Introduction: Science or Politics?

In the rush to “modernize” their rail system the French, like most governments in the world, were not just interested in obtaining more efficiency or more speed for their rail network. Appearances were far more important because politics depends on appearances, not performance. In the world today we see governments wanting to have electric railways, and even electric automobiles, on the argument that these are clean and do not cause pollution. What those promoting these ideas do not confess to is that the electricity has to be generated first, and then transported to the train or automobile that is going to use it. The electricity is of course normally generated by coal or nuclear power.

In popular culture we see this mentioned in the iconic movie “Back to the Future” in which the “Doc”, Doctor Emmett Brown, has built a time machine based on a DeLorean (“If you’re going to build a time machine you might as well make one with style“). To power his DeLorean time machine the “Doc” has ripped off some plutonium from a group of Libyan terrorists who wanted him to build them a bomb. When the Doc’s teenage friend Marty McFly finds this out he says to the Doc “Do you mean this sucker is nuclear?” to which the Doc replies “No, this sucker is electrical.”: thus making the point that the 1.21 Gigawatts of electrical power needed for time travel had to come from somewhere, in this case from stolen plutonium.

So, electric trains and electric cars create an illusion of being clean and environmentally friendly, and can do so because the coal or nuclear power station is hidden away somewhere else and people don’t think about where the power comes from, unless perhaps they took physics at high school and actually remember some of the stuff they were taught.

André Chapelon’s Steam Powered Science

French engineer André Chapelon was a visionary who came up against the phenomenon of politics versus science with the end result that his lifetime’s work was cast aside and his original designs never allowed to see the light of day. Born in 1892 Chapelon was the great grandson of Englishman James Jackson, and after he had served in the French Artillery during the First World War he graduated as an engineer from the École Centrale Paris, and worked for the Paris à Lyon et à la Méditerranée (PLM) railway, the Société Industrielle des Telephones, and then moved on to the Paris à Orléans (PO) railway in 1925.

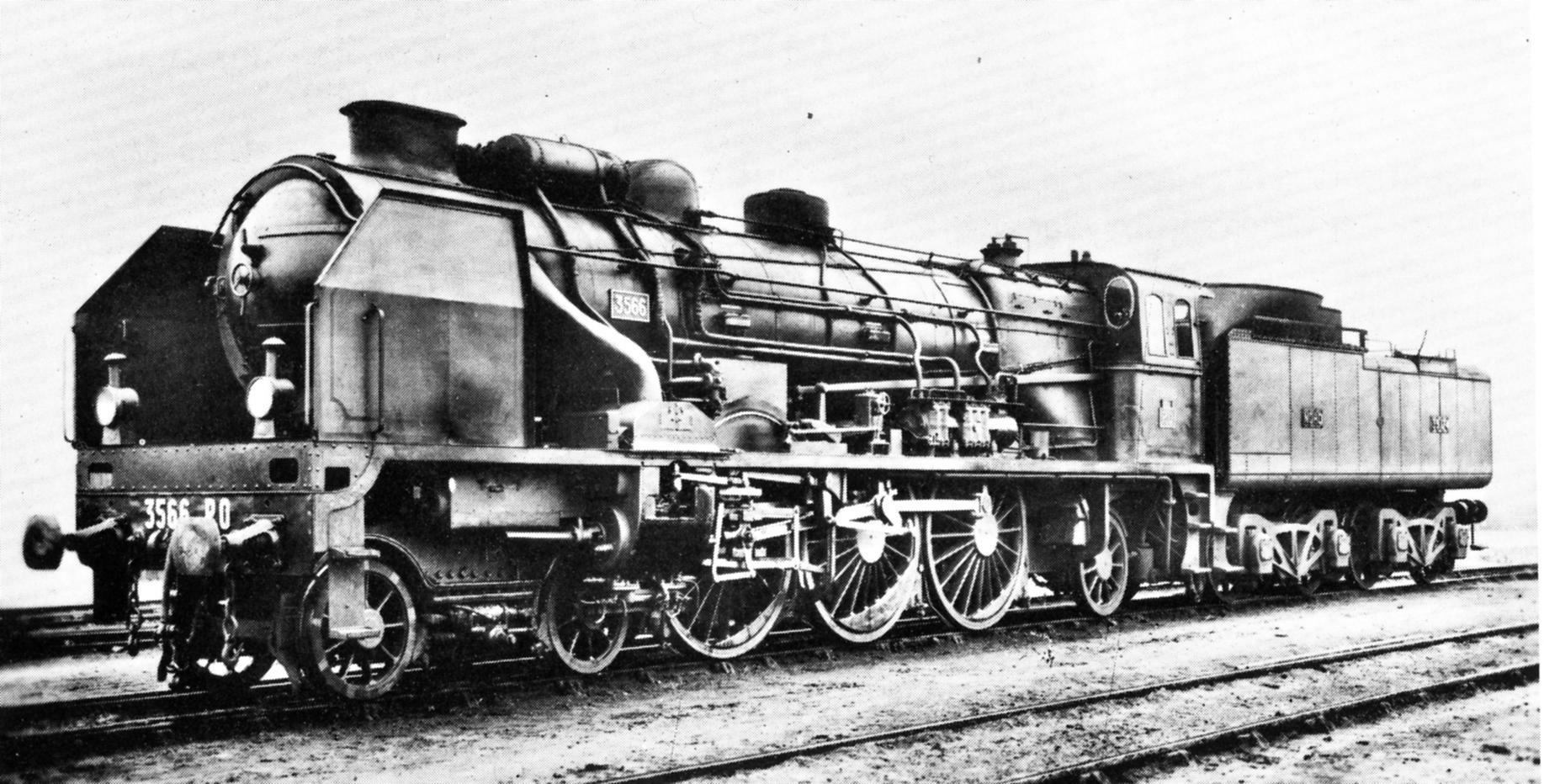

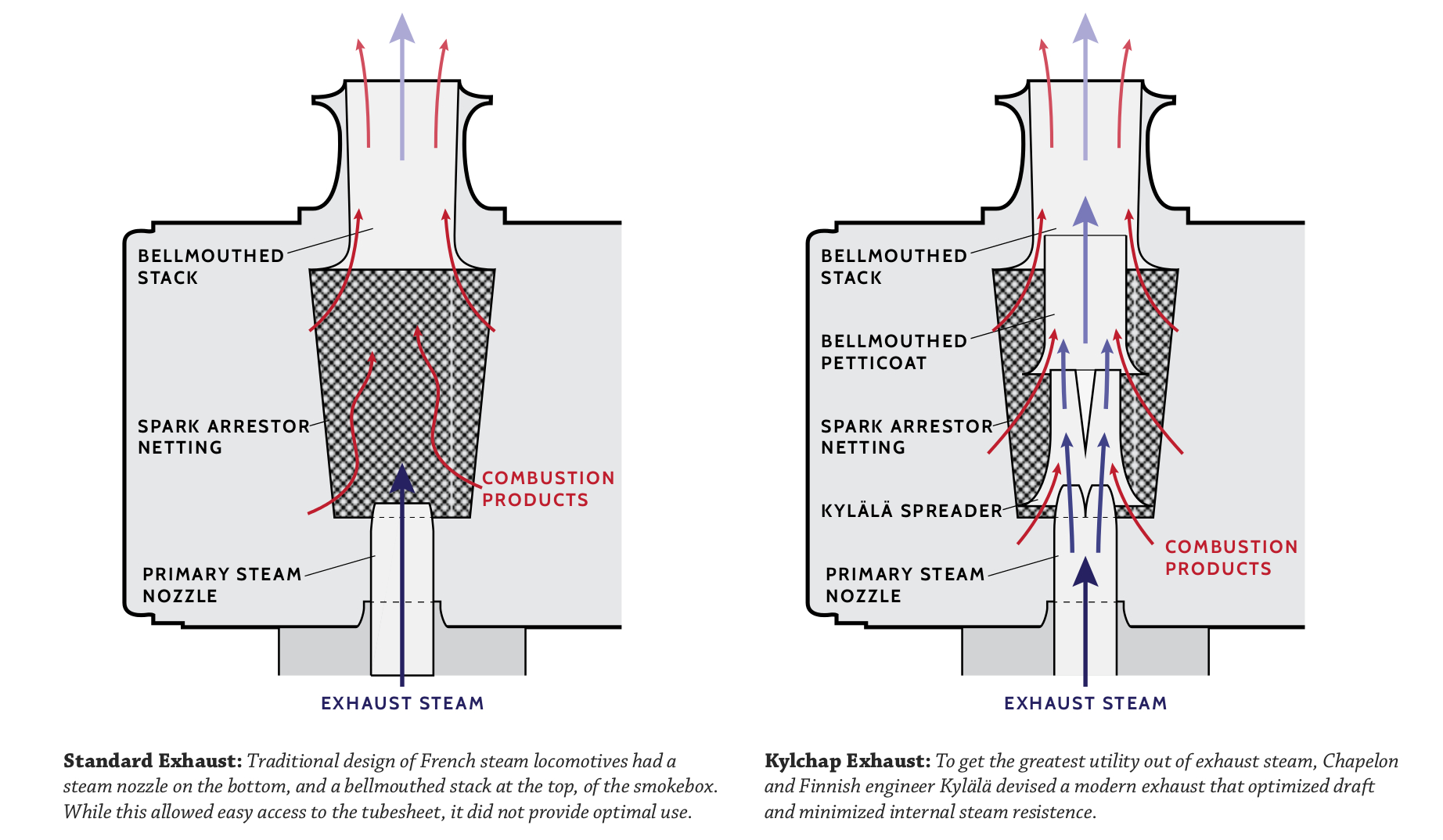

It was during his time at the Paris à Orléans railway that he got together with an engineer from Finland, Kyösti Kylälä, and between them they created the Kylchap (i.e. Kylälä Chapelon) exhaust system for steam locomotives, something that would feature in the ALCO designed and built New York Central Railroad’s Niagara locomotives. Not only that but Chapelon was charged with the task to design the rebuild of a PO locomotive No. 3566. Chapelon invested all his accumulated knowledge into that rebuild despite his peers not having any real expectation that his ideas would actually accomplish much. To their surprise the resulting rebuilt locomotive surpassed even their wildest expectations and Chapelon was given the job of doing redesign work on a number of other PO locomotives.

This next batch were Class 231F pacifics that had been originally been a de Glehn-Solacroup design. Chapelon started with the energy source, the firebox, and added 26.5 square feet of Nicholson thermic syphons to it. He increased the superheat from 300°C to 400°C and doubled the size of the steam passages. His redesign included the use of his Kylchap exhaust and he also added an ACFI feedwater heater. Last but not least was the change to poppet valves to maximize efficiency.

The results were exemplary. These locomotives were specifically used on the Poiters-Angouleme route which was undulating with many up and downhill grades. Because the French government had set a speed limit of 75 mph (120 km/hr) for steam locomotives this meant that these pacifics needed to be able to maintain as close as possible to the 75mph on the upgrades while not exceeding it on the downgrades. The Chapelon rebuilt locomotives happily did the 71 mile trip in one hour, and did it so reliably that the train schedule for that route was set at one hour.

This was the achievement that initially made André Chapelon’s name famous. He would go on to do a number of other rebuilds that proved to be great improvements over the originals.

Chapelon’s work was recognized and he was awarded Chevalier of the Legion of Honour, the Plumey Prize of the Académie des Sciences, and Gold Medal of the Société d’Encouragement pour l’Industrie Nationale. In 1938, just before the outbreak of the Second World War Chapelon published his most famous book “La Locomotive à Vapeur” (The Steam Locomotive) in which he outlined his methods and the science behind them.

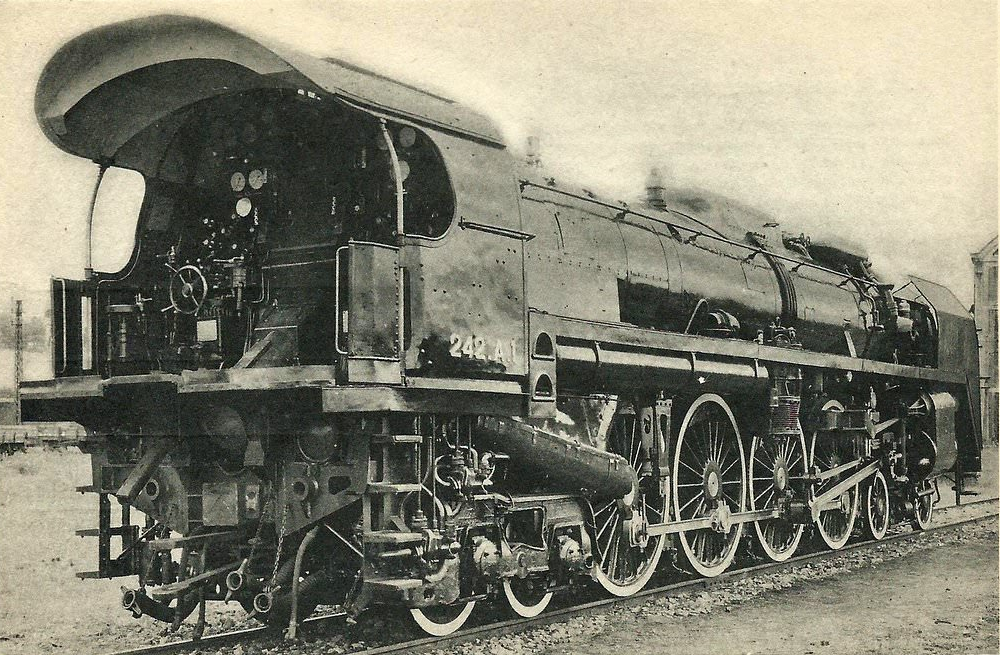

A Lemon Becomes a Powerhouse: Chapelon’s Last Rebuild, the 242A1

During the 1940’s while France was under German occupation André Chapelon worked on original designs that he hoped would be put into production once the war was over and the unwelcome Nazi visitors were sent back home again. It was in 1942 he was presented with what he hoped would be his opportunity to really demonstrate not only what he was capable of, but what efficiencies steam power was capable of. This opportunity came however in the most unlikely of packages. The locomotive he was given to redesign and rebuild was a three cylinder 4-8-2 “Mountain” type which had been prematurely withdrawn from service because it was not only inefficient but it had also been causing track damage. For Chapelon this was a bit like getting to the final and most difficult level of a computer game – except computer games hadn’t been invented yet.

Not only was this lemon of a locomotive going to be perhaps André Chapelon’s greatest challenge, but it also represented his greatest opportunity. Chapelon could see that in post-war France what would be needed was a standardized fleet of locomotives based around a common design. In Britain this was also understood and saw the creation of the British Railways Standard Class “Evening Star” and “Britannia” locomotives.

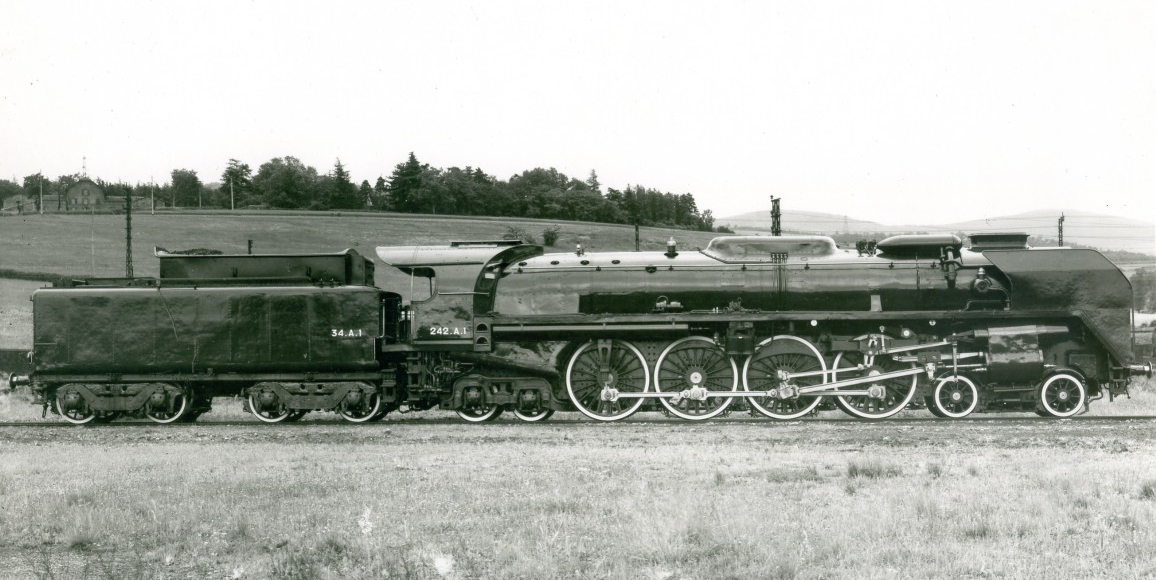

André Chapelon saw in the “lemon” locomotive the basis for the new French standard locomotives and proceeded to turn it into the first of what he hoped would be a fleet of both passenger and freight locomotives. The first problem to solve was how to get the power he was aiming for while keeping the original 4-8-2 within France’s 42,000lb axle loading. The answer was to add an axle into the design and make the locomotive a 4-8-4. The addition of the extra axle enabled Chapelon to incorporate the required frame reinforcing and provide the additional strength required in the leading crank axle.

The original 4-8-2 “lemon” had been built as a three cylinder engine and Chapelon kept to that layout but made the center cylinder the high pressure cylinder and the two outside cylinders the low pressure cylinders of a compound system. With the centrally mounted high pressure cylinder delivering power to the first axle the outside low pressure cylinders were set to drive the second driving axle and left and right were set at 90 degrees to each other with the center cylinder at 135 degrees. This set up provided for power and exhaust to occur at 45 degree intervals spreading the power smoothly throughout the wheel rotation.

The spreading of the power and exhaust in this way made for reduced stresses on the machinery and a more smooth draw for the fire. To ensure the best efficiency Chapelon used the first ever triple Kylchap exhaust to evenly cater for each of the three cylinders. The whole steam system was subjected to Chapelon’s careful attention to optimize efficiency. This level of attention to detail would pay dividends in the performance of the completed locomotive.

Not content with taking any half measured steps Chapelon removed the front truck and in its place installed an ALCO design with a roller centering mechanism. In the post war years there was collaboration between ALCO and Chapelon, and his Kylchap exhaust was used in their New York Central Niagara. For the rear truck a Delta type with rocker centering was fitted.

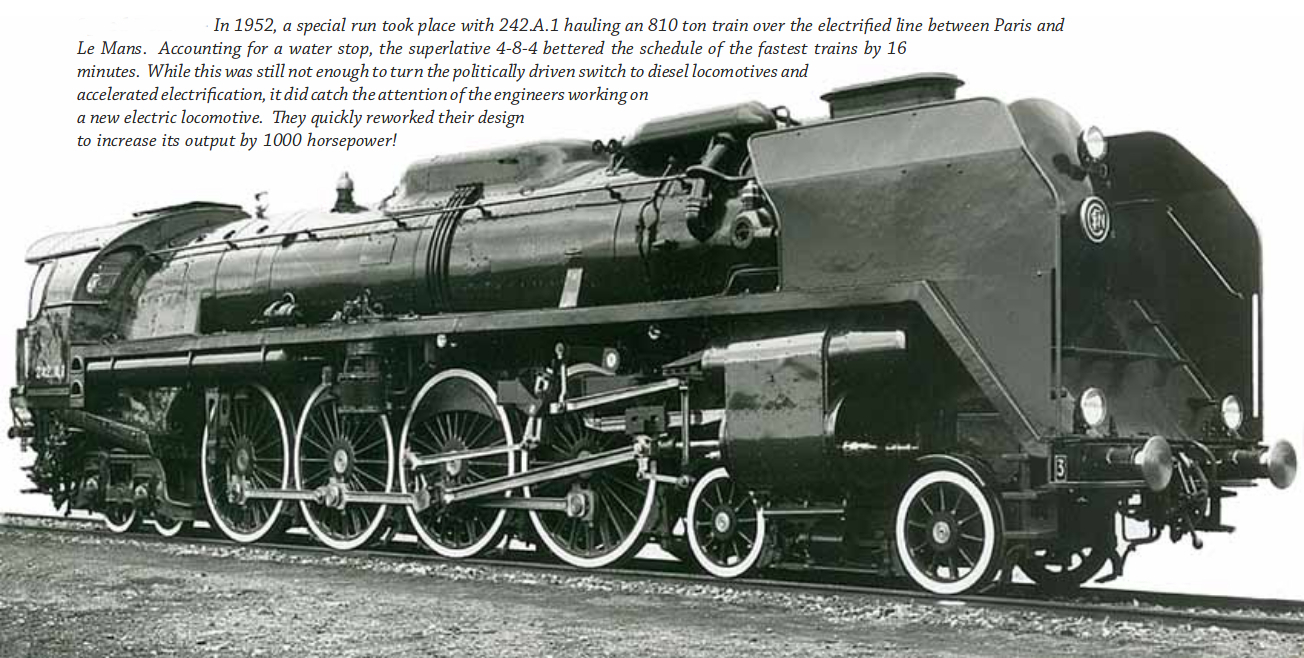

When the locomotive was complete it was a lemon no more but instead a smooth riding and graceful powerhouse providing 4,000hp between 50-63 mph with peak power of 5,500 hp. It was tested at speeds up to 94mph.

All of this was however insufficient to convince those in political circles to adopt Chapelon’s design, nor any of his other designs he had created. Instead the 242A1 was used for a period of years and then quietly scrapped, not even preserved at the National Railway Museum at Mulhouse. Chapelon and the 242A1 had been too successful for their own good, and the fate of the 242A1 was much like that of the ALCO built New York Central Niagaras, which were the ultimate American Railroad steam locomotives.

André Xavier Chapelon left an indelible mark on the history of the development of the steam locomotive before he passed away in 1978. His vision did not fit with the politics of the post-war era, despite his designs proving themselves often to be superior. Perhaps the lesson to be learned from Chapelon’s life is that no matter how good an idea is, if it does not fit with the political zeitgeist it is doomed to failure.

André Chapelon did his utmost to bring his vision into reality. He came very close to success, and certainly achieved design and engineering success.

(Feature image at the head of this post courtesy Wikimedia).

Jon Branch is the founder and senior editor of Revivaler and has written a significant number of articles for various publications including official Buying Guides for eBay, classic car articles for Hagerty, magazine articles for both the Australian Shooters Journal and the Australian Shooter, and he’s a long time contributor to Silodrome.

Jon has done radio, television, magazine and newspaper interviews on various issues, and has traveled extensively, having lived in Britain, Australia, China and Hong Kong. His travels have taken him to Indonesia, Israel, Italy, Japan and a number of other countries. He has studied the Japanese sword arts and has a long history of involvement in the shooting sports, which has included authoring submissions to government on various firearms related issues and assisting in the design and establishment of shooting ranges.