While many people are aware of Bugatti’s automobiles there are few who are familiar with the one attempt Bugatti made at creating an aircraft, and not just an aircraft for transport, but an aircraft for racing.

Fast Facts

- Ettore and Jean Bugatti seem to have been determined to establish themselves not only as makers of fine automobiles, but also to branch out into railway vehicle and aircraft design and construction.

- They were successful in branching out into railway railcar making and delivered 88 of their high speed railcars to the French railways.

- The move into aircraft design and construction required the recruitment of someone with established expertise in this field, they managed to recruit Louis de Monge, who was both skilled and experienced.

- Just as Bugatti had established their name as a car maker by auto racing so they decided to make a name for Bugatti by winning a major air race – the Deutsch de la Meurthe Cup Race which was to be held in 1939: events prevented this from happening.

- In the early years of the 21st century an ex USAF pilot named Scotty Wilson decided to build a new Bugatti 100P and fly it, to bring to fruition the vision of Ettore and Jean Bugatti, and of Louis de Monge.

The Bugatti 100P History

In my experience, men tend to be fascinated by “planes, trains, and automobiles”, and the Bugatti father and son team of Ettore and Jean were no exception. They started out making some of the most beautiful and most beautifully engineered automobiles the world had seen up into the 1930’s: and they also branched out both into trains, and into aircraft.

Interestingly the efforts to establish the Bugatti name in the fields of railway transportation and aviation both occurred in the late 1930’s, at a time when the world had left the privations of the Great Depression behind and Jean Bugatti had become a mature member of the Bugatti leadership.

Ettore Bugatti had made his mark on the automobile industry initially by racing and winning. His characteristically styled French blue racing cars became something of an auto racing icon and as Bugatti began fitting the straight eight engines of his own design and manufacture not only in racing cars but in the road cars he sold his automobiles became even more highly desired by the fashionable and monied clientele who purchased them.

This cachet transferred to his high speed railcars also: it sounds much more exciting to say “Let’s take the Bugatti to Lyon” referring to the luxurious high speed Bugatti railcar service to Lyon, rather than saying “Lets take the train to Lyon”.

Even as Ettore and Jean were working on the creation of their range of railcars so they also turned their attention to the idea of becoming involved in aviation. They realized that the best way to do this would be to create a Bugatti racing aircraft that could win the Deutsch de la Meurthe Cup Race: these were not run every year, but there was to be a race held in 1939.

Neither Ettore nor Jean had expertise in the design of aircraft but in 1937 managed to recruit an aviation designer with the rather long name of Vicomte Pierre Louis de Monge de Franeau, which is generally abbreviated to Louis de Monge.

Louis de Monge had been a flight enthusiast since his boyhood creating model gliders which he flew by launching them from the ramparts of his family’s castle. By 1921 he had built a racing aircraft to compete in the 1921 Deutsch de la Meurthe Cup Race. This aircraft was unusual in that it was actually a high wing monoplane with a removable lower wing – making it a monoplane/biplane convertible. This aircraft managed a speed of 198 mph when flown as a biplane, which at that time was a world record.

Sadly when de Monge tried removing the lower wing in an attempt to improve the plane’s speed and handling it ran into flutter at high speed sufficiently severe that the test pilot lost control and was killed in the ensuing crash.

The 1920’s were very much the experimental phase of powered flight and crashes of this kind were the by-product of the quest for technical knowledge. The people involved in this experimental phase knew the risks, and were willing to take them.

De Monge was a highly creative designer and he obtained a number of patents for unusual technology including flying wings and automated flight control systems.

Perhaps it was his creative and experimental background that led to Ettore and Jean Bugatti deciding that he was the right man to design a new Bugatti racing aircraft: de Monge was an “out of the box thinker” just as Ettore and Jean were.

The design brief given to de Monge was to create a single seat racing aircraft with which to win the Deutsch de la Meurthe Cup Race, and then to design a single seat military aircraft approximately based on the racing plane with the potential to sell those aircraft to the French Government. This is like the process by which the British company Supermarine created the iconic Spitfire. It began as a racing aircraft, and that design formed the ideas foundation for the creation of the fighter that was to play such a significant role in the Battle of Britain.

Ettore and Jean Bugatti wanted to use Bugatti straight eight engines to power this new aircraft. During the First World War Ettore Bugatti had done a design for a 16 cylinder “U-16” aircraft engine of 31.4 litres capacity made by literally joining two 15.7 litre straight eights side-by-side. That engine produced 450 hp and so impressed the United States Bolling Commission that they paid Bugatti US$100,000 for it with a view to using it in military applications.

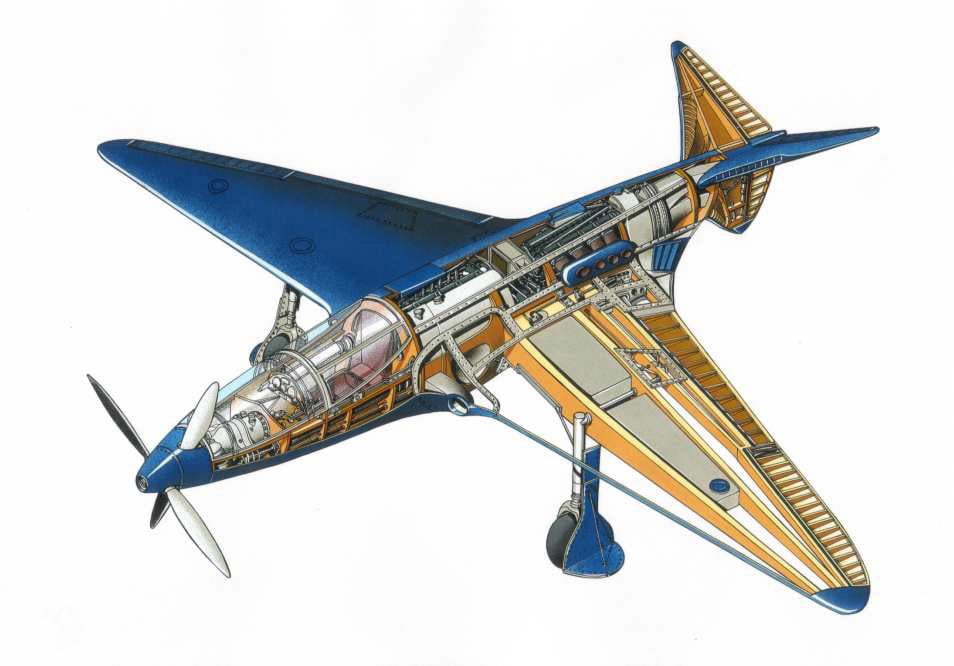

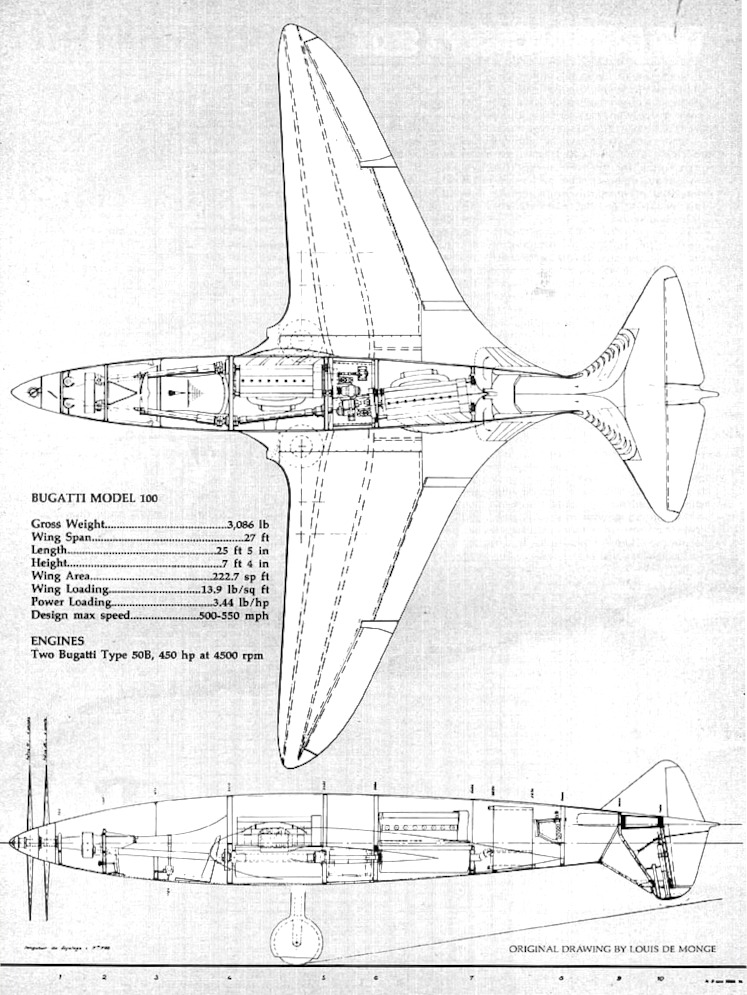

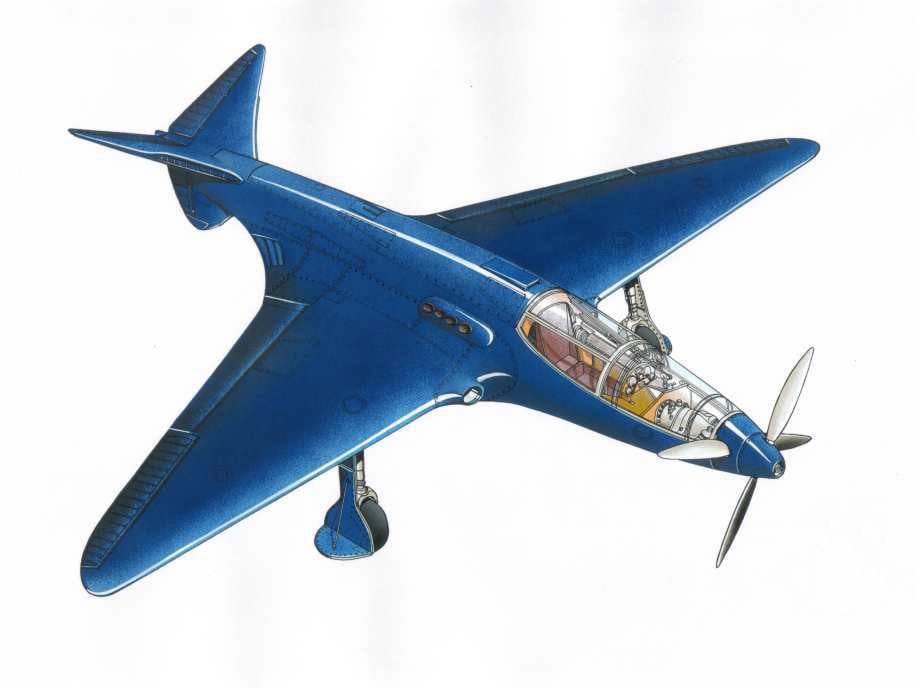

But the U-16 was not to be the engine for the new Bugatti 100P racing plane. Instead Bugatti and de Monge decided to use two separate straight eight Type 50B racing engines, one mounted in the slender fuselage behind the other, and the drive to the contra-rotating front mounted propellers being routed through a specially designed gearbox.

These engines used for the 100P were those used in the Bugatti Type 59 racing car. The engine was the 50B of 3.3 litres (3,257 cc/198 cu.in) capacity. These were supercharged DOHC straight eights with 16 valves and produced approximately 450-500 hp each at 4,500 rpm.

Bugatti obtained the second floor of a furniture factory in which to construct the new 100P racing aircraft. For the construction of the bodywork of the aircraft itself de Monge used a laminated composite of balsa and hardwood for the frame, with tulip wood stringers and a conventional covering of dope treated fabric. He also specified the use of magnesium where possible. Magnesium is a very light metal but suffers from being quite flammable, and it burns with a very hot flame.

De Monge’s design for the wings and the tail both had unusual features, the wings are angled slightly forward while the tail assembly featured a vertical stabilizer that sat vertically down, and provided the mounting for the tail wheel, with the horizontal stabilizers mounted at an upward sloping angle.

Work on the 100P got underway with the aim to have the aircraft ready in time to compete in the 1939 Deutsch de la Meurthe Cup Race, the chance Bugatti wanted to establish the company as a credible aircraft maker. But events threw up roadblocks to the completion of the aircraft. Ettore’s much loved son Jean was killed testing a Bugatti racing car on 11th August 1939, and hard on the heels of that tragedy the Nazis invaded Poland on 1st September plunging Europe into the Second World War.

We can only imagine the grief Ettore Bugatti, his wife Barbara, and their surviving children endured.

The Battle of France began on 10th May 1940 and as the German Blitzkrieg progressed it was clear that the Bugatti 100P aircraft needed to be made to disappear: it was much too much like a fighter aircraft and the Germans would be quite delighted to get their hands on the technology incorporated into it, and to get their hands on the people responsible for its design and construction.

So the Bugatti 100P was whisked away to a farm barn in the French countryside where it stayed out of sight, out of mind, and safe: and by remaining secret it also kept its creators safe until the war’s end.

Ettore Bugatti passed away in 1947 at the age of 66 years. He saw the Nazis defeated and his beloved France set free from them. But the war and the personal tragedy had taken its toll on him.

The Bugatti 100P sat mostly forgotten in the barn until it was sold to a Mr. Pazzoli, who then sold it on to a Mr. Salis, who was approached in 1970 by American car enthusiast Ray Jones, who was interested in acquiring the two Bugatti Type 50B supercharged engines fitted into the aircraft although he wasn’t interested in the 100P itself.

Ray Jones was able to sell the 100P aircraft, without its engines, to Dr. Peter Williamson who moved it to Connecticut and undertook the plane’s restoration for static display. He had Les and Don Lefferts work on the restoration from 1975 until 1979 and then Dr. Williamson donated it to the Air Force Museum Foundation hoping that the restoration would be able to be completed and that the 100P would finally find a resting place in a museum where it could be appreciated by many.

After languishing in storage for another fifteen years the 100P was finally passed on to the Experimental Aircraft Association in 1996, and they undertook the completion of the restoration.

The 100P is now on display in the EAA’s AirVenture Museum in Oshkosh, Wisconsin, to be appreciated by those who come to admire that penultimate example of the Bugatti creativity in blending engineering with art.

The story of the Bugatti 100P might have ended there, but it didn’t. This was a Bugatti creation with enormous potential to grab the imagination: a Bugatti with wings powered by two Bugatti supercharged straight eights – there’s a lot of fascinating potential in that.

Le Rêve Bleu—The Blue Dream

The potential of the 100P design and heritage was not lost on ex USAF fighter pilot Scotty Wilson, who decided that the 100P was to be an aircraft he was going to build and fly: he was an example of the combination of determination and conscientiousness that are precursors to success. Both Ettore and Jean Bugatti also epitomized those same attributes.

A team of committed enthusiasts came together which included Louis de Monge’s great-nephew in America, and a Kickstarter project was established to help finance the project.

A workspace was obtained and equipped and work began to bring a new 100P into being.

Some changes were required in the design and construction, for example, it would not be possible to find two original Bugatti Type 50B straight eight supercharged racing engines, and even if they were able to be found they would be hopelessly expensive.

For engines twin Hayabusa motorcycle engines were chosen. Instead of the type of laminated wood construction used by de Monge a modern wood composite called DuraKore was used and glued with modern epoxy. Instead of doped fabric fibreglass was substituted, and magnesium was not used because of its fire risk, Aluminum alloys were a much safer alternative.

The aircraft was completed and the first taxi test was done on the 4th July 2015, with progressively faster taxi tests before the first tentative flight just off the runway.

(Video courtesy Bugatti 100P project.)

After two successful test flights Scotty Wilson embarked on the third, and final, test flight. After the third flight he intended to retire the aircraft so it would go on display in the EAA’s AirVenture Museum.

This was to prove to be a tragic test. As the 100P was taking off it suffered an increasingly severe power loss of the front engine. Later investigation discovered that this was most likely caused by the clutch of that engine slipping, and that slippage getting progressively worse.

The result was the aircraft becoming uncontrollably unstable, and losing speed as it did so. Despite Scotty Wilson’s years of training and experience he was not able to regain control and the 100P crashed killing him, and bursting into flames.

It was a tragic end to a visionary project.

Scotty Wilson was 66 years old when he died: which seems a coincidence as Ettore Bugatti was also 66 when he passed away.

Thus the story of the Bugatti 100P and the people who created it, and those who tried to re-create it, came to an end. The end in each case was tragic: but I think it is far better to give your all to achieve your vision, rather than deciding that its all too hard, and allowing yourself to be content with the mundane.

Picture Credits: Feature image at the head of this post by Phil West.

Jon Branch is the founder and senior editor of Revivaler and has written a significant number of articles for various publications including official Buying Guides for eBay, classic car articles for Hagerty, magazine articles for both the Australian Shooters Journal and the Australian Shooter, and he’s a long time contributor to Silodrome.

Jon has done radio, television, magazine and newspaper interviews on various issues, and has traveled extensively, having lived in Britain, Australia, China and Hong Kong. His travels have taken him to Indonesia, Israel, Italy, Japan and a number of other countries. He has studied the Japanese sword arts and has a long history of involvement in the shooting sports, which has included authoring submissions to government on various firearms related issues and assisting in the design and establishment of shooting ranges.