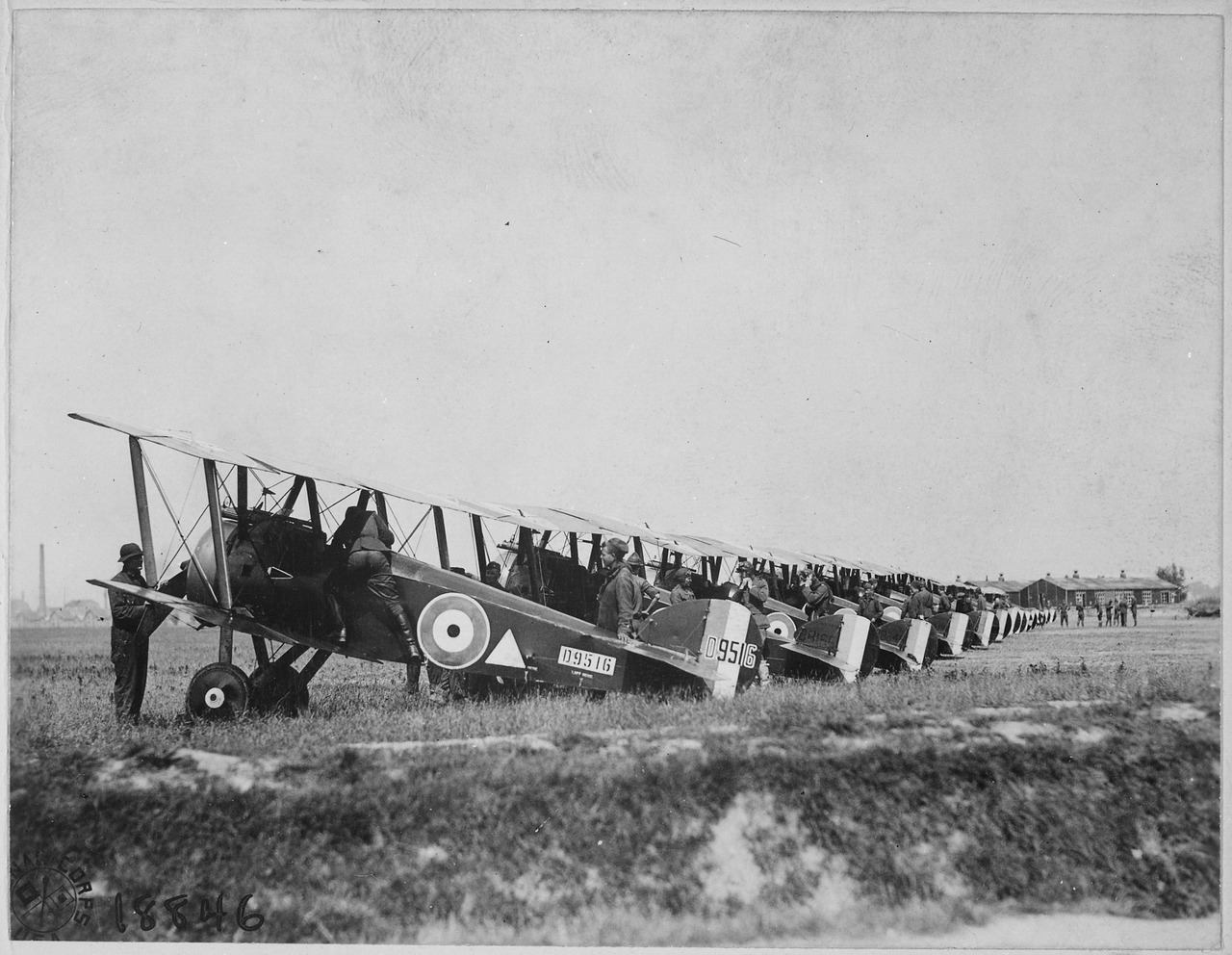

The Sopwith Camel has been immortalized in popular culture as Snoopy’s imaginary World War I fighter as he engages with “The Red Baron” over the trenches of the Great War. But there’s a lot more to the Sopwith Camel than just being Snoopy’s dog-fight plane. It was the single most successful fighter aircraft of the First World War, flown by pilots from Britain, the United States, Australia, New Zealand, and various other countries. Curiously it was a great success as a combat aircraft in part because it was dangerous to fly, just as a highly strung racehorse can be dangerous to ride.

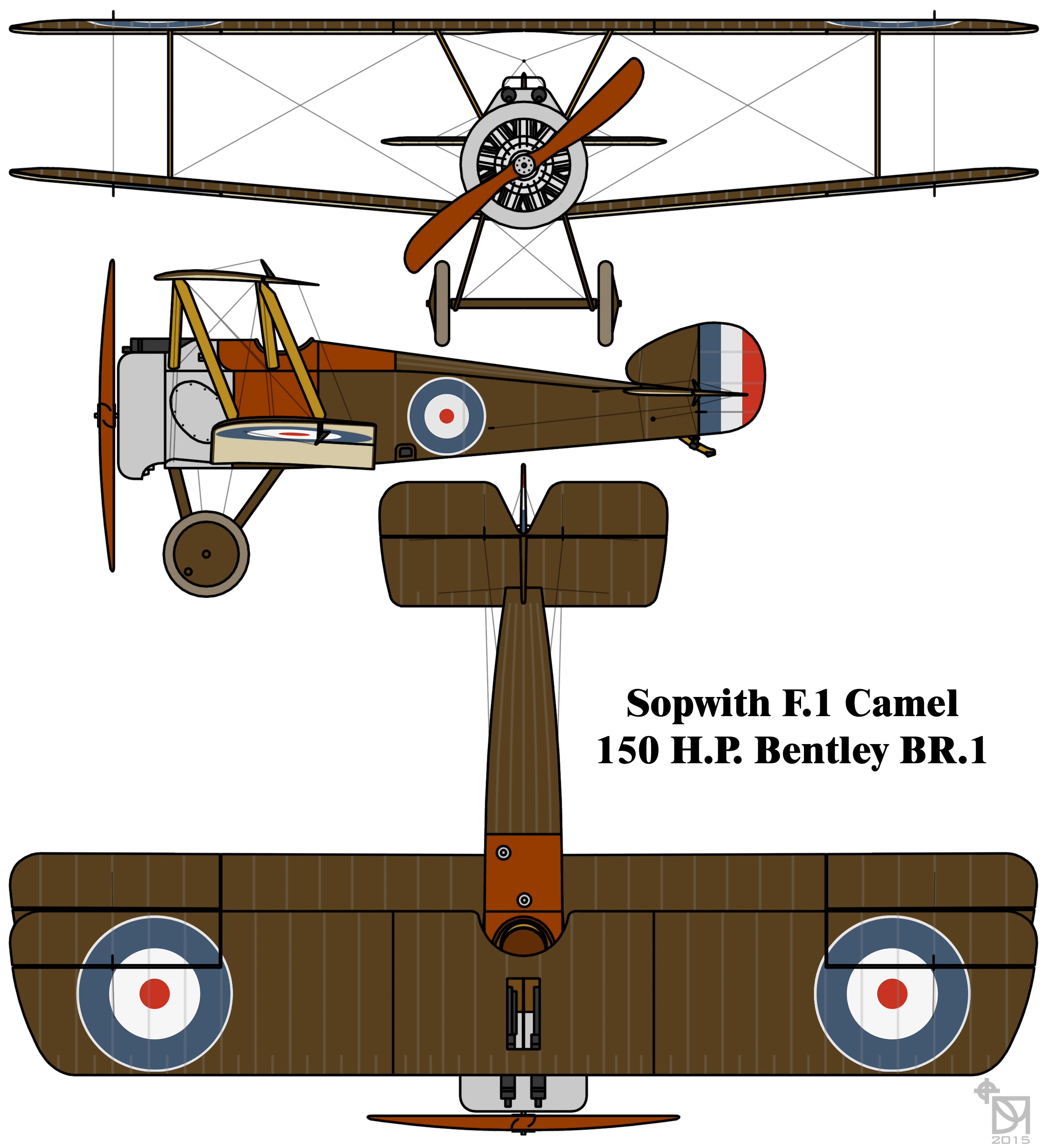

The Sopwith Camel was the most famous model of the First World War Sopwith fighters, the first being the Sopwith Pup, the second being the Sopwith Triplane, followed by the Sopwith Camel. The Sopwith Camel’s correct name was the Sopwith F.1. and it acquired its nickname “camel” from the metal hump over the twin Vickers belt-fed .303 British machine guns fitted to many versions of the aircraft. The hump shaped cover over the Vickers machine guns was put there to prevent them freezing, particularly at higher altitudes. Meeting the “Red Baron” and his “Flying Circus” with a pair of frozen machine-guns would be an inconvenience to be avoided.

The Sopwith Camel’s predecessor, the Sopwith Pup, had a reputation for being quite predictable and docile to fly. This was probably just as well as flying machines were a new thing and not many recruits could be expected to have any flying experience. However, the Pup had to face off against German aircraft that were becoming increasingly maneuverable to the point where it was realized that the Pup needed to be replaced with an aircraft that could out maneuver the enemy aircraft, and out-gun them. It was for this that the Sopwith Camel was created.

The Sopwith Camel was made with the main weight of the aircraft compressed into the front seven feet of the aircraft. The logic behind this was the same logic that is applied to a fine English gun. In order for a gun to handle quickly the weight must be concentrated “between the hands”, i.e. in the central portion around the action: the barrels and butt-stock being kept light. Applying this same principle the design consultant for the Sopwith Camel, Australian Harry Hawker, kept the heavy components concentrated in a short area at the front of the aircraft to make it quickly maneuverable. This worked perfectly but at the same time created an aircraft that was so sensitive to pilot input that it became easy for a pilot to get things a bit wrong, potentially with fatal results.

The main contributing factor in making the Sopwith Camel such an unforgiving aircraft to fly was the torque effect of the radial engine. The radial engines used in these early First World War aircraft were different to radial engines that came later. In these early engines, such as the 130hp Clerget 9B with which many Sopwith Camels were fitted, was that the crankshaft remained stationary whilst the cylinders and crankcase rotated. This meant that the main mass of the engine was rotating causing a massive torque effect. The upside was that this torque effect could be used to turn the aircraft sharply, something that was very useful in a dog-fight.

When the “Red Baron” and his “Flying Circus” first encountered the Sopwith Camels they realized they were superior to the German aircraft and that the Germans in turn would need a new aircraft to compete with them. As it was the Sopwith Camel was a huge success as evidenced by its achieving 1,294 kills, more than any other aircraft during the First Wold War.

The Sopwith Camel was first cleared for flight at Brooklands in late December of 1916 and made its first flight soon after that. It entered service in mid-1917 and began earning a name for itself soon after that. The Sopwith Camel 2F.1 was primarily made for the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) and was slightly different being fitted with a more powerful 150hp Bentley BR.1 radial engine which proved to be more reliable than the other engines used in the Camel.

The Sopwith Camel versions were fitted with a range of engines including the 130hp Clerget 9B and 140hp 9Bf, 150hp Bentley BR.1, and Gnome Monosoupape 100hp 9B-2 and 160hp 9N. The most common machine gun synchronization system (the system that ensures the machine guns do not fire into the propeller but only whilst the blades are not in front of the muzzle) was the Sopwith-Kauper gear system, whilst Camels fitted with the Le Rhone engine were fitted with the more reliable hydraulic Constantinesco system.

The Sopwith Camel F.1 model with the 130hp Clerget engine was capable of 117mph whilst the 2F.1 with the 150hp BR.1 could manage 125mph. Operational ceiling was 20,000 feet.

There were a number of variants made for specific roles including a night fighter version nicknamed the “Comic” which was fitted with twin Lewis machine guns mounted above the upper wing in Foster mounts: this being done to avoid having the gun’s muzzle flash in front of the pilot’s eyes which would destroy his night vision. Another version, the T.F.1, was made for a ground attack role and had downward facing machine guns and some armor in the floor to protect the pilot.

If you are interested in owning a Sopwith Camel, and preferably one that does not have the difficult flying characteristics of the original, but which does have the maneuverability and sheer enjoyment factor, then you might want to visit the Airdrome Aeroplanes website as they make replica’s of many First World War aircraft including a brilliant Sopwith Camel (Pictured above), complete with a modern radial engine.

You will find their website if you click here.

A Sopwith Camel from Airdrome Aeroplanes would turn a Snoopy style fantasy into an amazingly fun reality.

These replicas are powered by a Rotec radial engine. The video below from Light Sport and Ultralight Flyer should whet your appetite.

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FG6fbI6bWoY” /]

If you would like a Sopwith Camel workshop manual then such a thing is published by Haynes and you can find it on Amazon if you click here.

Jon Branch is the founder and senior editor of Revivaler and has written a significant number of articles for various publications including official Buying Guides for eBay, classic car articles for Hagerty, magazine articles for both the Australian Shooters Journal and the Australian Shooter, and he’s a long time contributor to Silodrome.

Jon has done radio, television, magazine and newspaper interviews on various issues, and has traveled extensively, having lived in Britain, Australia, China and Hong Kong. His travels have taken him to Indonesia, Israel, Italy, Japan and a number of other countries. He has studied the Japanese sword arts and has a long history of involvement in the shooting sports, which has included authoring submissions to government on various firearms related issues and assisting in the design and establishment of shooting ranges.