Frenchman André Chapelon is arguably the greatest railway steam locomotive engineer and designer the world has ever seen. Whereas others are known for individual designs and creation of items that improved steam locomotive efficiency André Chapelon took a holistic approach to steam locomotive design applying an extensive understanding of the science required. The end result was that his locomotive designs were so efficient that French railway bureaucrats were worried that he was creating steam locomotives that were more efficient than the electric ones they wanted to “modernize” to. As a result none of André Chapelon’s original designs were allowed to go into full scale production, and all of his prototypes were scrapped and destroyed. Only some of the locomotives he modified and improved remain extant today as a legacy of what might have been.

The secret to André Chapelon’s success lays not so much in him trying wildly new ideas as it is in his use of science and a high level of technological attention to detail to optimize existing technology. Chapelon’s work was about refining and tuning in the same way that the designer of the engine of a Formula 1 car uses existing internal engine technology but refines it to produce extraordinary results. Externally his steam locomotives look conventional – but the fine tuning that lays hidden beneath that ordinary looking exterior really showed the potential of steam as a motive power.

André Chapelon was born on 26th October 1892 the great grandson of an Englishman who had migrated to France in 1812 to teach the French steel forging. Upon leaving school he enrolled at the École Centrale Paris but his education was interrupted by the First World War (in which he served as an artillery officer). In 1919 after the war’s end he returned to school and graduated as an Ingenieur des Arts et Manufactures in 1921. After graduation the young André got a job with the Paris à Lyon et à la Méditerranée railway company (PLM). Although his job with the PLM was with locomotives and rolling stock Chapelon realized that the job was going to be a dead end so he left there in 1924 and worked briefly for the Société Industrielle des Telephones before moving on again to work with trains, which was his passion, this time with the Paris à Orléans railway (PO) in 1925.

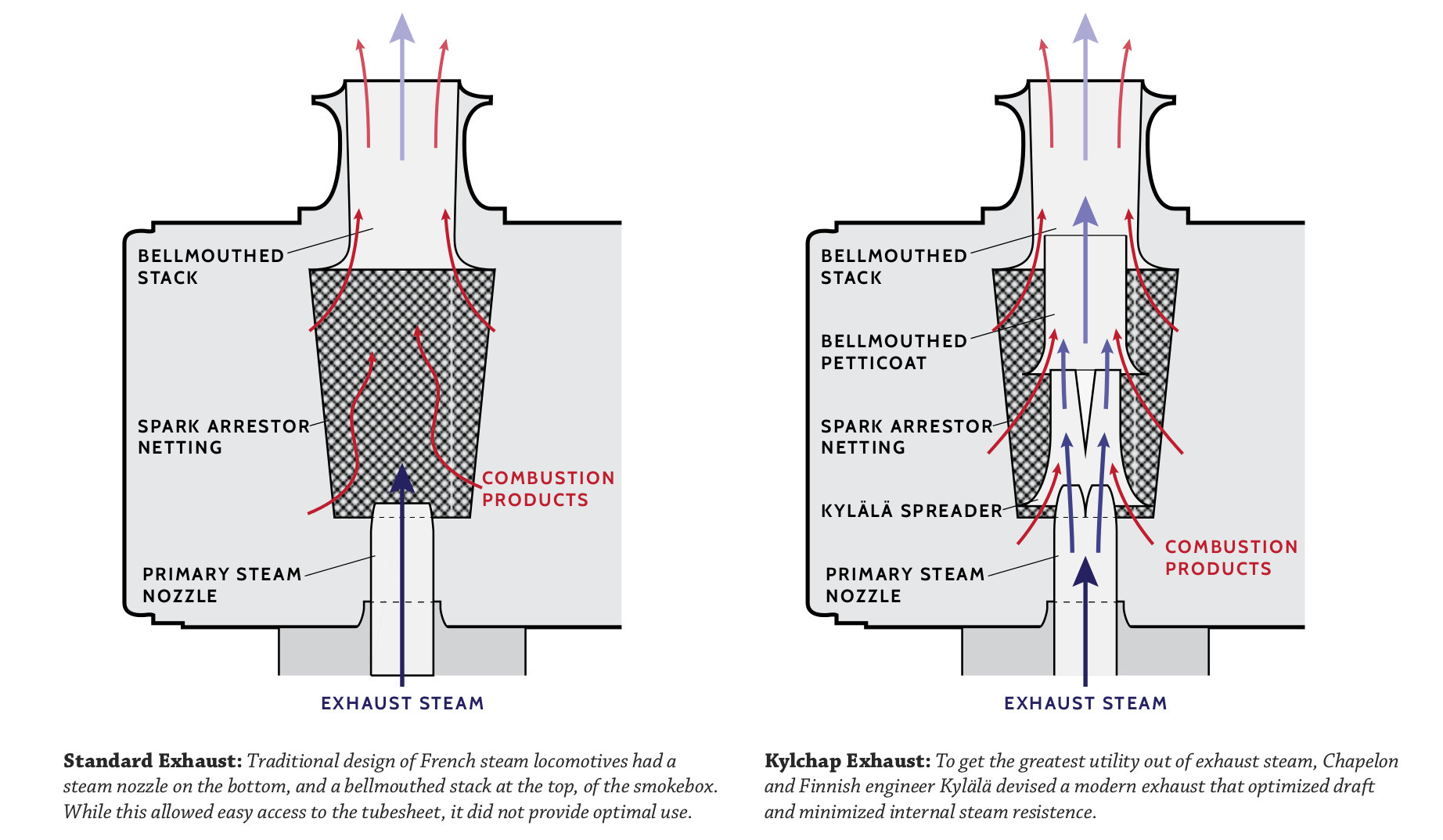

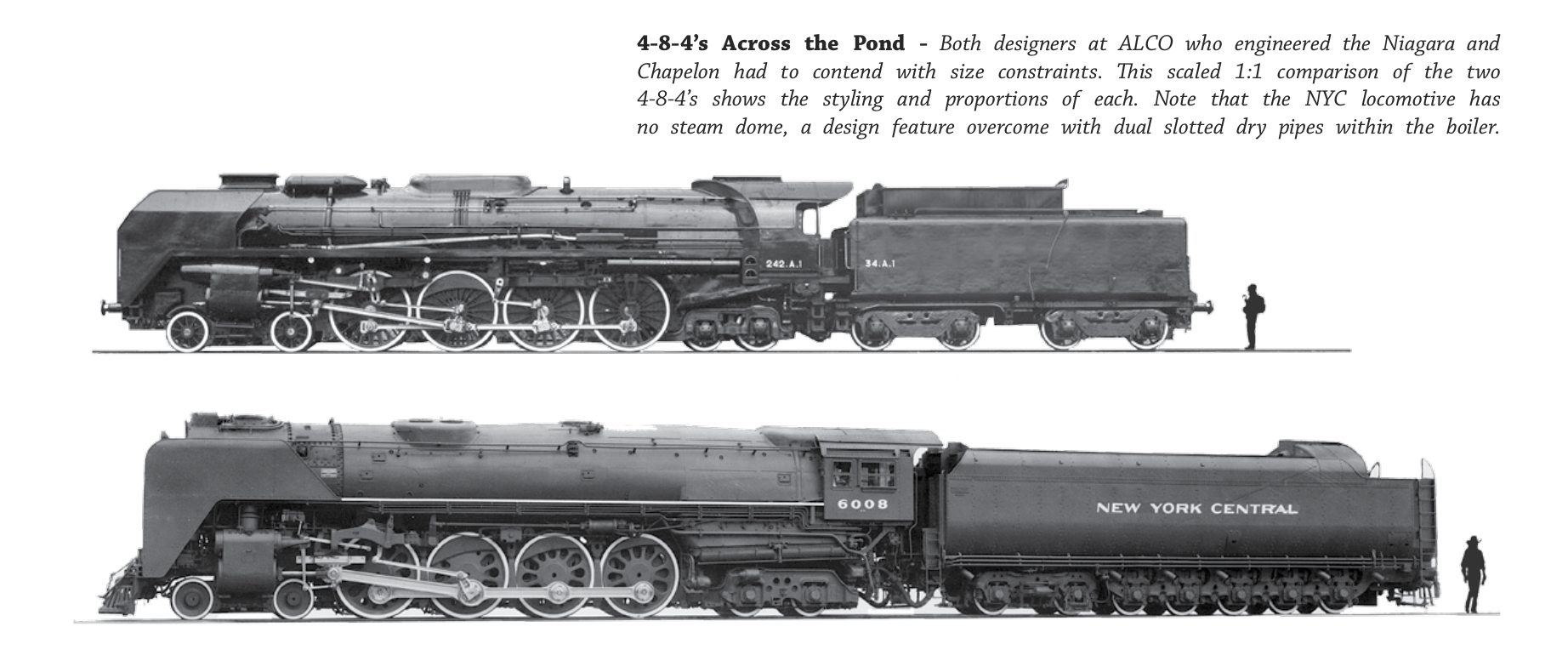

André Chapelon’s first major invention which he jointly created with Finnish engineer Kyösti Kylälä was the Kylchap exhaust for steam locomotives. The name Kylchap comes from the names of the two engineers Kylälä-Chapelon. After this the Paris à Orléans railway had Chapelon re-build an old 4-6-2 Pacific passenger locomotive number 3566 which proved successful and surprised many with what he’d achieved. This led to his being allowed to re-design other existing locomotives in the twenties and thirties. The Kylchap exhaust system is one of few of Chapelon’s innovations that found its way into American steam locomotives. Interestingly the only American locomotive designer who studied and incorporated some of André-Chapelon’s innovations was Paul Kiefer of the American Locomotive Company (ALCO) in his design of the New York Central’s S1 and S2 Niagara.

In 1934 André Chapelon received a number of awards for his work on steam locomotives including being made a Chevalier of the Legion of Honour, the Gold Medal of the Societe d’Encouragement pour l’Industrie Nationale, and the Plumey Prize of the Academie des Sciences. In 1938 he published his definitive work “La locomotive a Vapeur” (The Steam Engine). You can find this book on Amazon with English translation if you click here.

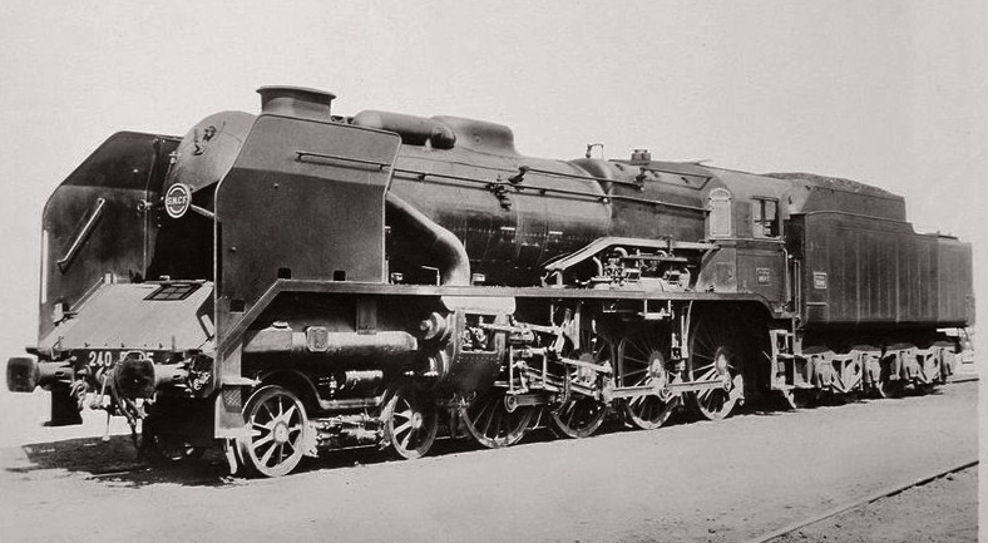

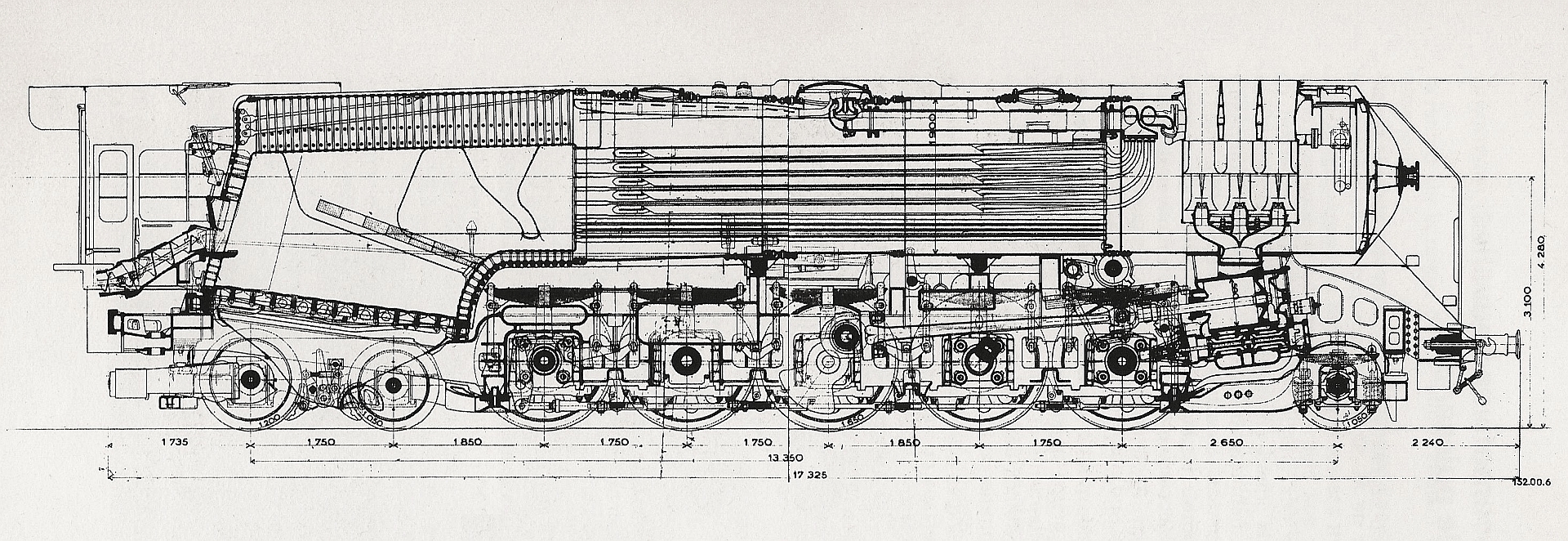

The last steam locomotive constructed on an André Chapelon design was his 242A1 which was built in 1950. This was a three cylinder compound 4-8-4 “Northern” (or “Niagara” as the New York Central would have called it). This locomotive incorporated the streamlining of steam pathways, Kylchap exhaust and three cylinder compounding to create a heavy passenger engine without peer. Producing 5,300hp and a mean tractive effort of 46,255 lbs it painted a picture of the future of steam locomotive power that was arguably more efficient than comparable electric motive power. This being seen if you make the comparison fair and include the energy losses from the coal fired steam generated electricity from the power station to the wheels of the train. Chapelon showed that his 242A1 translated the coal energy directly and with less loss than the coal energy translated into electricity and then sent along power lines and through and electric motor to the rails. But the rail bureaucrats were not interested in that, they wanted “modern” looking electric trains despite the losses and the 242A1 was quietly scrapped. This is sad because it was perhaps the greatest steam locomotive the world had ever seen and deserved a place in the French National Rail Museum at least.

André Chapelon designed a modern generation of steam locomotives prior to his retirement. None of them were built but detailed drawings exist. It seems improbable that any of them will one day be translated from paper into steel but then the work of visionaries is rarely allowed to see the light of day. Chapelon passed away in 1978 but his legacy lives on in trains even today. He was consulted on the design of France’s new generations of electric locomotives and technology he developed is used in the high speed TGV trains we have with us today. But above all André Chapelon loved steam locomotives and the romance of steam. He was French after all – romance was in his blood.

Jon Branch is the founder and senior editor of Revivaler and has written a significant number of articles for various publications including official Buying Guides for eBay, classic car articles for Hagerty, magazine articles for both the Australian Shooters Journal and the Australian Shooter, and he’s a long time contributor to Silodrome.

Jon has done radio, television, magazine and newspaper interviews on various issues, and has traveled extensively, having lived in Britain, Australia, China and Hong Kong. His travels have taken him to Indonesia, Israel, Italy, Japan and a number of other countries. He has studied the Japanese sword arts and has a long history of involvement in the shooting sports, which has included authoring submissions to government on various firearms related issues and assisting in the design and establishment of shooting ranges.