This is our most recent article for Hagerty Insurance of the UK. You will find this article on Hagerty Insurance’s web site if you click here.

Hagerty Insurance are a classic car insurance company. You will find their Classic Car Valuation Tool if you click here.

You can get a quotation from Hagerty Insurance for insurance on your classic car if you click here.

I wonder if you’ve ever thought about what it might be like to dine with the Devil? To the best of my knowledge no human being has ever actually done that, but Ferdinand Porsche and some of those who worked on fulfilling Adolf Hitler’s dreams of creating German superiority in motor sport, and in creating his Volkswagen came close, because they dined with Hitler on a regular basis.

Adolf Hitler was a car enthusiast. He didn’t have a driver’s license, he had chauffeurs instead, but he had a passion for cars. A bit like those who like to watch the football but don’t want to actually play it. In the nineteen thirties the world was emerging from the effects of the Great Depression, in Germany the effects of the depression had been particularly bad, exacerbated by the reparations she had been forced to pay under the Treaty of Versailles. But for classic car aficionados we need to understand the environment in which the classic German cars of the thirties were created, because it was the environment of Hitler’s Third Reich. Hitler was not interested in allowing the rest of the world to think they were the best at anything. He was interested in the world believing that the Germans were best at everything because he regarded the Germans as the “Master race”. Seen in this context the creation of the Mercedes-Benz and Auto Union racing cars that dominated motor racing in the thirties comes as no surprise. Hitler threw a lot of money at Mercedes-Benz, and less money but still lots of it at Auto Union and Ferdinand Porsche. It paid handsome dividends with the likes of Maserati, Alfa-Romeo and Bugatti finally meeting their match against the “Silver Arrows”, the Auto Union P-Wagen and Mercedes-Benz racing cars.

In this environment we can understand that the notion of “intellectual property” was not something Hitler was going to respect. In the creation of the Volkswagen for example Hitler encouraged two men to collaborate and share ideas, one was Dr. Ferdinand Porsche who is generally credited with designing the Volkswagen, and the other was Hans Ledwinka, an Austrian engineer who, like Ferdinand Porsche, had worked for Steyr in Austria but had then moved on to work for Tatra in Czechoslovakia whilst Dr. Porsche had set up his own automotive design consulting companies. In his work to design the Volkswagen Dr. Porsche freely admitted that he had met with Hans Ledwinka and “sometimes I looked over his shoulder, sometimes he looked over mine”. Between the two men and with assistance from other gifted engineers Hans Ledwinka created the Tatra V570 (which never entered production) and Ferdinand Porsche created the Volkswagen (which did). Hans Ledwinka also created the extraordinary Tatra T77 and T87. All of them aerodynamic, with rear engines using swing axles to create independent rear suspension, the Volkswagen and the Tatra V570 using a small air cooled horizontally opposed four cylinder engine. The Tatra T77 and T87 hanging an alloy V8 behind the rear axle, wonderful in a straight line but a car that would go into over-steer on steroids in hard cornering, and whatever you do don’t touch the brake if you’ve hit that corner too fast or you might find yourself doing a roly-poly into whatever happens to be in your way.

The management at Tatra were not impressed with Dr. Porsche’s collaboration with Hans Ledwinka and decided to sue the new Volkswagen company for patent infringement (The patents concerned were to do with air circulation and engine cooling, not the overall concept). Hitler quietly assured Dr. Porsche that he didn’t need to worry about the lawsuit, then Hitler invaded Czechoslovakia and solved the problem.

The Tatra T77 and T87 meanwhile became popular with top ranking Nazis such as Erwin Rommel, until it was noticed that quite a number of them finished up doing some involuntary inverted off-roading in their V8 Tatras, typically resulting in serious and sometimes fatal injuries. The Germans dubbed the big Tatras “The Czech secret weapon” and Hitler banned his senior officers from owning them so he wouldn’t lose too many more. Meanwhile Tatra were not allowed to make nice cars any more and had to make simple harmless trucks instead.

In amongst all of this Mercedes-Benz were looking at the technological innovations and the prevailing economic climate of the post Depression world and understood that their traditional market, the luxury and prestige car market, was shrinking. They realised that with the National Socialist Party in power and with that the vision of that political party for small and inexpensive cars so that Germany would go from being a nation where perhaps one person in fifty could own a car, to being a nation where most families could own a car to drive on the new network of Autobahns, there was a new market developing for less expensive, technologically innovative cars for this new era. Thus they decided to try creating their own cars using the unusual formula of a rear mounted engine with swing axles, and a sports version with a mid-engine with swing axles like the Auto Union P-Wagen racing cars. These creations were to become some of the rarest and most sought after Mercedes-Benz cars for modern day collectors, although in past years nice examples have sold at auction at quite reasonable prices.

The three rear engined Mercedes-Benz production cars of the thirties are the 130H, the mid-engine 150, and the Volkswagen look alike the 170H.

The Mercedes-Benz 130H (W23)

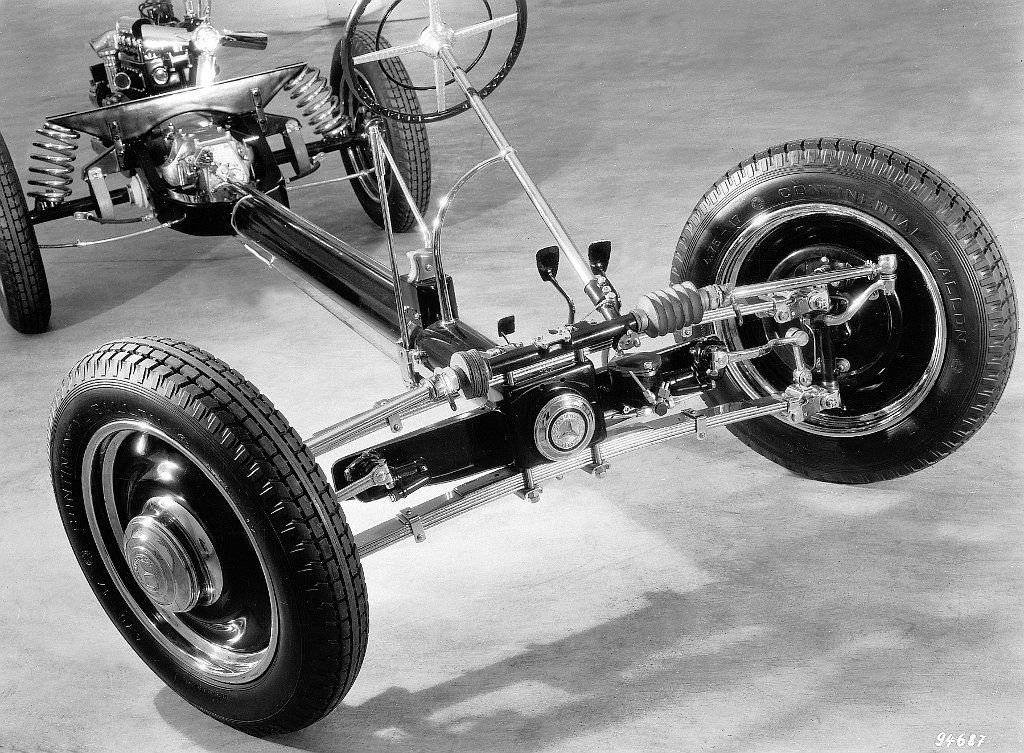

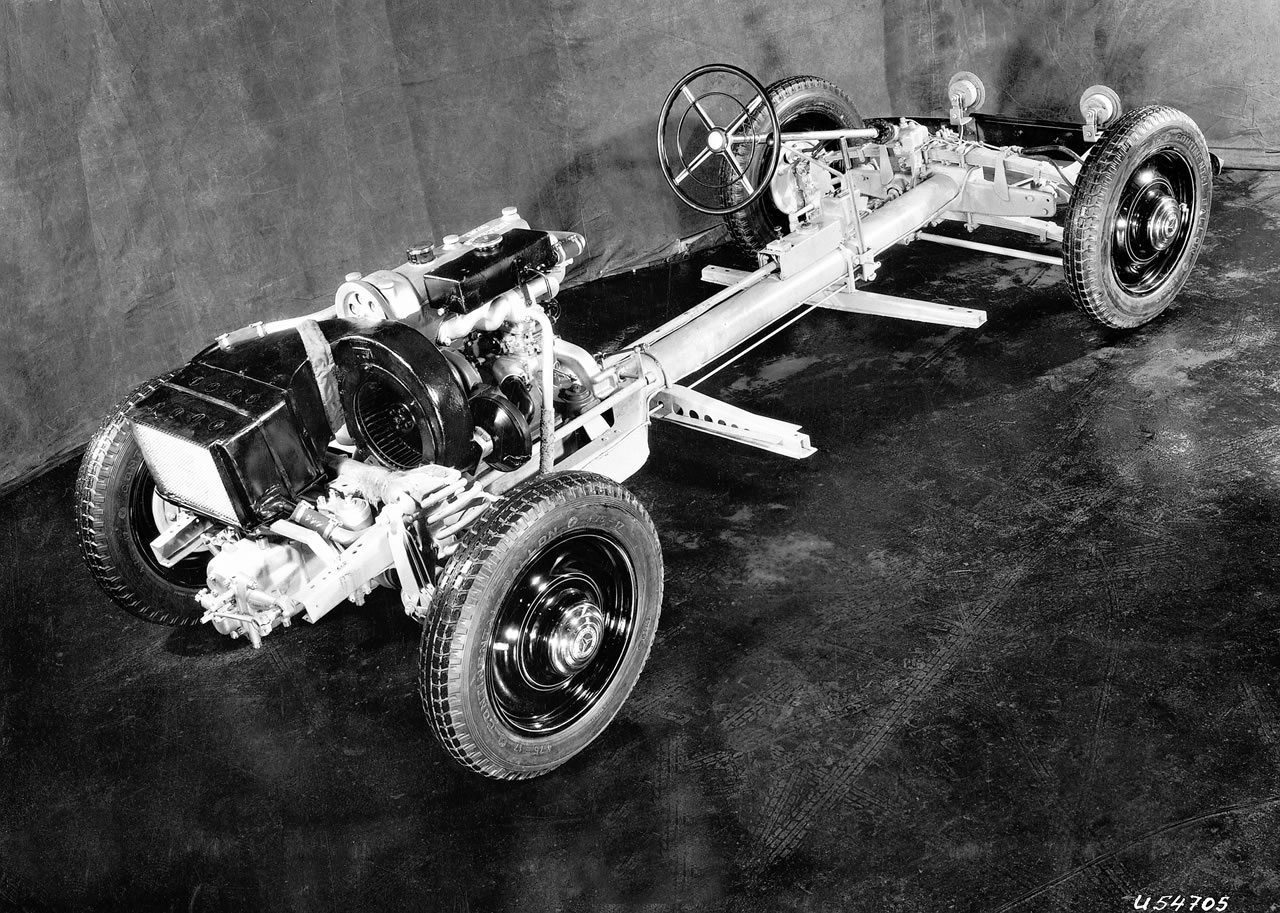

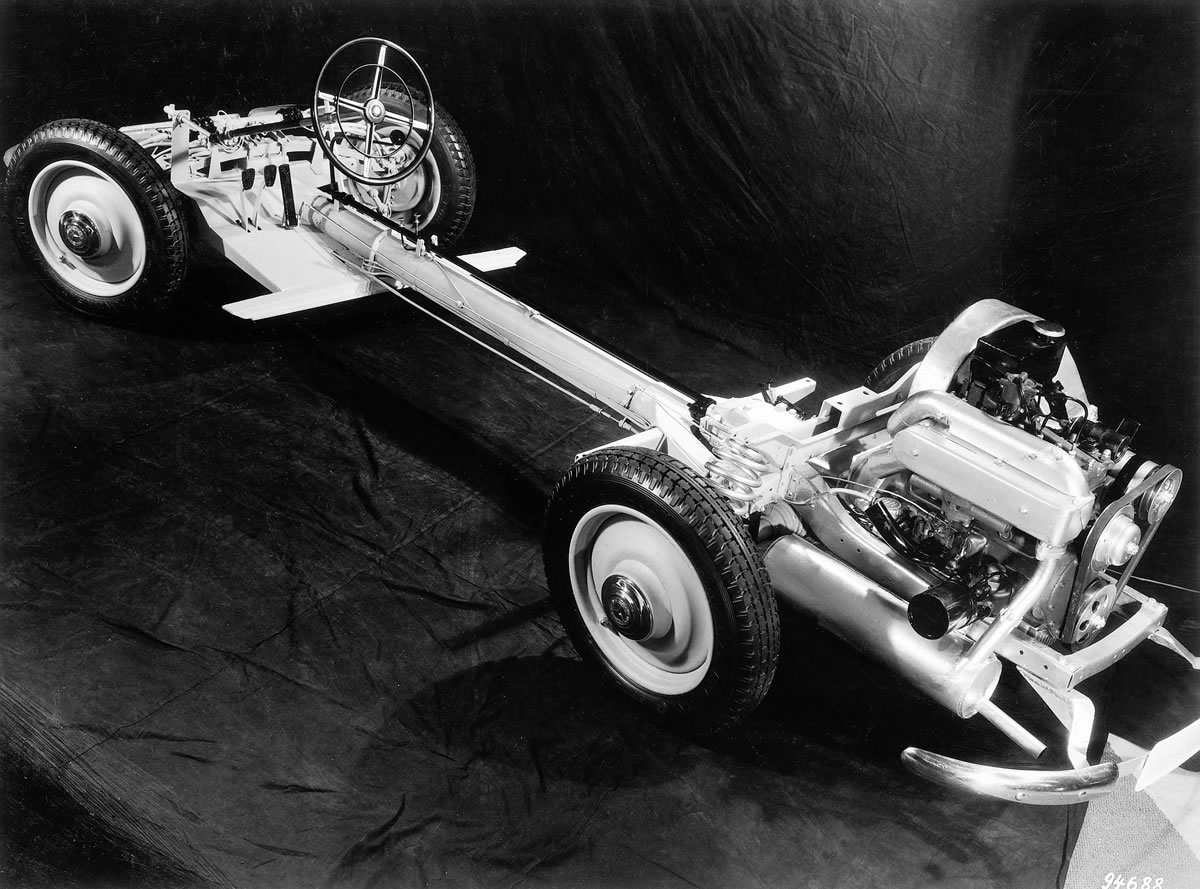

Hans Ledwinka, in his work for Tatra had decided to create a different concept for the chassis of an automobile, it was the germ of an idea that created the first backbone chassis. Ledwinka used a steel tube of sufficient strength and diameter that it could support the body, suspension, engine and transmission of a car all on that one backbone tube. Hans Ledwinka initially created this for an otherwise conventional front engine car driving the rear wheels and he routed the propeller shaft through the backbone tube requiring an independent rear suspension which used swing axles. When Mercedes-Benz chief engineer Hans Nibel set about creating the Mercedes-Benz 130H rear engine saloon in 1931 he chose to use the same type of tubular backbone chassis, bifurcated to accommodate the differential and gearbox. Suspension of the car was independent all around, the front being twin transverse leaf springs, the rear by coil springs with locating arms and leather straps to limit over movement. The suspension thus produced did not locate the rear swing axles with the firmness that would have been preferred, and at the front the double leaf springs similarly did not locate the front wheels with the sort of effectiveness that wishbones or a torsion bar with trailing arms arrangement would have. Thus, although the ride was very comfortable the vehicle handling left much to be desired.

The engine of the 130H was a conventional water cooled in-line 1.3 litre side-valve mounted behind the rear axle line on the differential/gearbox assembly in much the same way the Volkswagen and later Porsche and Abarth cars did. However, this was an iron water cooled engine so it was heavy. The result of hanging that heavy engine at the rear of the car was to create a weight distribution of one third on the front wheels and two thirds on the rear. That combination of suspension that did not locate the wheels as positively as it should, swing axles, and two thirds of the weight concentrated on the rear wheels ensured a car that would over-steer under only modest provocation and that would certainly feel very different and somewhat unbalanced to drivers used to conventional cars.

The car was introduced in 1934 and was available in three body styles, saloon, convertible saloon and cabriolet. Sales were poor and production ended in 1936. Nonetheless the 130H had given Mercedes-Benz the opportunity to test some ideas, learn some valuable lessons, and to come back with something improved.

The Mercedes-Benz 150 Mid-engine Sports Car (W30)

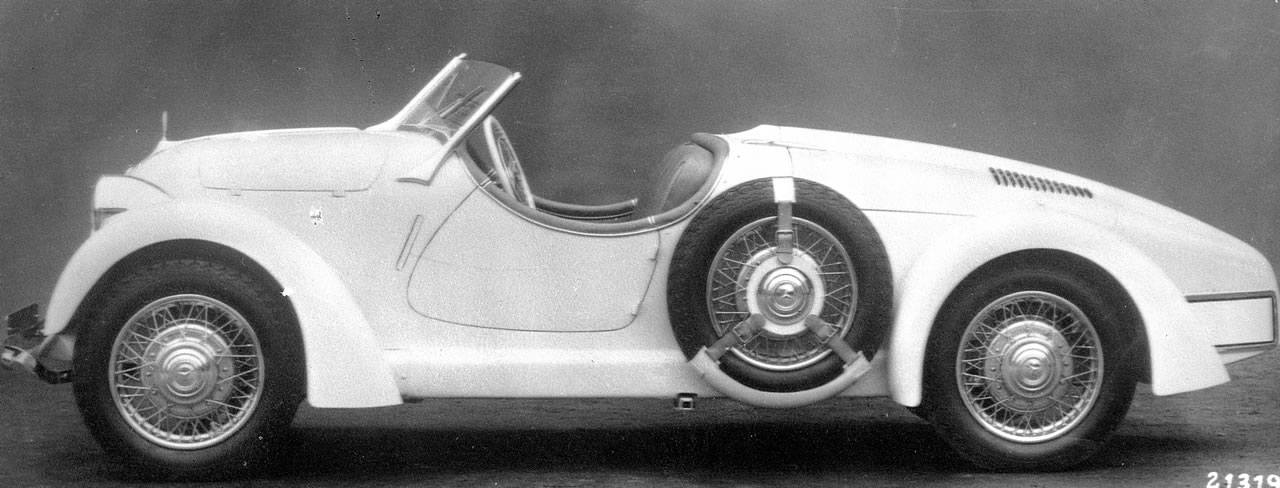

The Mercedes-Benz 150 is the exciting and most desirable of the three rear engined Mercedes. It was designed for sports and competition and so it was a two seater with a mid-engine. Derived from the Mercedes-Benz 130H, with the same basic chassis and suspension design but with a near perfect weight distribution front to rear and powered by a water cooled in-line four cylinder overhead camshaft engine of 1498cc delivering 55hp this was a very different car to the ungainly 130H. Engine cooling was accomplished by squirrel cage blower feeding air to the radiator mounted over the swing axles and to the carburettor. The car was also created by Hans Nibel with input from chassis engineer Max Wagner and introduced in 1934.

The Mercedes-Benz 150 used the available room in the car to place components in such a way as to maximise balance and handling. The fuel tank was located in front of the driver’s compartment, which meant there was no room for luggage there, and the mid-engine ensured there wasn’t room for luggage in the rear of the two seater either. Thus it was a specialist car for competition and sports enthusiasts. Priced at RM6600 it was a thousand RM more expensive than its more conventional rival the Mercedes-Benz 170V. Of the twenty cars that were made in total six were coupés and fourteen roadsters. Production ended in 1936.

The Mercedes-Benz 170H (W28), Almost a “People’s Car”

We all need to make mistakes in order to learn from them. In their creation of their first two rear engined production cars Mercedes-Benz understood they had made some mistakes and were able to identify what they were. Nonetheless they were in a social and political environment that was pushing them to come up with something rear engined, credible, and affordable. Interestingly, although the weaknesses of the Mercedes-Benz 130H were obvious, and the causes of the problems were obvious, it seems there was a determination to continue down the same path in the belief that a successful conclusion could be arrived at. So the next model, the 170H was still based on the same basic flawed design as the 130H. There’s a lesson in this for all of us; sometimes we have an idea we really like and really want to make work, but sometimes it just isn’t going to work and we need to make a list of the things we’ve learned so far, and then start with a nice blank sheet of paper and a freshly sharpened pencil and create something new that addresses the problems that have plagued us. However, if you have someone like Hitler, who had no actual experience of driving, giving you lots of money and at the same time wanting you to create something according to his ideas, fundamentally flawed though they were, you’re stuck, and you know even as you go to put sharp pencil to paper that it isn’t going to be the solution it should be.

So the next car, the Mercedes-Benz 170H was based on the fundamentally flawed design of the Mercedes-Benz 130H.

The Mercedes-Benz 170H was introduced at the International Automobile and Motorcycle Exhibition in Berlin in February 1936 and was available as a saloon or convertible saloon. The engine of the 170H was a conventional water cooled in-line four cylinder of 1697cc producing 37.5hp at 3400rpm. Suspension was almost identical with that of the 130H and weight distribution similar. The 1.7 litre engine capacity was a last minute change and was accomplished by increasing the original 1.6 litre engine’s bore from 72mm to 73.5mm whilst shortening the stroke from 100mm to 98mm. The change was so last minute that some production vehicles left the factory marked as having “1.6Ltr” engines rather than “1.7Ltr”; these are chassis numbers 118771 to 118780 and 136776 to 137775.

Mercedes-Benz chassis engineers spent considerable efforts in tuning the chassis of the 170H to ameliorate the poor handling and succeeded to a significant extent, the car handled notably better than the 130H although it retained the tendency towards over-steer.

Considerable efforts also went in to providing the 170H with excellent build quality and quality trim so it presented as an attractive proposition. Nonetheless, priced at RM4350 the car was quite pricey and was around four times more expensive than Hitler had specified for his “People’s Car”. Build quality, trim quality, and a ride quality that were excellent were in the car’s favour. That it was an unconventional design with somewhat quirky handling and had an appearance that made it look remarkably similar to the much cheaper and consequently lower status Volkswagen, or (KdF Wagen as it was known at that time) did not work in its favour.

The outbreak of the Second World War in 1939 brought production of the Mercedes-Benz 170H to an end.

These pre-war Mercedes-Benz are interesting cars that reflect the troubled history of Germany during the decade between the Great Depression and the Second World War. They were products created under an unusual political and social regime and bear the stamp of that socio-political climate in addition to bearing the stamp of some of the greatest automotive engineers of the twentieth century.

For the collector these cars can form the basis of a historically significant automotive collection especially if combined with some of their peers, such as the original Volkswagen created by Dr. Ferdinand Porsche, and the Steyr 50 and 55 “Baby”. They are cars that can be obtained at reasonable prices and they are cars that were designed to be repaired and re-furbished, so they can typically be restored without excessive problems or costs.

They are also cars that are affordable enough to be driven and enjoyed, and isn’t that a large measure of the enjoyment of collecting?

Jon Branch is the founder and senior editor of Revivaler and has written a significant number of articles for various publications including official Buying Guides for eBay, classic car articles for Hagerty, magazine articles for both the Australian Shooters Journal and the Australian Shooter, and he’s a long time contributor to Silodrome.

Jon has done radio, television, magazine and newspaper interviews on various issues, and has traveled extensively, having lived in Britain, Australia, China and Hong Kong. His travels have taken him to Indonesia, Israel, Italy, Japan and a number of other countries. He has studied the Japanese sword arts and has a long history of involvement in the shooting sports, which has included authoring submissions to government on various firearms related issues and assisting in the design and establishment of shooting ranges.