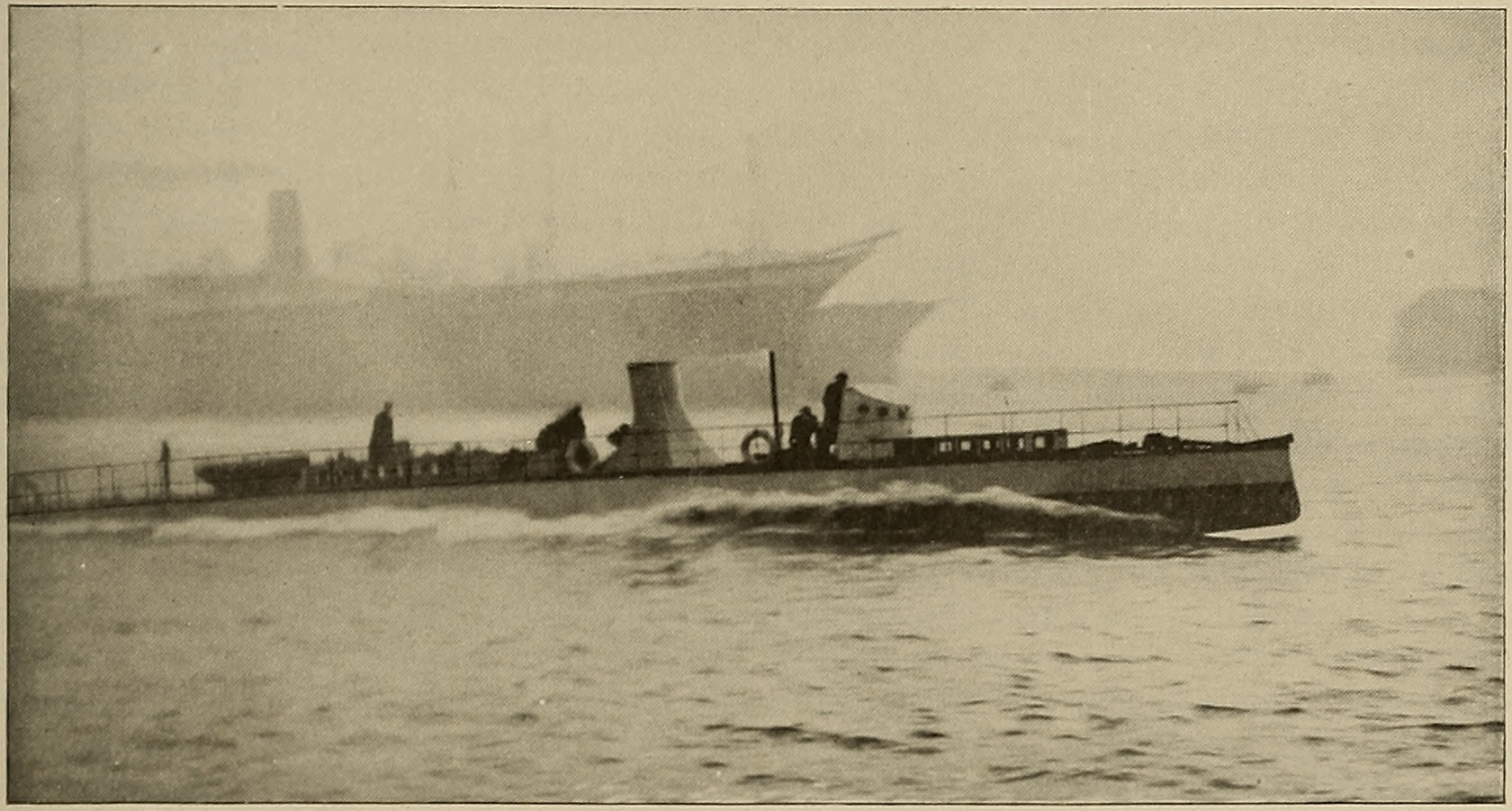

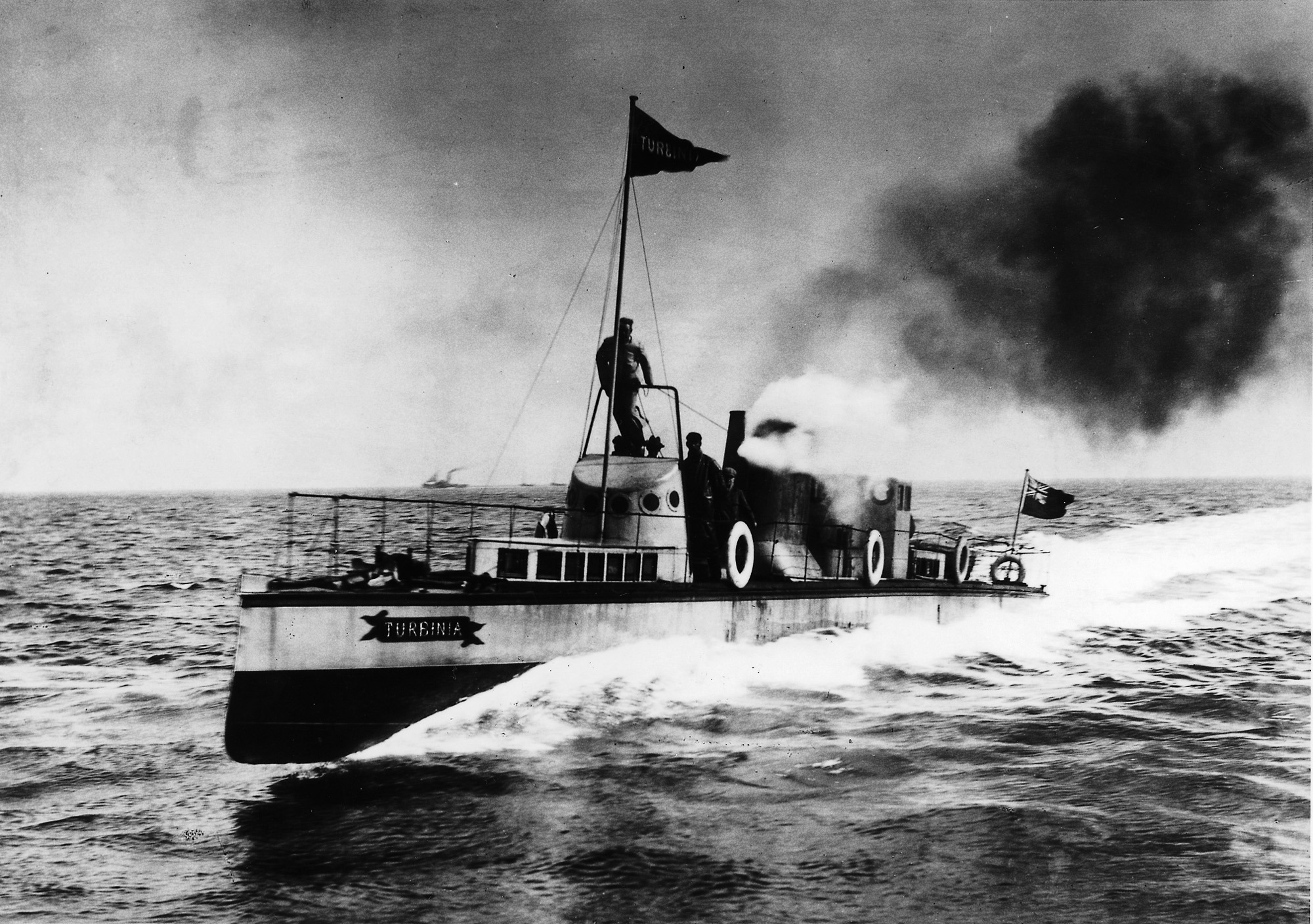

The Turbinia was a small vessel made to demonstrate a new marine propulsion technology that its creator, Charles Parsons, hoped would result in contracts with Britain’s navy and her merchant navy.

She was used to stage an outlandish publicity stunt at the naval parade staged for Queen Victoria’s Silver Jubilee in June of 1897, where she was able to speed between the ponderous warships on parade and easily outpace the pursuit boat sent out to capture her.

No doubt this caused sputtering red-faced rage for some and great mirth for others as their tears of laughter dripped into their tea cups.

Fast Facts

- Turbinia was a demonstration small ship made to research and develop marine steam turbine propulsion technology.

- Turbinia and her multi-stage steam turbine was the brainchild of Charles Algernon Parsons, a gifted and visionary engineer.

- Parsons first demonstrated Turbinia with an impromptu show at the Naval parade held in honour of Queen Victoria’s Silver Jubilee in 1897. It was a show of speed that rendered the existing ships of the Royal Navy obsolete.

- The Royal Navy’s adoption of steam turbine powered ships began the year after the Turbinia’s demonstration and has continued through to the present day.

- Parsons’ steam turbine technology not only became a mainstay for ship propulsion but also for electrical power generation and even nuclear power plants use multi-stage steam turbines to drive their generators.

Some people have a natural penchant for mathematics – which is a puzzle for me because I’m not the slightest bit math inclined. I remember coming into a room years ago and seeing a friend avidly reading a book on calculus. I said to him, with some incredulity, “You’re reading a book on calculus” to which he replied with great enthusiasm “Yes, its so interesting”.

So “horses for courses”, some have a love for mathematics, and some do not, but Charles Algernon Parsons was one who loved mathematics from an early age and that love shaped his life, and also shaped the technology behind electrical power generation, and ship propulsion, including the propulsion systems used on modern nuclear powered submarines.

Charles Parsons was born in 1854 and graduated from Cambridge University in 1877 with a First Class Honours Degree in engineering.

Parsons obtained a position at the W.G. Armstrong engineering and shipbuilding company located on the River Tyne in the north east of England: and it was in this job that he first explored the idea of using a steam turbine for electrical power generation.

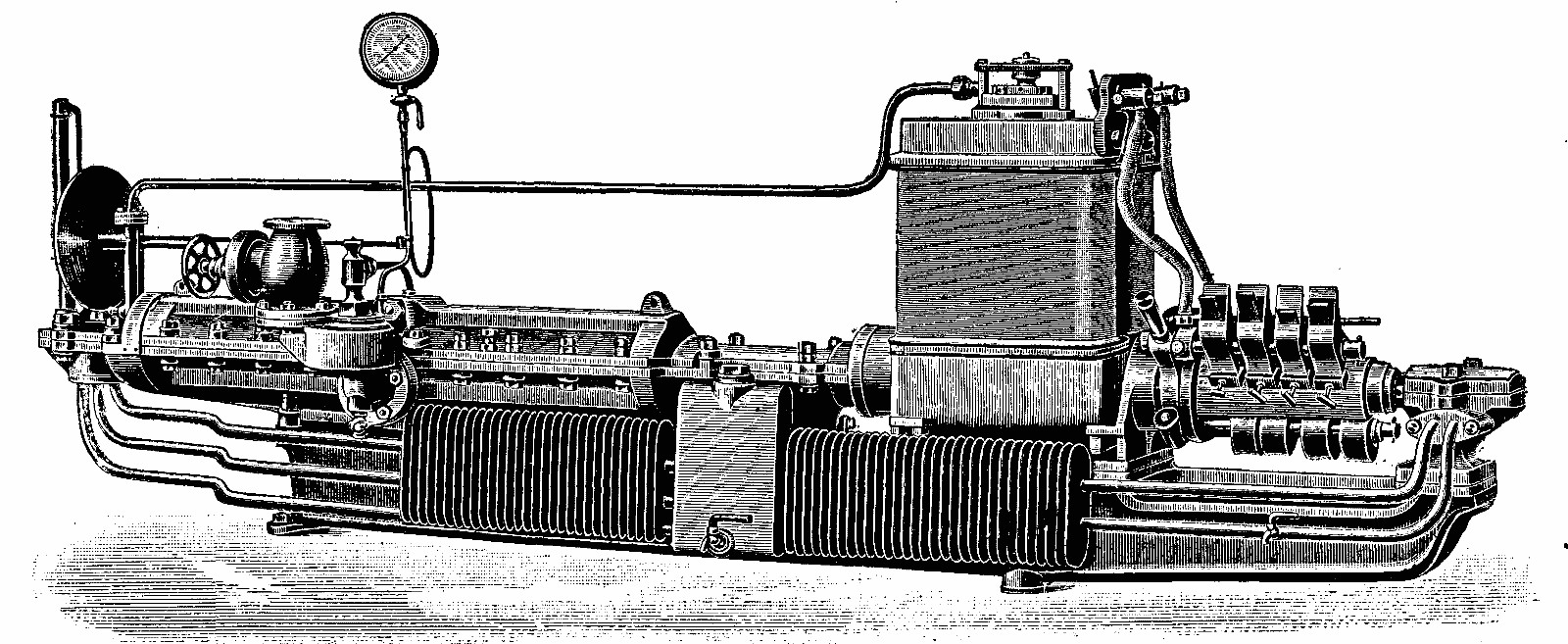

To achieve the sort of efficiency he was seeking Charles Parsons borrowed the idea of staged expansion of the steam. It was common practice in reciprocating steam engines of the time to use double, triple or quadruple expansion, which involved sending the high pressure steam to small high pressure cylinders first, then to medium sized medium pressure cylinders, and then to large lower pressure cylinders: this whole process intended to maximize the energy of the steam expansion by staging it multiple times instead of just harvesting the energy once.

One of the greatest designers of railway steam locomotives who used this kind of staged expansion compound engines was Frenchman Andre Chapelon.

Charles Parsons created the first modern steam turbine using the staged expansion principle in 1884 and applied it to power generation. His first compound steam turbine was made in 1887.

Parsons had begun his engineering career in an engineering and shipbuilding company and his forward thinking led him to establish a company of his own with which to develop his ideas both into the realms of electrical power generation and ship propulsion. So it was that he established the C.A. Parsons & Co. in 1889 and having done so wasted no time in designing a steam turbine powered small ship with which to test and develop his ideas.

Although Parsons was not a trained naval architect he was interested in boats and ships and had spent his fledgling engineering years working for a company that built ships – so he had made a point of educating himself in ship design. Armed with that knowledge he set about creating a small ship that would demonstrate the potential of steam turbine propulsion.

To achieve this end the ship needed a racing boat style of hull with a narrow beam and hydrodynamics that would enable it to exceed 30 knots. However the vessel would need to be stable for maneuvering at speed. The hull would also need to accommodate the steam boiler and triple expansion turbine machinery.

Parsons accomplished this, and decided to keep things as simple as possible by using a single suitably large propeller to deliver the power from the turbine to the water. This is where things initially fell apart. Thus equipped the vessel, which Parsons named the Turbinia, could not get above 20 knots.

Parsons suspected he knew what the problem was, the propeller was spinning too fast for the water to accept the movement of the propeller and transmit that power – the propeller was rotating so fast it was creating air space around itself – a phenomenon known as “cavitation”.

In Parsons’ mind the way to solve this problem was to spread the load across multiple smaller propellers and to test this theory he constructed a cavitation chamber.

With the results of his experiments Parsons fitted the Turbinia with three propeller shafts each fitted with three propellers – making nine in total. This indeed solved the cavitation problem and allowed the Turbinia to reach a speed of 34.5 knots (i.e. 39.7 mph or 64 km/hr).

What was needed next was a suitable publicity stunt to get the undivided attention of Britain’s navy and the upcoming naval parade to be held to celebrate Queen Victoria’s Silver Jubilee in June 1897 presented the ideal opportunity.

It is likely that informal permission to stage his demonstration of the capabilities of Turbinia had been given to Parsons via senior contacts in the navy – who had been following his progress with great interest.

So it was that on the day of the great parade of Queen Victoria’s navy the diminutive Turbinia zoomed in and out around the ponderous battleships and even the pursuit boat sent out to intercept her didn’t have a hope of doing so – the pursuit boat almost got herself swamped in Turbinia’s quite impressive wake created by those nine fast rotating screws.

Turbinia’s display so impressed the Lords of the Admiralty that immediate plans were put in place to use this new technology in a new generation of British warships.

The navy commissioned the building of two new warships to be fitted with Parsons’ turbine machinery, the first was HMS Viper which was ordered less than a year after the Turbinia demonstration, Viper being ordered on 4th March 1898 and launched on 6th September 1899.

The second ship was the HMS Cobra which was launched on 28th June 1899 and entered service on 8th May 1900.

Both these ships were built by Armstrong Whitworth and to construct the turbine machinery Charles Parsons established the Parsons Marine Steam Turbine Company in 1897 – the year of his demonstration of Turbinia’s capabilities.

Although both HMS Viper and HMS Cobra were lost to accidents, both in 1901, this was no fault of their machinery and the British Navy set about the complete modernization of their fleet with turbine equipped warships.

The most notable new ship design that materialized powered by steam turbine machinery was HMS Dreadnought, a new heavily armoured battleship equipped with 12 inch (305 mm) main guns mounted in armoured turrets.

Her turbine machinery enabled her to have a top speed of 21 knots (24 mph or 39 km/hr).

Steam turbine machinery found its way into passenger ship service also with the 31,938 Gross Registered Tonnage Cunard passenger liner Mauretania which, like the Dreadnought could make 22 knots.

The steam turbine pioneered by Charles Parsons went on to become a mainstay power source for ships, both naval and commercial. Some passenger ships such as the SS Canberra of Pacific & Orient Lines used a steam turbine/electric drive which proved to be an excellent combination. The SS Canberra is famous for its use as a troop ship for the 1982 Falklands war – she was one of very few passenger ships fast enough to keep up with the warships of the British naval task force sent to counter the Argentinian invasion. She was a ship I had the privilege of traveling on in the early 1960’s on a voyage from Britain to Australia.

Parsons’ steam turbine machinery paved the way for ship propulsion and efficient electricity generation. Whether power stations use coal or nuclear power to heat the water and create steam that steam is then channeled through a steam turbine that owes its creation to Charles Algernon Parsons.

In the same way modern nuclear powered submarines use a nuclear reactor to heat water into steam and that is fed into a multi-stage steam turbine to give these ships underwater speeds in excess of thirty knots.

Small though she was, the Turbinia pioneered both modern power generation and ship propulsion, especially warship propulsion.

Jon Branch is the founder and senior editor of Revivaler and has written a significant number of articles for various publications including official Buying Guides for eBay, classic car articles for Hagerty, magazine articles for both the Australian Shooters Journal and the Australian Shooter, and he’s a long time contributor to Silodrome.

Jon has done radio, television, magazine and newspaper interviews on various issues, and has traveled extensively, having lived in Britain, Australia, China and Hong Kong. His travels have taken him to Indonesia, Israel, Italy, Japan and a number of other countries. He has studied the Japanese sword arts and has a long history of involvement in the shooting sports, which has included authoring submissions to government on various firearms related issues and assisting in the design and establishment of shooting ranges.