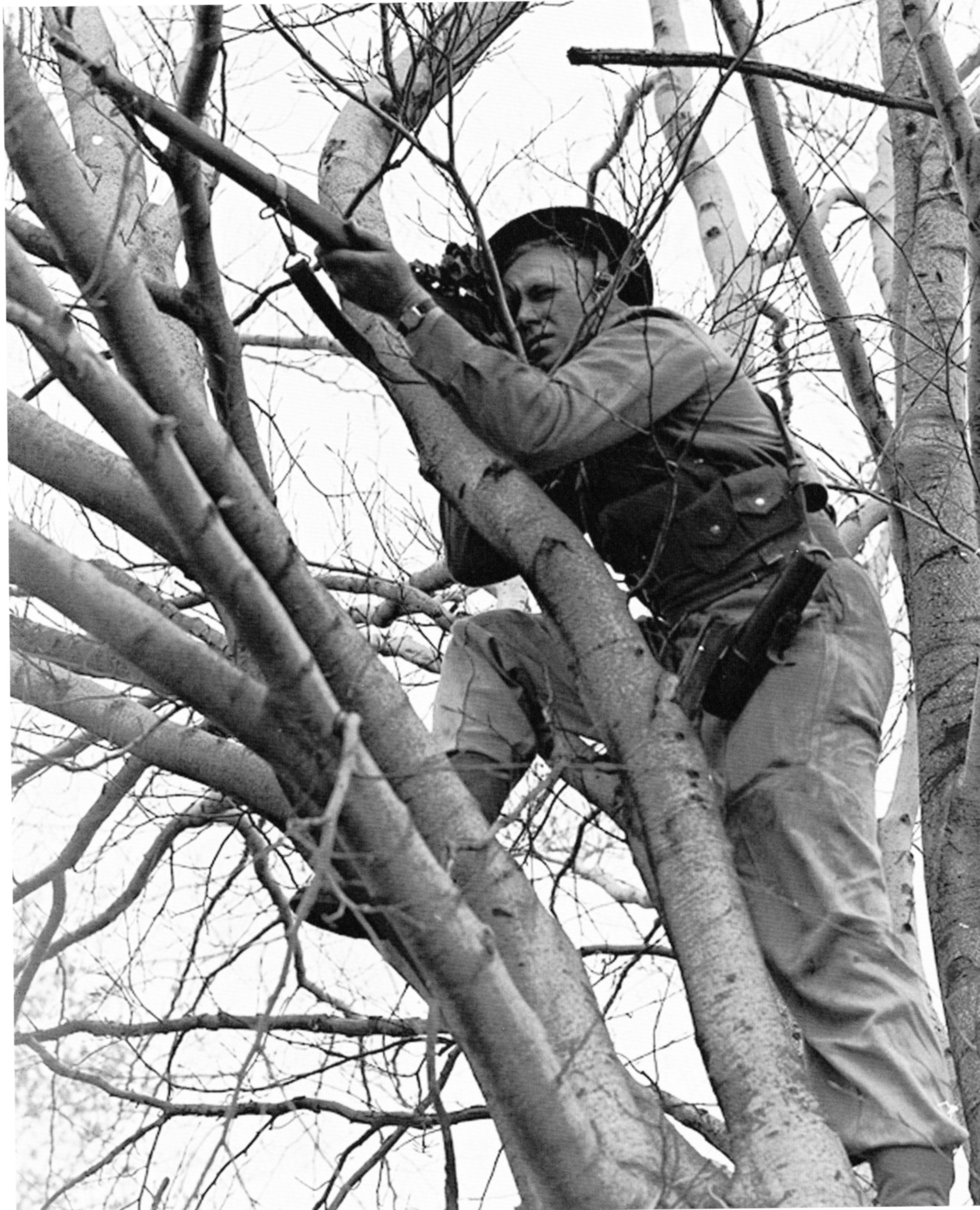

The combined effect of the Ross Mark III jamming and the potential for it to cause injury were more than enough to cause Canadian soldiers to abandon the rifles and salvage Lee-Enfields from casualties. Although the Canadian Government minister responsible for the purchase of the Ross rifles was adamant that the rifles were not a problem the feedback from the front line produced overwhelming evidence that the Ross had to be replaced with Lee-Enfields that were reliable in the front line conditions. There were however one group who wanted to keep their Ross Mark III rifles, the snipers.

If you have the opportunity to shoot a Ross Mark III you will discover why the rifle was preferred by snipers. Not only is the straight pull action a delight to use (if its kept clean) but the trigger is excellent and the aperture sighting system is also excellent. These long rifles with their refined and very well made actions are highly stable and predictable, exactly what a sniper needs. For sniper use some Ross Mark III rifles were fitted with the prismatic telescopic sight by Warner & Swasey which makes them even better.

The Ross Mark III rifles were withdrawn from the 1st Canadian Division at the Western Front in 1915 and from all other Canadian forces shortly after. The Mark III rifles were modified to prevent the bolt from being re-assembled wrongly by the fitting of a rivet in the bolt system. This did not help prevent the rifles from jamming when filled with dirt but it did make the rifles safe.

The Ross Mark III rifles were used in the Second World War as sniper rifles and the remaining ones brought back from the Western Front ultimately found their way into military surplus sales where they were used for hunting, target shooting or as collectibles. If you have a Ross rifle then the Mark II model of 1905 is not able to be re-assembled wrongly and is safe to shoot and enjoy. If you have a Mark III check the video from Forgotten Weapons above to ensure yours is assembled correctly and also to check if it has the rivet fitted that ensures it cannot be assembled wrongly. The Mark III Ross is a very pleasant rifle to shoot and although they were not successful in the mud of the trenches they make a great rifle for hunting or target shooting. As a sporting rifle the Ross Mark III is great and it was made both in .303 British and in .280 Ross. Sadly the .354 Ross did not get into full production but if it had it would have been an excellent African and Asian hunting rifle, also great for trips to Alaska and for big bears in North America.

Sir Charles Ross was educated at Eton and Trinity College Cambridge and was a well known sportsman and big game hunter prior to serving his country in the Second Boer War. He passed away at the age of seventy years at St. Petersburg, Florida having lived a colorful life and having made his mark on world history.

One of the better reference books on the Ross Rifle is “Sir Charles Ross and His Rifle” (published 1969) by Roger Phillips & Jerome J. Knap. This book is out of print to the best of our knowledge but it is listed on Amazon albeit as currently unavailable. You will find that listing if you click here.

Roger Phillips also authored another book in collaboration with F. Dupuis and J. Chadwick “The Ross Rifle Story” published in 1984 which is also listed on Amazon but as unavailable at the present time. You can see that listing if you click here.

(Header image courtesy Othias @ C&Rsenal).

Jon Branch is the founder and senior editor of Revivaler and has written a significant number of articles for various publications including official Buying Guides for eBay, classic car articles for Hagerty, magazine articles for both the Australian Shooters Journal and the Australian Shooter, and he’s a long time contributor to Silodrome.

Jon has done radio, television, magazine and newspaper interviews on various issues, and has traveled extensively, having lived in Britain, Australia, China and Hong Kong. His travels have taken him to Indonesia, Israel, Italy, Japan and a number of other countries. He has studied the Japanese sword arts and has a long history of involvement in the shooting sports, which has included authoring submissions to government on various firearms related issues and assisting in the design and establishment of shooting ranges.