The story of the “Around the world by Grizzly Torque” expedition began back in 1956 and was first inspired by a young biology master’s degree graduate of the University of Toronto, Canada. His name was Bristol Forster and having spent the preceding twenty years in school and university he had a desire to go on an adventure and see the world: and the best way to accomplish that was, in his opinion, to drive around the world.

Fast Facts

- Bristol Forster and Robert Bateman decided to do an around the world journey in 1956 and successfully made that trip in 1957.

- The vehicle they chose for their trip was a Series 1 Land Rover fitted with a modified ambulance custom body made by Pilchers in Britain.

- The journey took fourteen months and covered approximately 60,000 kilometres.

- Both Bristol and Robert were deeply interested in natural environments and the creatures that inhabited them: Bristol as a biologist and ecologist, and Robert as an artist.

- To the end of experiencing as much of the things that fired their interests the two young men planned to visit places that were predominantly wild and minimally affected by human settlement and industry.

- The custom Land Rover they used was discovered in poor condition decades after their journey and has been thoroughly restored. It is coming up for sale by RM Sotheby’s at their Monterey sale 17-19 August 2023.

Perhaps he’d read Jules Verne’s “Around the World in Eighty Days” in his younger days: or perhaps he’d seen the movie that starred British actor David Niven and Mexican Mario Fortino Alfonso Moreno Reyes (who’s stage name was “Cantinflas”). The movie made its debut in 1956 – the year that planning for the Grizzly Torque adventure began.

Whatever the inspiration Bristol Forster came from a family who were both financially able to help young Bristol achieve his vision, and who were well connected in international business and thus able to give him letters of introduction to influential people in many of the countries he would visit.

Bristol Forster’s passion was wildlife and especially Arctic animals and their habitat. For his master’s degree he had made a study of a rare lemming like mammal, and his passion for wildlife would be life-long.

Bristol’s close friend was Robert Bateman. The two had been friends at school, both being members of the Nature Club at the Royal Ontario Museum, and remained friends in the years after that. Robert was at that time working as a teacher of art, and of geography. Art was already the primary focus of his life and it would remain so.

Robert’s passion was for the natural world and the creatures that formed an integral part of it: he would go on to become one of Canada’s preeminent painters.

In 1956 he had a steady job, a steady income, and like most young men in the 1950’s was looking for the right young lady to marry and begin a family with.

In the 1950’s when Frank Sinatra sang “Love and marriage, love and marriage, go together like a horse and carriage. This I tell you brother, you can’t have one without the other.“ That summed up the zeitgeist of the time.

For Robert the right young lady had not yet come along, so when he got a phone call from Bristol suggesting that they could embark on a bit of an adventure it piqued his interest, and that adventure was to drive around the world: that would surely provide some fascinating stories to tell his children and grandchildren. Not only that but it promised to be a mind opening experience that could inspire and feed his passion for painting wild places and wildlife.

Given their joint passion for the natural world Bristol and Robert were a natural team: two young men who would greatly benefit from travel to wild places and all the enrichment that would bring into their lives.

Preparation Precedes Blessing

Thus it was that the two met up and starting rough planning how they would like to go about their expedition. There was a world map in an old school atlas and they began to bounce ideas off each other looking at that.

The young men reasoned that if they wanted to go somewhere adventurous that would bring them into places where wild animals, birds and habitat would be truly fascinating then the best place to start was Africa. Both Bristol and Robert were fascinated by Africa’s wildlife and wanted to be able to spend time seeing Africa’s wild animals in their natural habitat.

That being said they had to be cautious about where in Africa to go. The post-war era was a time when the African states that had been colonized were seeking freedom and self-government. Things were taking a violent turn in South Africa and East Africa among others and communist revolutionaries were active in many places across the continent.

In East Africa for example the “Mau Mau” were engaged in a violent campaign to remove the colonialists from Africa and bring in “Uhuru” (i.e. “freedom”), and if Bristol and Robert found themselves in a close encounter of the Mau Mau kind then their adventure could come to a sticky end: a prospect best avoided.

From Africa Bristol and Robert wanted to travel to India, and drive up into Nepal, and then to Malaya (modern Malaysia), and Thailand.

From there travel to the wild bush-lands of Australia and a journey ending in Sydney, and then home to Canada.

It looked like they had their vision plotted out, it was at that point time to do the detail planning and preparation. The pastor of a church I attended years ago often said “Preparation precedes blessing”, which is common sense, you can only expect success if you do your due diligence and prepare effectively.

Bristol and Robert were helped in their planning and financing by Bristol’s father in particular. He told the guys that they would need to contribute $2,000.00 Canadian dollars each and take photographs and movie film footage of their journey, and document it with written accounts of their travels.

The two young men were invited to submit accounts of their journey to the Toronto Telegraph which then carried regular articles detailing the journey and events along the way.

Robert would put his artistic talents to good use with drawings, which included some small vignettes that would adorn the sides of the vehicle they used for the journey.

Its important to put things into a 1950’s perspective for this journey. These were the days when there were no satellite phones, no digital cameras nor video cameras, and no computers with convenient word processor software.

There was no e-mail, and an urgent message could only be sent if one got to a town with a post office, and that post office needed to be equipped with a telegraph connection so it could transmit and receive telegrams. These were sent by Morse code and had to be short and succinct.

Bristol and Robert were going to be traveling in places that were remote. They were going to have to be highly self-reliant, and their families wanted to be sure they knew as far as possible where they were so that in an emergency they had the best chance of getting help for them.

Instead of a digital camera the guys had a film camera: one of those old-fashioned ones that has to have film put into it, and then the film has to be developed in a darkroom with chemicals to get prints. The maximum number of pictures one could get from one roll of 35 mm film was thirty six.

Instead of a video camera they had a 16 mm film movie camera, and just like the still camera the 16 mm film had to be taken to a laboratory where they could process the movie film with chemicals to develop it and make it suitable for projecting with a 16 mm film projector.

These 16 mm film cameras were typically driven by a mechanical clockwork mechanism and did not need batteries. They usually required the use of a light meter such as the Weston with which to figure out the exposure settings – the aperture settings – so the filming was done allowing the correct amount of light onto the film.

The 16 mm camera did not have sound recording, that normally had to be done on a tape-recorder and added to the film at the processing laboratory later: and if you are reading this and thinking that it sounds like hard work, and expensive, then you are right on both counts.

Bristol was primarily responsible for managing the filming and keeping the film organized. It would prove invaluable not only when the trip was taking place but also in recent years for the making of a video to commemorate the Grizzly Torque expedition by Land Rover for their 70th Anniversary.

Last but not least, instead of a laptop and word processor the guys had a typewriter, one of those lovely old manual ones that goes click clack and does not need to be plugged in.

Grizzly Torque Joins the Expedition

The major piece of equipment for this journey was the vehicle, and for Bristol and Robert there was only one choice worth considering, and that was a Land Rover. In the areas where the guys planned to travel the Land Rover was by far the most common vehicle and its four-wheel-drive capability was going to get a lot of use.

The Series 1 Land Rover had been designed from the ground up to be not only reliable but also owner fixable. It was made so that it could be completely pulled apart in primitive conditions and put back together again.

As a part of their preparation Bristol went to the Land Rover training school and learned how to pull the entire vehicle apart and put it back together again so he knew what tools and spares to take, and had the hands on experience of using them.

To be suitable for the around the world journey the Land Rover needed to be fitted out so Bristol and Robert could live in it. When parked in the African bush they needed to be able to sleep in it to remain out of harm’s way from hungry carnivores and the insects and such-like creatures that could cause horrible diseases.

They chose a long wheelbase Land Rover fitted with the custom ambulance body which was made by British custom coachwork maker Pilcher for Land Rover. This provided two bunks for sleeping or resting on and space in which to get their daily accounts of their journey typed up.

This Land Rover ambulance was modified to provide an opening roof so it could be used for observing and filming wildlife in whatever country they happened to be in. It would also be a great feature for star gazing.

It was also fitted with a reinforced aluminium luggage plate for carrying gear such as a shovel and rope.

The Series 1 Land Rover was purchased with an optional capstan winch which was different to the style of winches we find on four-wheel-drive vehicles nowadays. It was used with rope with the operator feeding the rope around the capstan and maintaining tension on it to help it grip and pull the vehicle out of whatever muddy, slippery situation it was in. This winch would get quite a bit of use on the journey.

Bristol and Robert decided to dub the Land Rover “Grizzly Torque”, and they labeled the Jerry Cans that were carried in brackets mounted on the bumper and front fenders “Gin & Tonic”.

Gin and Tonic was the iconic drink of the British Empire, although the Jerry Cans were not filled with the stuff but with whatever grade of gasoline/petrol could be found.

The Land Rover engine was made to be able to run on almost any fuel, including power kerosene, but it might have struggled to run on Gin. (That being said there was once a car created that could run happily on Tequila and so it could have managed Gin also).

The Adventure Begins

With the Grizzly Torque delivered and fitted out Bristol and Robert took it for a bit of a shake-down expedition up into Scotland so they could be confident that there were no apparent issues with the car, and so they could get familiar with it. It had been agreed between them that Bristol would do the driving and mechanical work needed and that Robert would take charge of the food and cooking. It was an arrangement that worked out well. Robert was reluctant to drive Grizzly Torque as it had been purchased by Bristol’s father and he didn’t want to run the risk of damaging it in an accident.

Grizzly Torque was loaded onto a cargo ship early in 1957 and set sail for Ghana on Africa’s west coast. There Robert and Bristol began the African stage of their around the world adventure.

They headed inland to Nigeria, the Cameroons, and then into French Equatorial Africa. The next stage took them into the Belgian Congo where they encountered people of the Forest Pygmies who were friendly to them and whose company they greatly enjoyed.

Some of these pygmies of the Mbuti decided that they would like to join Robert and Bristol for a drive along the jungle tracks and so between two and three dozen piled aboard and off they went with Bristol at the wheel.

Of course being Africa the journey had to be accompanied with singing, and when Africans sing and harmonize it is delightful to listen to, and it happens with surprising spontaneity.

Saying their fond farewells to the Mbuti Robert and Bristol resumed their journey through Rwandaurundi, Uganda, Kenya, and finally Tanganyika. There were many opportunities to photograph, film and study the natural environment and the wildlife that filled it: Bristol and Robert have described it as an experience of complete freedom, a time when they felt more free than they had ever felt before.

At the end of their journey across Africa the pair made their way to the port city of Dar es Salaam where Grizzly Torque was loaded onto a ship for the journey to India.

Driving in India provided some challenges simply because of the population density and at one stage Bristol was forced to brake and swerve to avoid a person on a bicycle.

This incident necessitated such hard braking combined with a swerve that Grizzly Torque could not cope with the transfer of weight onto the front left side wheel and rolled onto her side, breaking the driver’s door window.

Fortunately the damage to Grizzly Torque was minimal, with the driver’s side door window broken. This was easily replaced with a suitably sized Perspex (i.e. plexiglas) plastic window and Robert and Bristol were able to continue their journey north up to Nepal, where they hoped to encounter a snow leopard and perhaps even photograph one.

The guys then moved to Nepal and Sikkim in the Eastern Himalaya. this area presented them with a vast range of biodiversity with both alpine and sub-tropical areas to appreciate and document.

The journey continued as planned through Burma, Thailand, and Malaya, ending in Singapore.

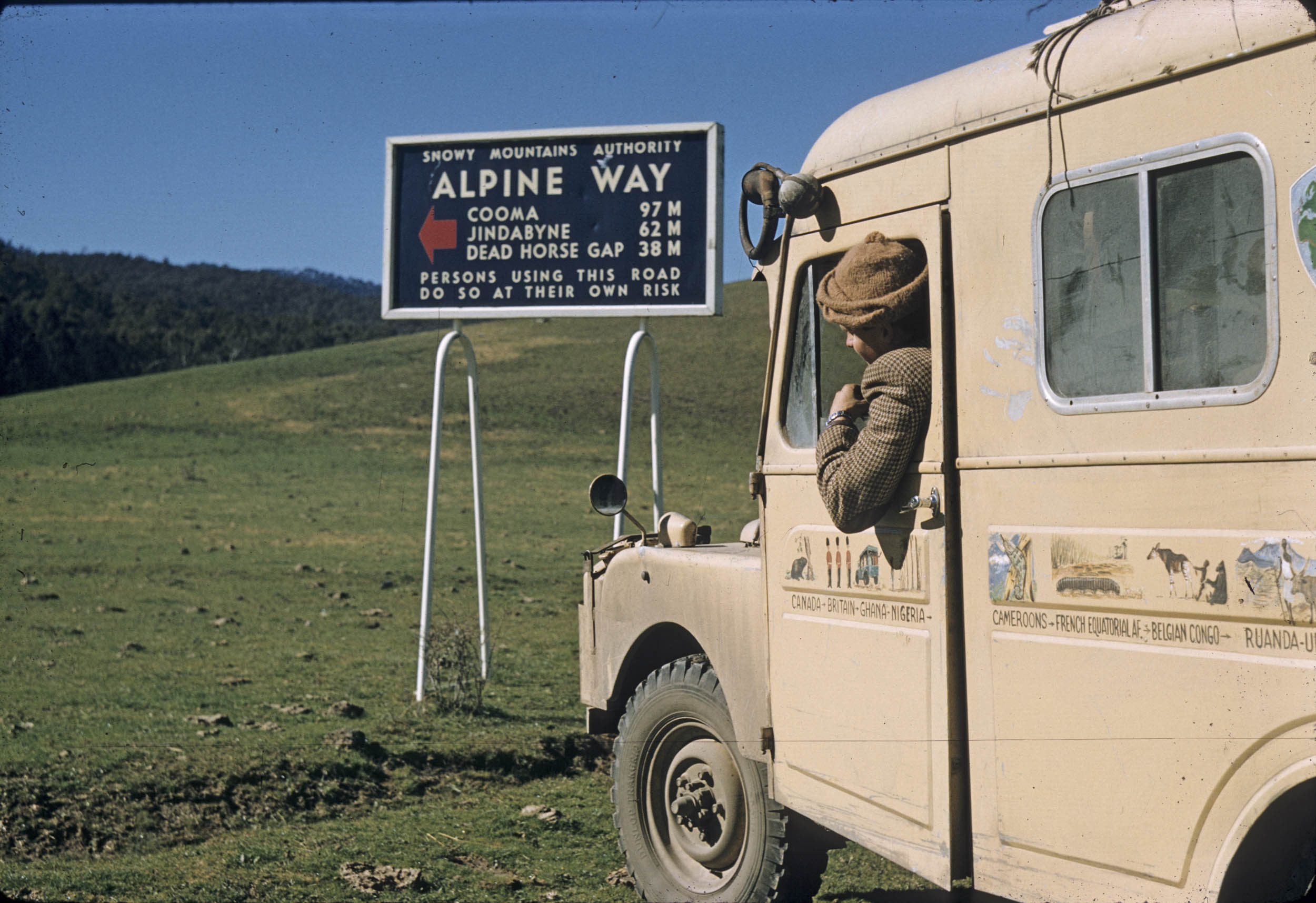

From there Grizzly Torque was off for a bit of a sea journey to Australia where the guys experienced the arid interior and made their way up into the Australian Alps.

At that time the construction of the Snowy Mountains hydro-electric scheme was underway, and Land Rovers were a backbone vehicle for the construction teams.

Near the small town of Jindabyne was the area where the ski resort of Thredbo was under construction in 1956 and 1957.

Then it was time to come down from the Australian Alps and make their way to the city of Sydney to load Grizzly Torque onto a ship for the final leg of the journey across the Pacific to Canada.

Grizzly Torque Forgotten and then Re-discovered

With their around the world journey over Bristol used Grizzly Torque as transport for a while after the return to Canada but it was not well suited to suburban driving, not exactly the most convenient daily driver. Its cruising speed was only 50 mph, and with the ambulance body rear visibility was quite poor.

So although it had been fitted with the optional heater/demister things like the lack of synchromesh on first and second gears and the overall agricultural nature of it persuaded Bristol to sell it on to a biology student who was studying the small species of pig called peccary.

For the student having a vehicle that could go pretty much anywhere, and one he could camp out of, was ideal. He also had a pet eagle and it rather liked being able to perch on the back of the front seats and travel in comfort.

Eventually the student also found that when he no longer needed the Land Rover it was time to sell it on and so he did. Grizzly Torque was sold an unknown number of times until she finished up parked behind a rancher’s barn with three other old Land Rovers.

Because the Land Rovers were parked in the weather outside the barn they of course deteriorated year by year until the rancher decided to get rid of them.

A Land Rover enthusiast named Stuart Longair heard about the quartet of Series 1 Land Rovers and although he only wanted one as a restoration project the rancher was adamant that it was to be all or nothing, and so Stuart took them all, and just focused his restoration energies on the one he wanted, ignoring the other three.

Those other three finished up being stored for Stuart Longair by his friend and Land Rover restorer Alan Simpson who kept them on his farm, and there Grizzly Torque languished for about ten more years.

It was quite by chance that Stuart Longair stumbled upon some information that grabbed his attention: it was an account of the Grizzly Torque around the world expedition and Stuart realized that he might just have that very Land Rover sitting at Alan Simpson’s workshop yard.

Because the unique paintwork of the Grizzly Torque had long since be scrubbed back and the vehicle painted sky blue instead its original identity had been hidden.

Stuart managed to get Bristol Forster to come and see if he could identify whether or not the run-down Land Rover ambulance was in fact Grizzly Torque. Bristol’s recognition of the car was immediate – the custom features and dents and dings all added up – and the driver’s window still had the Plexiglas window that had been installed after the crash in India.

Stuart decided he would commit to a full restoration of Grizzly Torque, and the work began.

Restoring the Grizzly Torque’s bespoke coachwork posed special challenges as things had to be made by hand. The Land Rover’s bodywork was made with an aluminium alloy called “Birmabright”, which was the same alloy used for the bodywork of Aston-Martin cars. To panel beat Birmabright it has to be correctly annealed otherwise it will crack from metal fatigue.

The search for parts was international – made much easier by the Internet and the ability to search globally from home.

Once completed Grizzly Torque was exhibited at a number of venues in Canada, not least was at the Robert Bateman Centre in Victoria. When he was traveling the world in Grizzly Torque Robert would never have suspected that one day there would be such a thing as a Robert Bateman Centre. Sometimes life gives us joy in things we would never have expected to happen.

Grizzly Torque is now to be sold again, this time as a fully restored piece of Canadian history. She has featured in the Land Rover 70th Anniversary celebrations as a prime example of the “Land Rover spirit” of the intrepid people who have used Land Rovers in all manner of exotic places and exotic adventures around the world.

We hope she goes to a home where she will inspire others to embark upon their own journey of a lifetime.

The RM Sotheby’s sale page for Grizzly Torque can be found here.

Picture Credits: Pictures of Bristol and Robert’s world trip courtesy Robert Bateman, and Bristol Forster, some pictures courtesy Jaguar Land Rover, pictures of the restored Grizzly Torque which is coming up for auction courtesy RM Sotheby’s.

Jon Branch is the founder and senior editor of Revivaler and has written a significant number of articles for various publications including official Buying Guides for eBay, classic car articles for Hagerty, magazine articles for both the Australian Shooters Journal and the Australian Shooter, and he’s a long time contributor to Silodrome.

Jon has done radio, television, magazine and newspaper interviews on various issues, and has traveled extensively, having lived in Britain, Australia, China and Hong Kong. His travels have taken him to Indonesia, Israel, Italy, Japan and a number of other countries. He has studied the Japanese sword arts and has a long history of involvement in the shooting sports, which has included authoring submissions to government on various firearms related issues and assisting in the design and establishment of shooting ranges.