Introduction: The Locomotive That Shouldn’t Have Been Built

The 241P steam locomotive stands out as one of the most beautiful ever created. It might be thought of as being like a classic Bugatti of the rails, and its beauty is arguably the major contributing factor in ensuring no less than four examples of this “flower of French steam locomotives” have survived into the twenty-first century. But the 241P is a locomotive that quite probably should never have been built. In a post-war France devastated by the years of the German invasion and occupation what was needed was a practical and efficient design for heavy passenger trains: a locomotive that could pull an 800 ton train at speeds of 120km/hr (75mph), and that locomotive already existed, it was the André Chapelon designed 240P.

The main impediment to Chapelon’s 240P being adopted as the standard steam passenger locomotive to see France through the years when she would electrify her extensive rail network seems to have been political. People who are mavens of design engineering are often looked upon with envy by other engineers. André Chapelon had, in the pre-war years, been employed as a design engineer on the Paris à Lyon et à la Méditerranée (translated: Paris, Lyon and the Mediterranean, abbreviated as PLM) railway and he had proved his expertise, seemingly to the annoyance of his superiors. This, it seems, had led to his departing the PLM on not so friendly terms and he moved on to work for the Paris Orleans Railway (PO). At the Paris Orleans Railway the young Chapelon was given much more design freedom to put his scientifically tested ideas into practice. He did the math, did the engineering, and produced the results, which were initially disbelieved because the efficiencies he was getting were so good, and achieved using quite moderate modifications to existing locomotives.

In the post-war period the French government decided to nationalize the nation’s rail system and formed the SNCF (Société Nationale des Chemins de fer Français). The design engineering team for the new national rail system featured many engineers from the old PLM railway and so they were inclined to look to pre-war PLM designs to create the new national standard heavy passenger steam locomotive. The old PLM 241C was an imposing looking locomotive that the past PLM engineers themselves had created and had great affection for, and so, despite its shortcomings, it was chosen.

The contract for the construction of these new 241P heavy passenger steam locomotives was awarded to Schneider et Cie., of Le Creusot, who had previously built the old 241C. What is interesting is that Schneider et Cie. quietly consulted with André Chapelon to see what could be done with the design to improve it. Chapelon was thus able to make some improvements to the new 241P design, but it was not possible to fix its most glaring fault, inherited from the 241C, the main frames were under-engineered and prone to flexing. This flexing caused frame cracking in the 241P’s predecessors the 241A and the 241C, and also caused the axle boxes to run hot, thus necessitating more frequent maintenance. The flexing of the frames also caused boiler cracking in the 241P, but instead of completely stripping the locomotives down to reinforce the frames to take the stresses off the boiler mount points, the boilers themselves were reinforced from the inside.

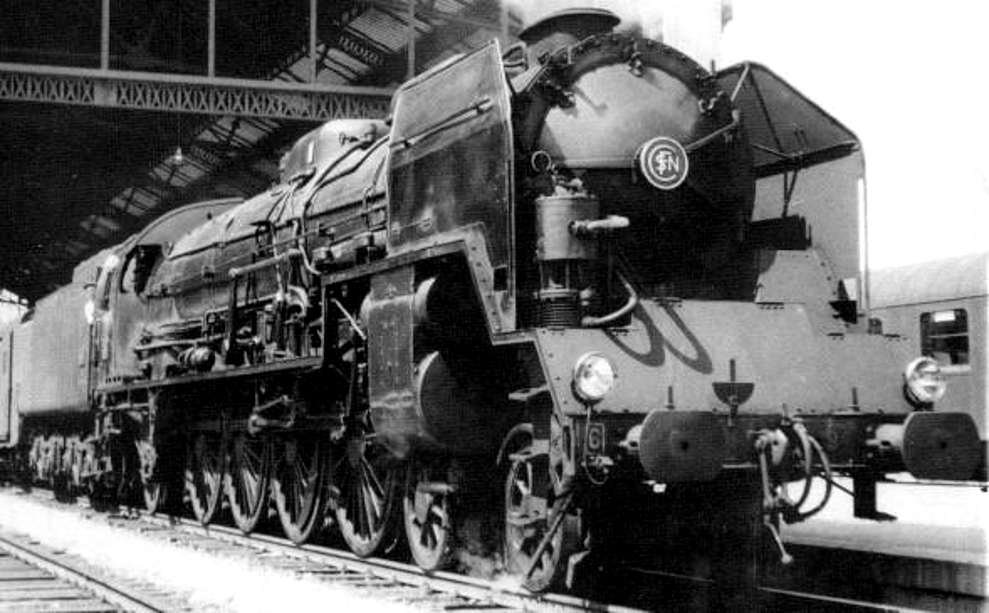

The 241P in Service

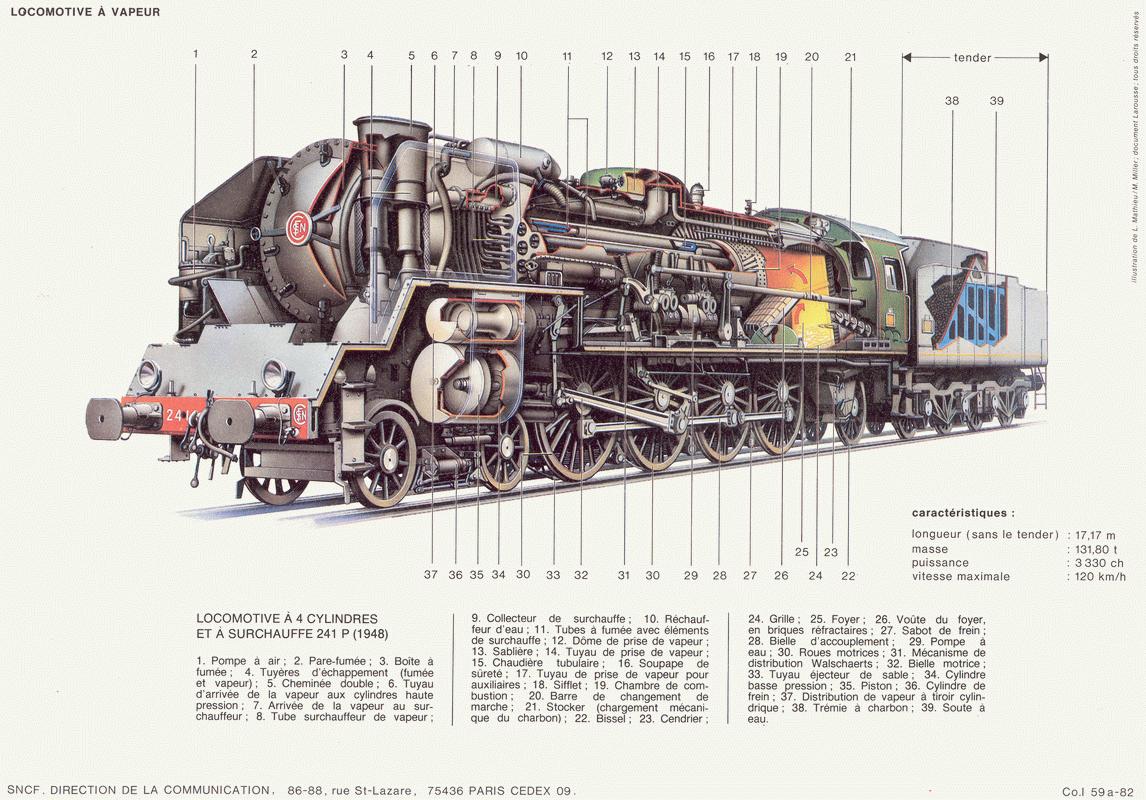

The 241P series of locomotives entered service on the SNCF in 1948 and these magnificent looking machines were first put into service on the Paris to Marseilles route which included hauling France’s premier passenger train, Le Mistral, named after the famous French wind. Painted in SNCF green which included green wheels accentuating the undeniable beauty of this engineering work of art: the 241P was thus able to establish itself in the hearts and minds of French railway enthusiasts and passengers alike as it raced across the countryside hauling the nations most famous train.

The 241P locomotives made a name for themselves not only at the head of Le Mistral, but also with other world famous trains such as the Calais-Mediterranée Express which was re-named Le Train Bleu (i.e. the “Blue Train”) in 1949. The Blue Train transported its pampered passengers in the height of French luxury from Calais to the French Riviera. You could actually catch this train from Victoria Station in London, England and it was a preferred method of travel to the South of France beach resorts for wealthy patrons even in the early years after the Second World War. Sometimes those of us who were not wealthy would venture down to Victoria Station and purchase a platform ticket for the princely sum of one penny, so we could watch the Blue Train depart: and occasionally the crew of the Merchant Navy locomotive that would haul it on the British stage of its journey would allow us to come up into the cab and socialize for a while before they set off into the night.

The Preserved Locomotives

With the electrification of the southerly lines the 35 locomotives of the 241P class were moved to the other regions where they took their turn on other trains, including the exotic Orient Express. They were kept in service up until 1973 when the last of the class was withdrawn. Four 241P locomotives have been preserved, the most famous being 241.P.17 which was the highest mileage member, having completed over a million miles in service. She was subject to a thirteen year restoration at Le Creusot. which was completed in 2006. She is licensed to run on SNCF tracks and is used to haul special trains. The other three examples are static preserved; 241.P.16 is at the National Railway Museum of France at Mulhouse, 241.P.9 is being restored in Toulouse, and 241.P.30 is static preserved in Saint-Sulpice, Neuchâtel, Switzerland.

Technical Information

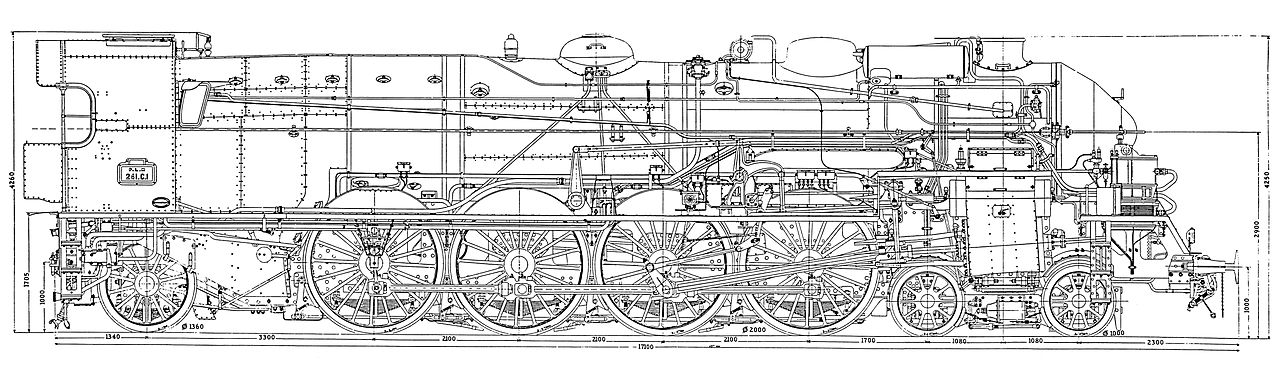

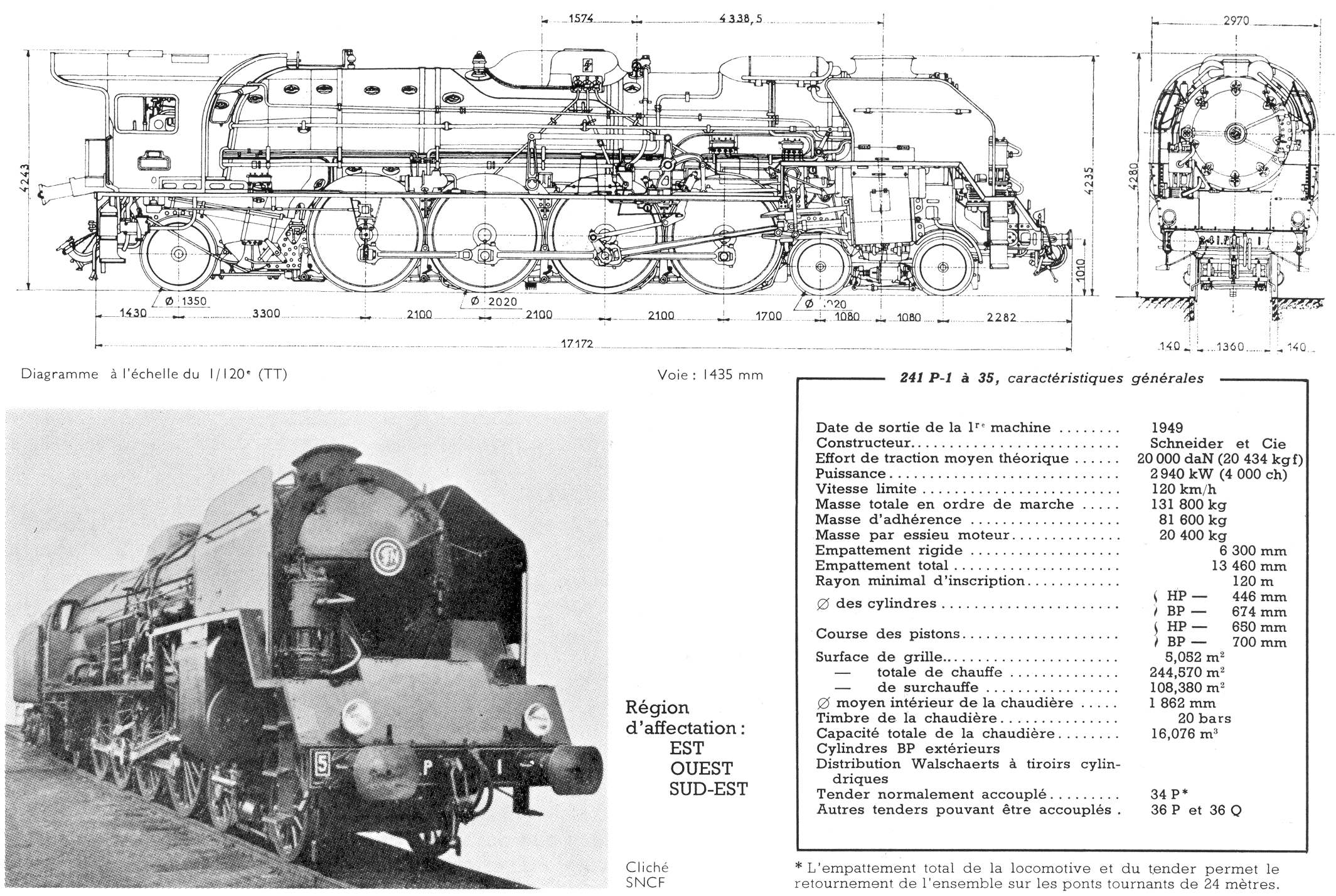

Wheel Configuration: Whyte 4-8-2

Leading diameter: 1,000 mm (39.37 in)

Driver diameter: 2,000 mm (78.74 in)

Trailing diameter: 1,330 mm (52.36 in)

Length: 27.117 m (89 ft 0 in)

Adhesive weight: 81.6 t (80.3 long tons; 89.9 short tons)

Locomotive weight: 131.4 t (129.3 long tons; 144.8 short tons)

Tender weight: 81.6 t (80.3 long tons; 89.9 short tons)

Total weight: 215.4 t (212.0 long tons; 237.4 short tons)

Fuel capacity: 12 t (11.8 long tons; 13.2 short tons) coal

Water cap: 34,050 L (7,490 imp gal; 9,000 US gal)

Firebox:

Firegrate area 5.052 m2 (54.38 sq ft)

Boiler pressure: 20 kg/cm2 (1.96 MPa; 284 psi)

Heating surface: 244.57 m2 (2,632.5 sq ft)

Cylinders: 4 (2 H.P., 2 L.P.)

High-pressure cylinder: 446 mm × 650 mm (17.56 in × 25.59 in)

Low-pressure cylinder: 674 mm × 700 mm (26.54 in × 27.56 in)

Performance figures:

Maximum speed 120 km/h (75 mph) max. service speed

Power output 4,000 hp (3,000 kW)

Tractive effort 202.66 kN (45,560 lbf)

Conclusion

The old saying tells us that “A thing of beauty is a joy forever”. This is probably only true if you are not the one in the workshop keeping the thing of beauty operational. The British Jaguar motor cars made a name for themselves as cars of exceptional beauty, with Enzo Ferrari telling us that the Jaguar E-Type was “the most beautiful car in the world”. Those who owned them tended to discover that they needed to spend a lot of time in the workshop and that they were terribly rust prone. The French 241P is perhaps appropriately regarded as the railway locomotive equivalent of the Jaguar E-Type: fabulous to look at, but the cause of much wailing and gnashing of the teeth in the workshop. As with so many choices people make in life, logic doesn’t always enter into it. But then again, do we really want our lives to be ruled by cold hard logic like Star Trek’s Mr. Spock when beauty and romance are so much more attractive?

(Feature image at the head of this post courtesy thierry.stora.free.fr).

Jon Branch is the founder and senior editor of Revivaler and has written a significant number of articles for various publications including official Buying Guides for eBay, classic car articles for Hagerty, magazine articles for both the Australian Shooters Journal and the Australian Shooter, and he’s a long time contributor to Silodrome.

Jon has done radio, television, magazine and newspaper interviews on various issues, and has traveled extensively, having lived in Britain, Australia, China and Hong Kong. His travels have taken him to Indonesia, Israel, Italy, Japan and a number of other countries. He has studied the Japanese sword arts and has a long history of involvement in the shooting sports, which has included authoring submissions to government on various firearms related issues and assisting in the design and establishment of shooting ranges.