Introduction: One Pistol to Rule Them All

You don’t have to be involved in the shooting sports for long before you will hear the name “Mauser”, often in conjunction with discovering Paul Mauser’s definitive bolt action rifle design, the Mauser ’98. German firearms designer Paul Mauser’s M98 was by no means his only design however, it just happens to have been his most successful.

Almost as well known as the M98, which formed the basis for the German Military Gewehr 98 of World War I fame and Karabiner 98k of World War II, was Mauser’s C96 semi-automatic pistol which is most often referred to as the “Broomhandle” Mauser because of the shape of its grip. This pistol’s fame came to it in part because it was Winston Churchill’s favorite (although legend has it that he changed his mind when he discovered the Colt M1911). The “Broomhandle” was also used in China, where lots of Chinese copies were made, and during the Russian Revolution where it became known as the “Bolo” Mauser: the “Bolo” being short for Bolshevik.

But there was another Mauser pistol, one that was not Winston Churchill’s favorite, one that was not associated with great political upheavals, but one that was a quiet achiever that sold around half a million copies across its model variants, and that pistol was a design that was originally conceived around 1908-1909 and which became best known as the production models of 1910 and 1914.

Paul Mauser’s vision for his new semi-automatic pistol was to create a design that could be essentially scaled up or down to suit the cartridge it was to be used for. These designs were most probably created by an engineer named Josef Nickl whom Mauser had employed in 1904. Nickl produced designs for pistols in 9mm Parabellum, .45 ACP, 7.65 Automatic (.32ACP) and 6.35mm (.25ACP). His designs for the .45ACP and 9mm Parabellum used a delayed blowback system and his designs for the smaller cartridges were of a straight blowback design.

The 45 ACP and 9mm Parabellum Mauser Pistols

Mauser’s design for a full size military pistol used a quite unusual delayed blowback system that featured a pair of arms in the frame ahead of the trigger guard that engaged into machined angled surfaces in the slide. When the pistol was fired the slide and barrel recoiled together with the friction between the angled surfaces on the arms and slide delaying the unlocking of the action until the breech pressure had dropped to a safe level. When the arms were forced down the slide and barrel unlocked allowing the slide to recoil to battery. In Mauser’s early design there was an unusual recoil buffer spring (Rückstoßpufferfeder) at the rear of the frame to absorb the impact of the slide hitting the frame at battery.

The .45ACP prototype was the subject of a Forgotten Weapons video a few years ago and Ian of Forgotten Weapons provides a clear demonstration of this pistol and is mechanism.

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5lPRZzTC084″ /]

The delayed blowback Mauser pistols in 9mm and .45ACP did not prove to be successful as military designs: the German Military adopted the P08 Luger while the US Military adopted John M. Browning’s Colt M1911. Even the stodgy British, who tended to regard an automatic pistol as “dashed unsporting”, created their own in the form of the William Whiting designed Webley Mk I pistols adopted by the Royal Horse Artillery in 1913 and Royal Navy in 1914. So Paul Mauser’s original idea of creating one basic pistol design to suit all customers did not eventuate. Not to be defeated however Mauser had from the outset also been working on smaller caliber pocket pistols for civilian and police customers.

The Mauser “Model 1910”

Despite the fact that Mauser’s company did not actually refer to their designs by model, but rather by caliber, so the two smaller Mauser pistols that were produced in large quantities have tended to be referred to by collectors by model year. The M1910 is the nomenclature applied to the smallest of these handguns that was chambered for the 6.35mm cartridge (.25ACP) and the M1914 model name for the 7.65mm (.32ACP) pistol.

The 6.35mm Browning (.25ACP) chambered Mauser Model 1910 was actually introduced in Europe in 1906 and into the USA two years later. This pistol was a straight blowback design, not having the complexity of the delayed recoil locking system used for the 9mm Parabellum and .45ACP versions. The pistol was made to be simple, reliable, and easy to maintain.

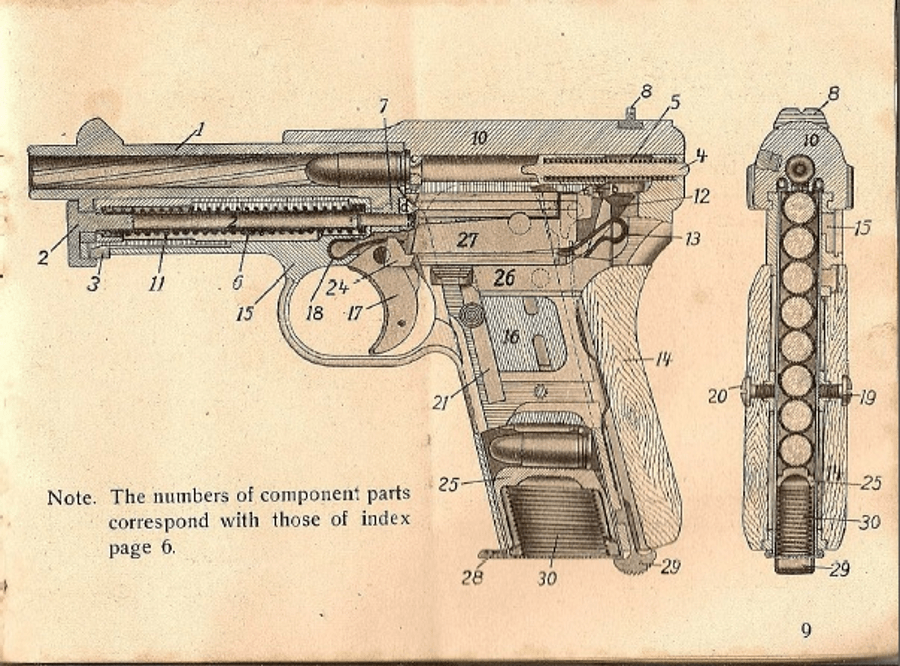

As can be seen from the picture above the fixed barrel was made to be easily removable: it was held in place by the long pin at the bottom of the picture which was also the recoil spring guide rod.

The first variant of the Model 1910 was the “Side Latch”, which featured a rotating side-latch just above the trigger which enabled the cover over the side of the lockwork to be removed for cleaning. The second variant was the “New Model” typically referred to as the “Model 1910/14” because it first appeared in 1914. The original side-latch model created some potential problems when field stripped as the trigger could be removed, but would be difficult to replace because of the spring pressure on it. The New Model eliminated this issue and provided some other changes to the lockwork including improvements to the interrupter mechanism, and the magazine and slide stop mechanisms. The New Model’s change to the striker mechanism also made it easier to determine if the pistol was cocked.

The pistol was single action, and striker fired, with the trigger connected to a bell crank lever which rotated around its center to disengage from the striker sear, allowing it to fly forward under spring pressure and discharge the cartridge.

The mechanism for the Model 1910 6.35mm and Model 1914 7.65mm pistols is the same and can be visually appreciated in the video below from C&Rsenal

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rqkjk9WlC34″ /]

To operate the pistol it must first be opened, but the slide cannot be opened unless a magazine is inserted. If an empty magazine is inserted then the slide can be pulled back and will lock in place. If the empty magazine is removed the slide will remain locked open: however, if an empty magazine is inserted and pushed home the slide will close.

If the magazine is loaded with cartridges then when it is inserted into the pistol and pushed all the way home the slide will fly forward chambering a cartridge. This was a very convenient feature ensuring the speediest reload as there was no need to operate the slide to get the pistol into action, as soon as the loaded magazine was inserted the slide would automatically close and the pistol was good to go. So the design was very well thought out.

The safety catch of the 6.35mm Model 1910 is a lever to the rear of the trigger which is pressed down to engage. Once the safety lever is pressed down it locks in place and cannot just be pushed back up: instead the locking button located just below it is pressed, this causes the safety to fly up under spring pressure and disengage so the pistol can then be fired.

There were a number of variants of the 6.35mm “New Model” pistols including the post World War I commercial models, 1934 Transitional Model, and the “Model 1934” which is distinguished by its more rounded ergonomic grip.

For a full and detailed description of the history and model variants of the Mauser 6.35mm “Model 1910” see Ed Buffaloe and Burgess Mason III’s article on unblinkingeye.com

The Mauser “Model 1914”

The development of Paul Mauser’s small pistols was well underway by around 1908: around this time he told the Deutsche Versuchs-Anstalt für Handfeuerwaffen (the German Experimental Laboratory for Handguns) that his company would be producing a small 7.65mm pistol “…not larger in weight and size than the well-known Browning 7,65 pistol…,” (Note: See “Paul Mauser: His Life, Company, and Handgun Development 1838-1914” by Mauro Baudino & Gerben van Vlimmeren).

The pistol we nowadays refer to as the Mauser “Model 1914” was the 7.65mm (.32ACP) version and development work on it began after the “Model 1910” was in production. The design of the pistol was almost identical to that of the 6.35mm “Model 1910” but scaled for the larger and more powerful .32ACP cartridge.

The 7.65mm Mauser pistol was aimed at the police market, and the 7.65mm cartridge had already become the caliber of choice for many police departments in Europe. The first version of the 7.65mm Mauser pistol featured a “humpback” shape of the slide in which the thickness of the metal around the ejection port and forward from there was of smaller dimensions than the rear. The logic behind making the ejection port area less thick makes sense in terms of ensuring easier ejection of fired cases, while the thicker metal at the rear of the slide provides additional mass to absorb the recoil power of the 7.65mm cartridge.

The action of the “Model 1914” was largely the same as that of the “New Model” 6.35mm pistols and featured the same improvements to the trigger and interrupter mechanisms, and the magazine mechanisms that blocked the slide open when the magazine was empty, and prevented the pistol from being fired if the magazine was removed.

Operation of the Mauser automatic pistol explained with field stripping by Larry Potterfield of Midway USA

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HWx70YkrfHQ” /]

With the Model 1914 “humpback” pistol in production Mauser decided that the additional machining to produce the humpback shape was not actually necessary and so a new design was introduced which eliminated it.

There were many variations of the 7.65mm Mauser pistols including those purchased by the German Reichsmarine, Kriegsmarine, Weimer Navy, Weimer Police, and the Norwegian Police are examples.

The last major revision to the design of the Model 1914 came with the Model 1934, which, like the 6.35mm version, was given a more rounded pistol grip.

You can find a full and detailed description of the many model variants of the Model 1914 7.65mm (.32ACP) pistols by Ed Buffaloe and Burgess Mason III’s on unblinkingeye.com in the second part of their article.

Conclusion

The Mauser automatic pistols were intelligently designed and proved popular with a great many having been produced, and many exported to the United States. They were made to Mauser’s very high quality standards, are known to be a reliable pistol, capable of decent accuracy, and providing a good level of safety for examples that are in good condition. There are many variants of these pistols and some are worth more money on the collector market than others. But if you have one of these in your “I’ve got this old gun” drawer somewhere it might be worth dusting it off and taking it to the range for some shooting fun. Just make sure you give it a good clean up before you do that, and preferably check its function with some snap caps to make sure its working OK. Better still have a gunsmith give it the once over before you put live ammo in it, bearing in mind that it will be an old gun and we need to be cautious when shooting old guns in case something is worn out: just as we normally do some maintenance on an old car before we try to start the engine or drive it.

Ammo for these pistols is common, which makes them a great shootable collectible.

Jon Branch is the founder and senior editor of Revivaler and has written a significant number of articles for various publications including official Buying Guides for eBay, classic car articles for Hagerty, magazine articles for both the Australian Shooters Journal and the Australian Shooter, and he’s a long time contributor to Silodrome.

Jon has done radio, television, magazine and newspaper interviews on various issues, and has traveled extensively, having lived in Britain, Australia, China and Hong Kong. His travels have taken him to Indonesia, Israel, Italy, Japan and a number of other countries. He has studied the Japanese sword arts and has a long history of involvement in the shooting sports, which has included authoring submissions to government on various firearms related issues and assisting in the design and establishment of shooting ranges.