Are there machines that are more exciting to drive than a Bugatti Veyron or a McLaren P1? I suspect there are, or at least that there used to be. Back when I was a boy most boys wanted to grow up to become a train driver. In our little boy minds we knew that the job driving the big, loud, smelly and wonderfully dirty steam locomotives was pretty much the best job a boy could want. Iron, earth, fire, water and speed, what more could there be in life? Sadly few of us ever achieved that dream, partly because the railroads only need a small number of drivers, and partly because the steam locomotives that look so exciting to drive were being phased out and replaced with diesels that just didn’t have any of the personality of the steam locomotives.

It was in the United States that the steam locomotives were developed into the fire breathing behemoths that inspire awe just being near them. Park one of the big American locomotives of the forties next to something from Britain and the sheer size differential becomes obvious. Just as Americans were building the biggest cars with the biggest V8 engines so they were also building the biggest steam locomotives and driving them at high speed. Speeds on American mainlines such as the New York Central and the Pennsylvania were commonly over a hundred miles per hour and the passenger locomotives themselves grew to total weights around four hundred tons. The New York Central’s Niagara’s for example tipped the scales at 405 Long Tons.

The New York Central Railroad’s main competitor was the Pennsylvania Railroad and between the two there emerged a bit of an arms race to see who could create the most interesting locomotives and the quickest, whilst being fuel efficient. Whilst the New York Central’s Hudson and Niagara locomotives were conventional the Pennsylvania Railroad was willing to experiment and so they came up with some of the most creative locomotive designs ever seen. These included their Raymond Loewy styled S1 duplex and the “shark nose” T1 duplex.

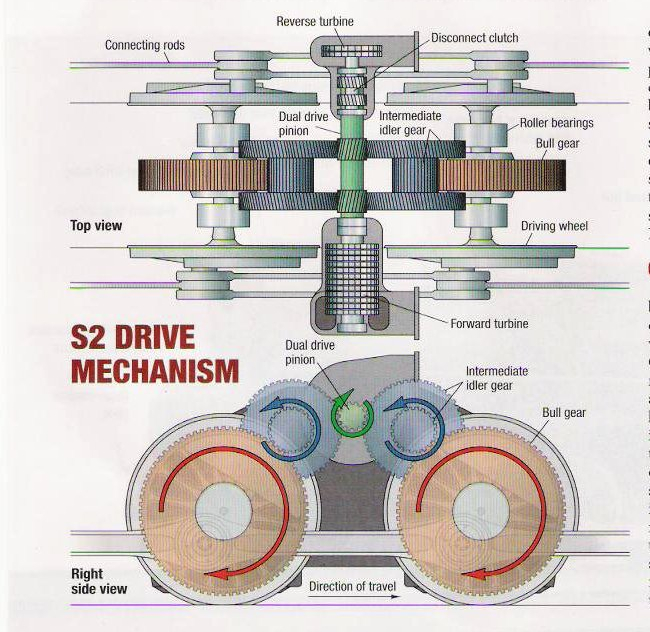

Beginning in 1937 Baldwin-Westinghouse engineers got working on applying steam turbine technology to steam locomotives. With the Second World War creating materials shortages there were some design decisions that had to be made that would have been done differently in peace time. But the Pennsylvania Railroad and Baldwin-Westinghouse set out to create the most efficient steam locomotive ever made. Navy ships were not powered by reciprocating steam engines but by steam turbines which made them quicker than anything else on the water because of the inherent efficiency and power of the turbine. So by the same logic building a steam turbine railroad locomotive made a lot of sense. The decision was taken to make the locomotive use a direct drive steam turbine which meant there would be no need for a generator or traction motors as are found on diesel locomotives but which also required the fitting of two turbines, one for forward travel and another smaller one for reverse travel.

As diesel locomotives were rapidly gaining popularity and were providing significant gains which pleased the financial managers at the railroad companies we must wonder why anybody would bother with trying to come up with a new style of steam locomotive. Although there were practical reasons I tend to think that there were people in senior management at some railroad companies that just loved steam locomotives and wanted to keep using them. Perhaps as boys they’d wanted to be steam locomotive drivers but finished up going to college and becoming managers and executives instead. From a practical standpoint steam locomotives used coal as fuel and this was half the cost of diesel fuel. The Pennsylvania Railroad did a lot of business hauling coal for industry and they were keen to keep right on doing that. They could see the potential for economy and a good bottom line result that would still allow them to use steam power. The fact that the navy’s warships were successfully using steam turbines and Baldwin-Westinghouse were builders of those turbines augured well for a steam turbine railroad locomotive with a direct drive system as ships also used direct drive systems and thus gained efficiency because an electric transmission inevitably causes a loss of efficiency due to the generation and then transmission of the electrical energy.

With wisdom with the benefit of hindsight the Pennsylvania Railroad probably should have chosen to build a low speed freight locomotive as their first prototype. The chances of success would have been better. However the decision was made to create a high speed passenger locomotive – it’s the romantic decision that every boy would make. So the S2 was conceived as a high speed passenger locomotive that would be absolutely fantastic to see in action and probably the most exciting man made machine to drive ever created.

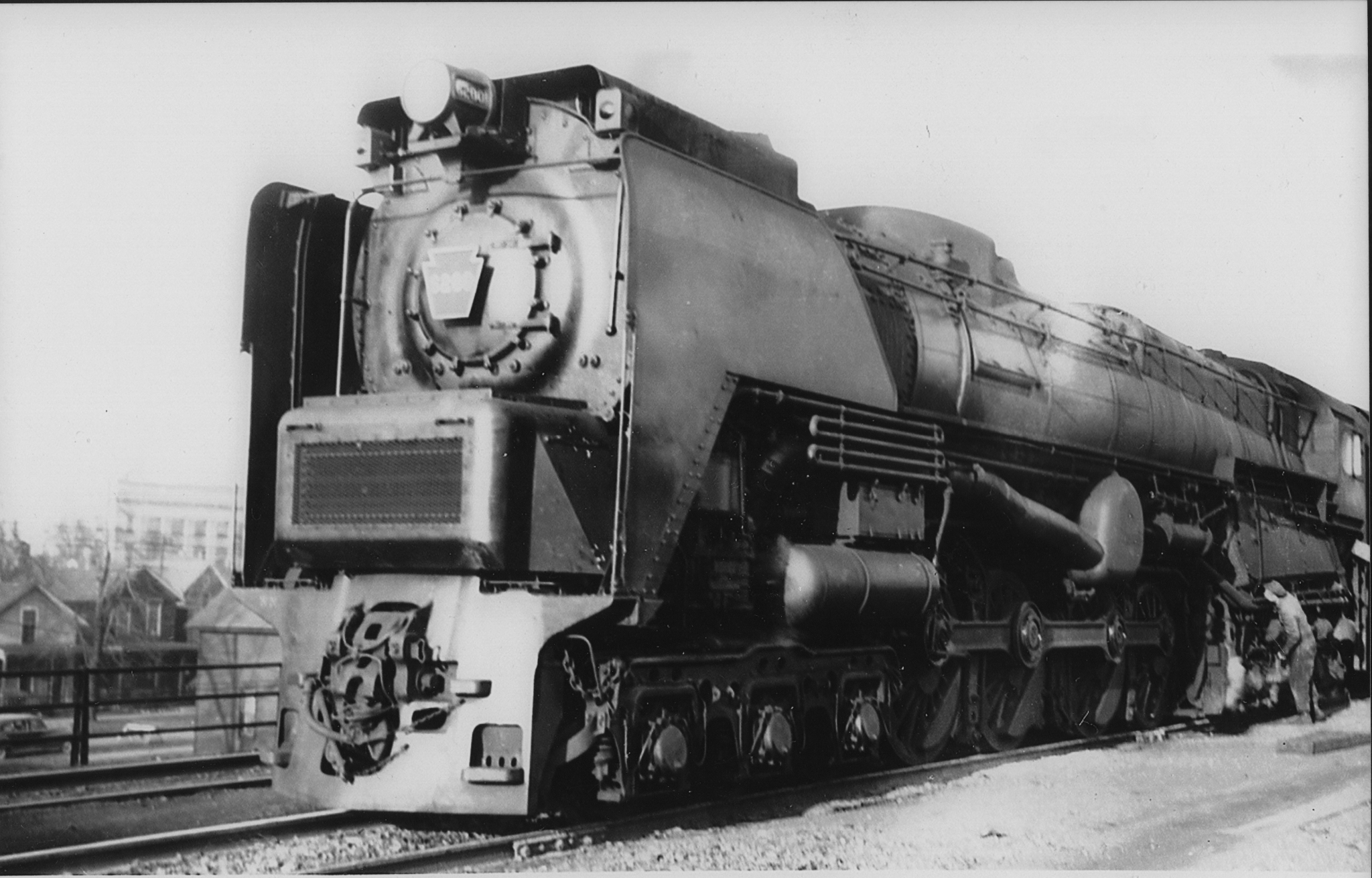

The S2 steam turbine locomotive made its grand debut in 1944. It was a steam locomotive with a difference. Instead of the familiar “chuff chuff” of the reciprocating steam engines it made a powerful “whoosh” which was new and space age sounding. At the head of a high speed inter-city train this was a locomotive that was easily capable pulling a full load at over a hundred miles per hour and once it got over forty miles per hour it would do it more efficiently than the triple unit Electro Motive E7 diesel that would be needed to match its power. At speeds below thirty to forty miles per hour however it was coal hungry and water thirsty. A steam turbine needs to be spinning at a set speed in order to be efficient and the design decision had been made for the S2 that the peak efficient speed would be 70mph.

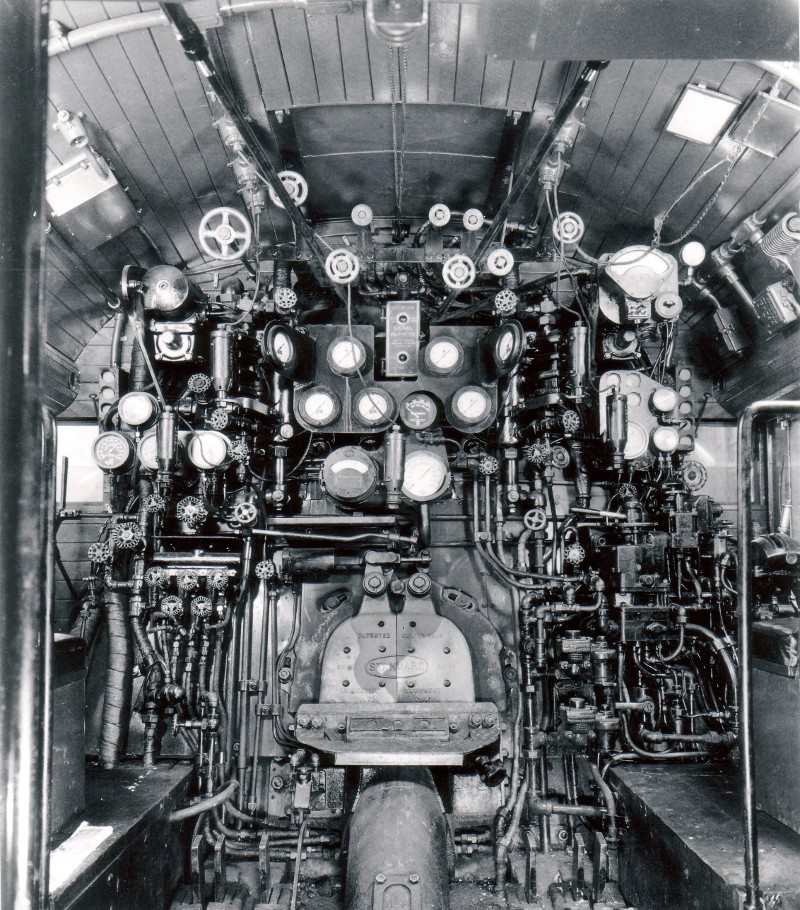

It was in starting a train that the steam turbine encountered most trouble. Overcoming the initial resistance of a typical twenty car train and getting it moving would cause the boiler pressure of the S2 to drop from over 300psi to around 100psi. This sudden drop created thermal problems in the firebox and failure of staybolts which meant the S2 spent rather a lot of time in the workshops instead of pulling trains. Much effort went into trouble shooting the problem and it was discovered that the design was faulty and that a new design for boiler and firebox would be needed. It was the final nail in the coffin for the S2 and after only six years on the tracks it was retired in 1949. Could the problems have been resolved? Almost certainly, Baldwin-Westinghouse were a technologically advanced company as is evident in the control systems created for the S2. Without the use of computer technology using only mechanical means the complex issues of controlling the two turbines, one for forward motion and a smaller one for reversing, and controlling the selective opening of the four smoke stacks one at a time as speed and load increased were controlled by a management system. This was necessary as the driver (engineer) would simply not have time to manage those precise and complex tasks. So the S2 remained quite conventional to drive. So the teething problems of this new design could have been sorted out and it would have been wonderful for the people who had the opportunity to drive it, and a real blast for those riding behind it or seeing it out on the tracks.

As it turned out though steam motive power was doomed as the diesel locomotives were not just cheaper to run but they required less staff to service and maintain them. No fireman was needed so the train driver’s life became a solitary one, so solitary and boring that the diesel locomotives had to be fitted with a “dead man’s pedal” that the driver had to regularly press to check he hadn’t gone to sleep.

There was something about the ending of the steam locomotive age that didn’t seem to do the railroads any good. People progressively stopped using trains for travel and started traveling by car or bus. The result was that the railroad companies had to amalgamate to try to survive, the Pennsylvania Railroad merged with its arch rival the New York Central to become Penn Central, and then in 1970 they went bankrupt in the biggest corporate bankruptcy of American history up to that time. Why? Economics is one issue, but I think the issue that no-one seems to consider is that the railroads had lost their romance with the passing of the steam age. They chose the cheapest option rather than the imaginative option. The Pennsylvania Railroad’s S2 steam turbine locomotive was an imaginative attempt at keeping the romance of the railroads alive, an attempt at ensuring that all school boys would continue to want to be a locomotive engineer when they grew up. Sadly it didn’t succeed, although it could have.

That the Pennsylvania Railroad’s S2 was a style icon is evidenced by toy and model train maker Lionel creating a train set based on the Pennsylvania Railroad’s S2 steam turbine. The set was wildly popular. The little boys who wanted a Lionel Pennsylvania S2 train set knew that this was a locomotive they really wanted to play with.

You will find the high resolution copy of the above picture of the boy and the S2 locomotive on Flickr if you click here.

You’ll find three other high resolution photos of the Pennsylvania S2 on Flickr if you click here.

They make great desktop wallpapers.

You will find a much more detailed technical article on the Pennsylvania Railroad S2 from the Classic Trains magazine issue of Spring 2012 on omnibus.bobanna.com if you click here.

Jon Branch is the founder and senior editor of Revivaler and has written a significant number of articles for various publications including official Buying Guides for eBay, classic car articles for Hagerty, magazine articles for both the Australian Shooters Journal and the Australian Shooter, and he’s a long time contributor to Silodrome.

Jon has done radio, television, magazine and newspaper interviews on various issues, and has traveled extensively, having lived in Britain, Australia, China and Hong Kong. His travels have taken him to Indonesia, Israel, Italy, Japan and a number of other countries. He has studied the Japanese sword arts and has a long history of involvement in the shooting sports, which has included authoring submissions to government on various firearms related issues and assisting in the design and establishment of shooting ranges.