Have you ever wondered why, in his James Bond novel “Live and Let Die“, Ian Fleming decides to have Bond driving a Studebaker? Perhaps there was something about the Studebakers of the early fifties that captured Ian Fleming’s imagination. Although Fleming was not a gun enthusiast, as is evident by some of the firearm and holster choices he makes for Bond, he was certainly a car enthusiast. The Studebaker’s had developed something of an aura of being a cut above many other American cars, whether that was a justified perception or not, down in Australia the Studebaker Lark and later Cruiser were well regarded by police departments and often used as unmarked police cars in the state of New South Wales. But by the time we arrive at the early sixties Studebaker was a company in trouble, trouble of sufficient depth that even their merger with prestigious car maker Packard was not going to save them.

When the stakes are high simple optimism is not a good thing, but fatalism is fatal. Once when I was visiting a school classroom I was intrigued to see a poster on the wall which read “If you say ‘I can’t’ your mind gives up, but if you say ‘How can I’ your mind immediately starts working on a solution”. What Studebaker needed was someone who was a “How can I” person. They got that person in the form of ex-US Marine and savior of the McCulloch Motors Corporation Sherwood Egbert. Sherwood Egbert’s brief on becoming President of the merged Studebaker-Packard Corporation was to diversify the company’s interests in order to save it although not as a car company. The board at Studebaker-Packard was saying “we can’t”. US Marines are not taught to think “we can’t”, and so Sherwood Egbert got stuck into some “how can we” thinking and sketched out some ideas on a flight from Chicago.

Sherwood Egbert’s plan was to get the best design team the United States could muster and to create a new model Studebaker that would save the car brand. Egbert went to Raymond Loewy and got his formidable team onto “how can we” problem solving. Time was of the essence. The board at Studebaker would be near certain to say no to any proposal to create a new car so the design and a bullet proof feasibility proposal were to be created in secret and in a ridiculously short period of time. Why would Egbert be so confident that a new model Studebaker, a sports car, would bring people flocking back into Studebaker showrooms? The year was 1961, Jaguar released their E type or XKE as it was known in the United States that year and it set the motoring press ablaze, even Enzo Ferrari called it “The most beautiful car ever made”. This was a second time around for Jaguar, they had previously set the motoring press ablaze back in 1948 with their XK120. In both cases Jaguar had used a beautifully designed sports car as a publicity vehicle. Sherwood Egbert’s strategy for Studebaker was exactly that, to get America’s most renowned industrial designer to create a sports car that would fire the imagination of the motoring press and raise the Studebaker banner high in the automotive world.

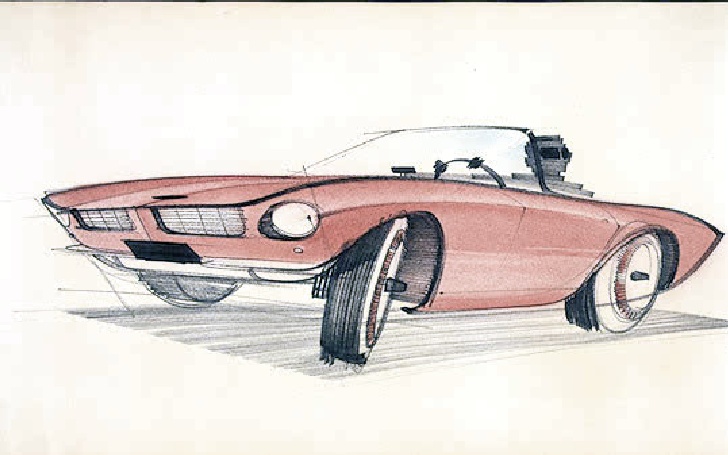

Egbert was determined to show the new sports car at the 1962 New York International Auto Show and that meant he and his team needed to go from idea to finished product in thirteen months. Raymond Loewy was given just forty days to create the design and it needed to be done away from prying eyes at Studebaker. So he rented a house in Palm Springs and took three trusted designers with him, Bob Andrews, John Ebstein and John Kellogg. For the team the design brief was to create something a bit like the Jaguar XKE, a car that was beautiful and a car that was a complete break away from the jukebox style chrome and fins that had been the hallmark of American cars of the fifties and early sixties.

In one week Loewy’s design team had created a design including drawings and a three dimensional eighth scale clay model. We suspect that they were working rather longer hours than “nine to five”. Not wishing to show Sherwood Egbert the design on April Fools Day they revealed the design on April 2nd and got his approval. At that stage the design team moved to the Studebaker factory at South Bend and had their full size clay model completed by April 27th. At that time the car was given it’s name which needed to be exotically continental and suggestive of speed. They chose the name Avanti, which is Italian for “forward”.

The Avanti was not going to be the technological marvel that the Jaguar E type was however. The E type had been created over a period of years by a company that had gained its design experience in motor sport, experience that included no less than three wins at the 24 hours Le Mans race. Everything about the E type had been literally race proven. The Studebaker Avanti was to be in production in one year and so it had to be built onto something Studebaker already had in production, and that was the Studebaker Lark. The Studebaker Lark chassis, engine and drive train were not in the same league as the E type but it was going to be possible to create an American as apple pie muscle car on that chassis and to do some impressive things with it.

The practical decision was to put the Studebaker 289 cu in V8 into the Avanti with the option of a four speed manual or three speed Borg Warner automatic. The engine was given a thorough updating and in its final form was churning out a respectable 240hp. This was sufficient to accelerate the car from standing to 60mph in 9.5 seconds which put it on a par with the British Austin-Healey 3000 and the Ford Thunderbird. Not content with that however it was decided to offer a supercharged V8 version and that would accelerate from standing to 60mph in a brisk 7.5 seconds and keep right on going to a top speed of over 120mph. The only American cars that would keep up with that were the Shelby Cobras or a tweaked up Corvette Stingray.

The Avanti was to be a publicity vehicle so it was important to establish some “street cred” with it and what better place to do that than the Bonneville salt flats? In 1962 as the model was launched a somewhat sorted out supercharged Avanti was taken to Bonneville where it achieved an impressive 171mph. That’s not too bad an effort from a car built on a Studebaker Lark chassis. Later a special car was prepared with twin superchargers and that managed an eyeball stretching 196.62mph USAC certified.

The design team understood that it was going to be really important to make the Avanti stop efficiently as it was capable of top speeds similar to the Jaguar XKE. Eleven and a half inch Bendix disc brakes (made under license from Dunlop of Britain) were fitted at the front and eleven inch finned drums at the rear. So with its aerodynamic wedge shaped front end and nose down attitude creating stabilizing down-force on the car at speed and an excellent braking system this car was made to be safe and stable when driven fast. Being built on a Studebaker Lark chassis however the car’s handling was never going to match the race bred Jaguar XKE.

Because of the hurried time frame in which the Avanti was to enter production it was impossible to make the bodywork of steel. So it was decided to make it of fiberglass and that work was subcontracted out to a company called the Molded Fiber Glass Body Company. Fiberglass was already being used by a number of limited production sports car makers such as Lotus Cars in Britain so it was a natural choice and a good fit with the overall concept of the car. The car body has some innovative safety ideas incorporated in it including an integral roll bar in the roof.

Problems with production and illness striking Sherwood Egbert worked together against the Studebaker Avanti however and because of those problems it was unable to be the savior of Studebaker cars. The Avanti was such a good car however that two men, Nathan Altman and Leo Newman, went to Studebaker shortly after production of the Avanti ended in 1964 and bought the dies and the rights to the car. They modified the design a little and put it back into production as the Avanti II. The Avanti II continued in limited production in various hands right up into the twenty first century. Raymond Loewy himself purchased an Avanti II in 1972, he really believed in the car.

The white 1963 Studebaker Avanti featured in our pictures is coming up for sale by RM Sotheby’s at their Motor City auction to be held in The Inn at St. John’s, Plymouth, Michigan on Saturday 30th July 2016.

You will find the sale page for this car if you click here.

The Studebaker Avanti is a car that I think Ian Fleming would have felt completely happy about having James Bond drive in his American adventures in “Live and Let Die“. It is an all American car created by a design team led by the most famous American industrial designer of the twentieth century, Raymond Loewy, to fulfil a vision held by a never say die ex US Marine named Sherwood Egbert.

(All pictures except the original Raymond Loewy sketch courtesy RM Sotheby’s).

Jon Branch is the founder and senior editor of Revivaler and has written a significant number of articles for various publications including official Buying Guides for eBay, classic car articles for Hagerty, magazine articles for both the Australian Shooters Journal and the Australian Shooter, and he’s a long time contributor to Silodrome.

Jon has done radio, television, magazine and newspaper interviews on various issues, and has traveled extensively, having lived in Britain, Australia, China and Hong Kong. His travels have taken him to Indonesia, Israel, Italy, Japan and a number of other countries. He has studied the Japanese sword arts and has a long history of involvement in the shooting sports, which has included authoring submissions to government on various firearms related issues and assisting in the design and establishment of shooting ranges.