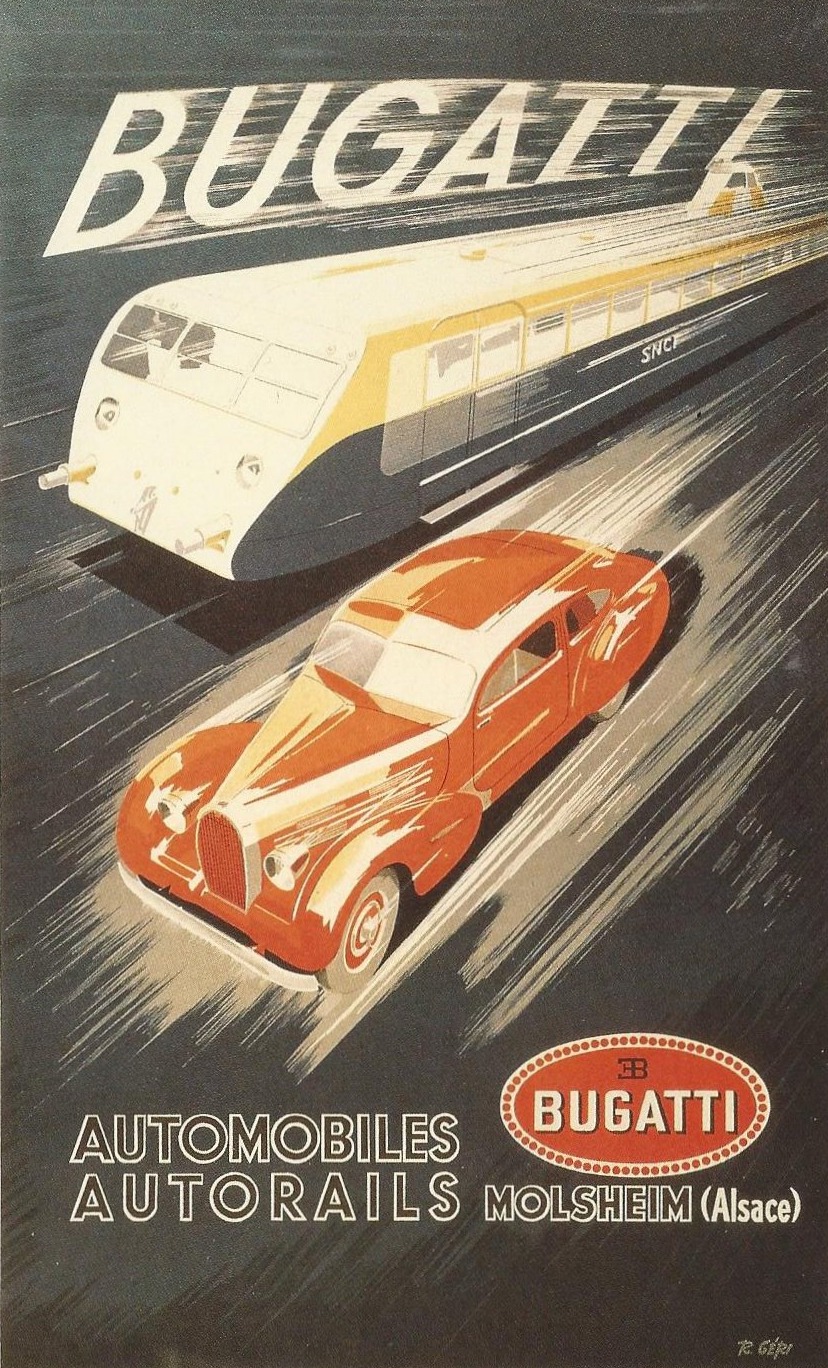

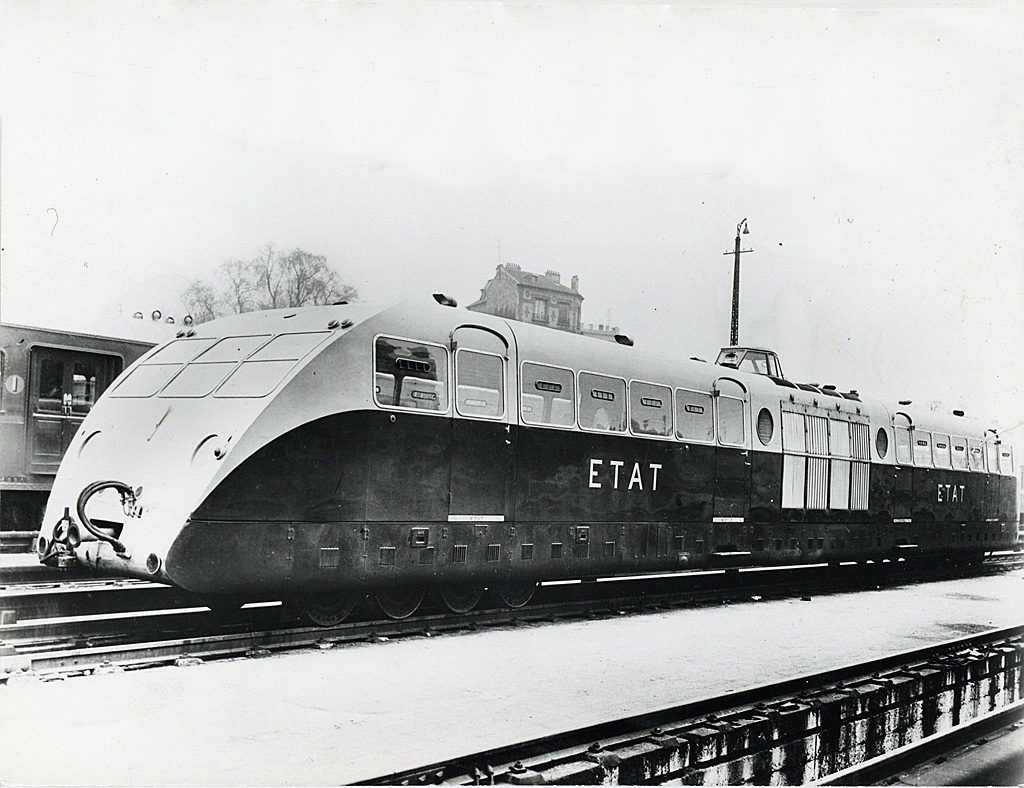

It looked a bit like a Bugatti Type 32 “Tank” racing car that had been crossbred with a train: That being said it was far more powerful than the Type 32 Tank, it was a lot bigger, and it gave a nice comfortable high speed ride to a great many more people.

Ettore and Jean Bugatti blended the idea of a Bugatti racing car and a train and came up with a creation guaranteed to be described as “c’est manifique“.

Fast Facts

- Although many people have heard of Bugatti motor cars there are few who are familiar with the Bugatti “Pursang” (i.e. “thoroughbred”) high speed railcars which graced the French railways from the 1930’s up until the last was retired from service in around 1956-1958.

- There were two main models of the Bugatti railcar made, a lighter and less expensive two engine model and a four engine model which came in single unit, twin unit, and triple unit forms.

- These railcars were made from 1933-1939 and were powered by the same basic 12.7 litre straight eight engine as used in the Bugatti Royale automobile, but modified for railcar use.

- 88 of these Bugatti railcars were made and sold to French railways, of these only one survives to the present day.

It is said that “without a vision the people perish”, and so we should reasonably expect that when people have a vision they are likely to prosper. Such was the case for the father and son team of Ettore and Jean Bugatti.

Although famous for their astonishing automobiles, the Bugatti’s vision extended beyond that and ventured into the realms of aircraft design, and high speed railcars for the French railway network.

Ettore and Jean Bugatti were a father and son team with great imagination, and they had the ability to actually build the things they imagined. They had designed an aircraft, and a car with which to make an attempt at the land speed record, and in addition to this was the plan to create a train that incorporated all the essence that was Bugatti, a train that would become a high speed fashion icon.

Why would Ettore and Jean want to build a railway train? I think there were a couple of reasons, firstly the 1929 Great Depression had sent a number of the most famous makers of luxury cars into bankruptcy, and Ettore and Jean understood the need to transform their company or potentially see it perish. Secondly, mass transportation looked set to become a booming market with a great future.

There were, of course other makers who were making railcars, but these were usually made to provide inexpensive rail transportation for use on branch lines to smaller population centres which were not economical to service with full-size conventional trains. Such railcars presented no exotic mystique, just no frills mundane transportation.

Ettore and Jean understood that they would need to compete in that lower cost end of the market, but they decided to also offer luxury high-speed rail main-line travel, in a sense pioneering the luxurious high speed trains that we now enjoy, and offering a rail vehicle that would be less expensive to build and run than the full-size steam locomotives of the era and their rolling stock.

The steam locomotives of France in the 1930’s were some of the most advanced in the world: locomotive engineer Andre Chapelon being perhaps the most famous for his designs which were at once amazingly efficient, fast, and things of graceful beauty.

In order to compete Bugatti needed to operate in a completely different sector of the market and offer something that provided a Bugatti style vehicle complete with high performance engines of awe-inspiring power, and a quiet, comfortable and stylish high speed ride achieved through the use of a custom designed suspension. They even used a custom fuel mix which gave their engines both power and the fragrance of racing fuel to quicken the pulse of car enthusiasts.

The Bugatti Railcar Models

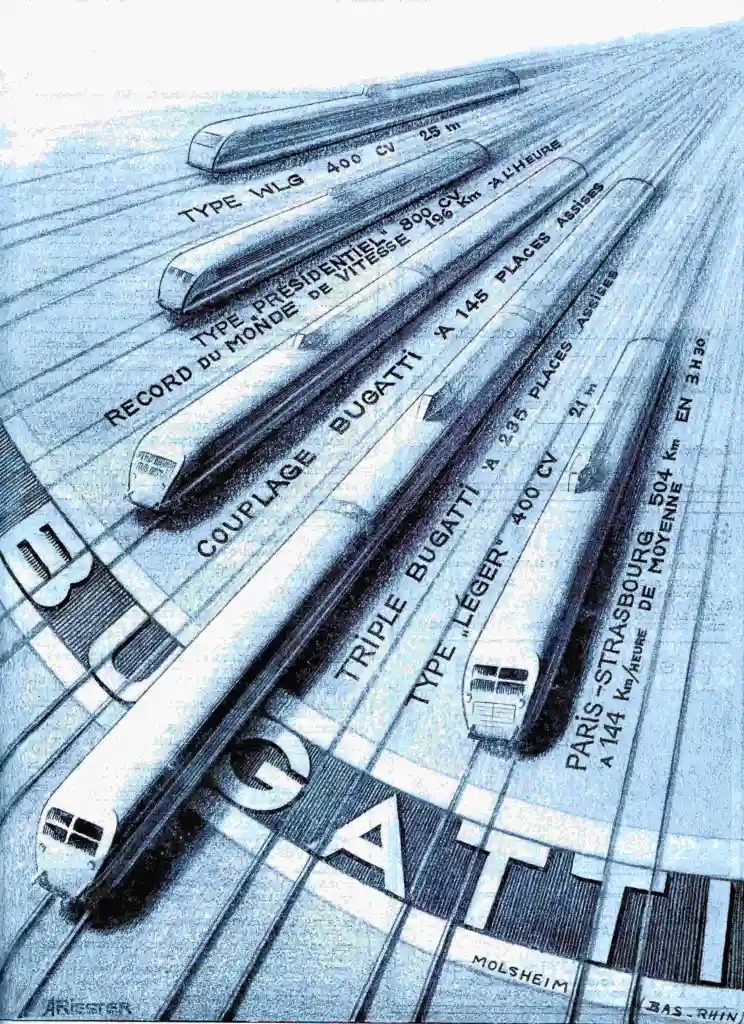

Bugatti’s “Automotrice” (railcars) were made in two basic versions; a light and economical WLG model designated the “Wagon Léger” (i.e. “light wagon”), and a WR “Wagon Rapide” high speed model.

From these two main model groups Bugatti made a number of variants to suit the different rail administration customers he was selling to.

The WLG Wagon Léger

The WLG version was designed to be light and inexpensive. It was fitted with two of the straight eight 12.7 litre 200 hp engines as used in the large and luxurious Bugatti Royale automobiles but specifically modified for railway use. With two straight eights the WLG had 400 hp with which to power the railcar.

One model of the WLG was 25 metres long and typically ran as a single unit. A custom WLG created for the Paris to Strasbourg route was shortened to 21 metres long. This Automatrice covered the 504 km in 3 hours and thirty minutes with an average speed of 144 km/hr.

That average speed indicates that the Bugatti railcar was at times doing rather more than 144 km/hr to attain that average and such speeds were, and are, quite impressive. That being said we should remember that around the world during the 1930’s steam locomotives were in some places, including Britain and the United States, delivering 100 mph speeds in regular service.

In France steam locomotives on the SNCF national rail network were limited to a 120 km/hr (75 mph) speed limit, a regulation that gave the Bugatti railcars an advantage as they were not subject to it.

The WR Wagon Rapide

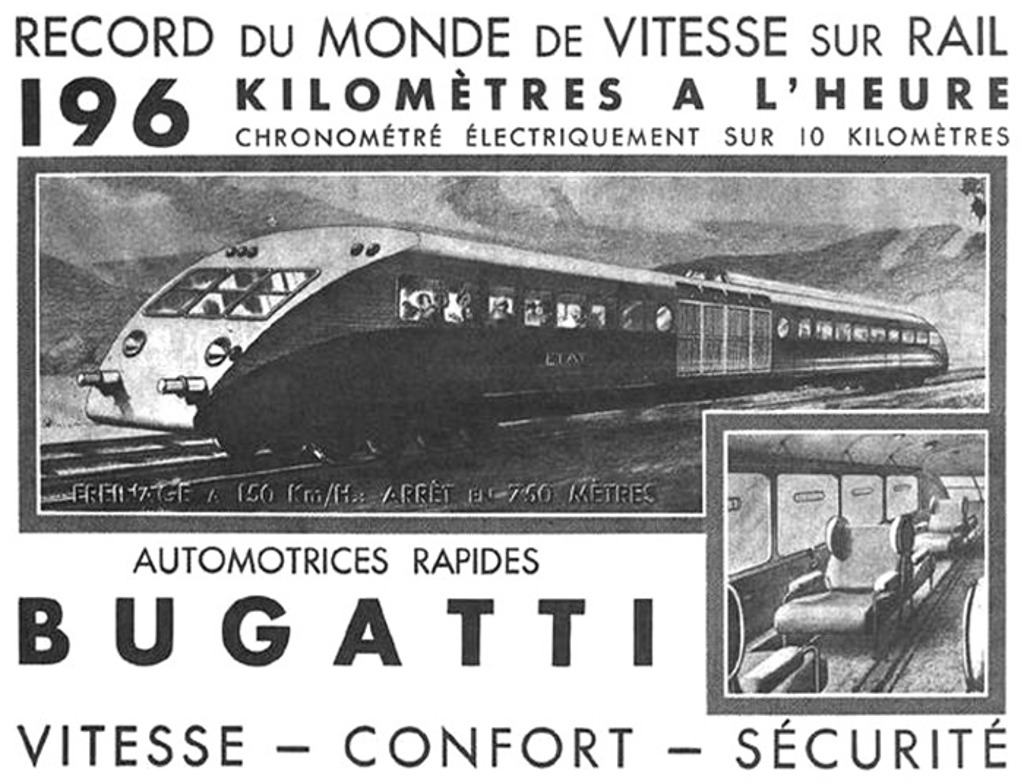

The Wagon Rapide top model was the “Presidentiel”, which was made as a 1st class high speed machine to appeal to the affluent of French society. This was the model that was used to set a world speed record of 196 km/hr.

The WR were fitted with four of the 12.7 litre 200 hp straight eight engines as first used in the Bugatti Royale luxury automobiles. Running on ordinary gasoline/petrol these engines produced 200 hp. But Bugatti also made their engines for these railcars to run on more potent fuel mixes to boost power. There were two special fuel versions; a gasoline/benzole mix with a small touch of alcohol that gave the engine an output of 215 hp, or a mix of 55% gasoline, 30% Benzene, and 15% alcohol which pushed power up to 225 hp. These power figures being delivered at 2,500 rpm.

The fuel tank for each engine was fitted underneath it.

The four engine version of the Bugatti railcar was also offered as a two car or a three car set. As one would expect these multiple car sets were much heavier than the single car units. The triple car unit on the Paris to Strasbourg and return route delivered a 114 km/hr commercial service.

Design and Construction

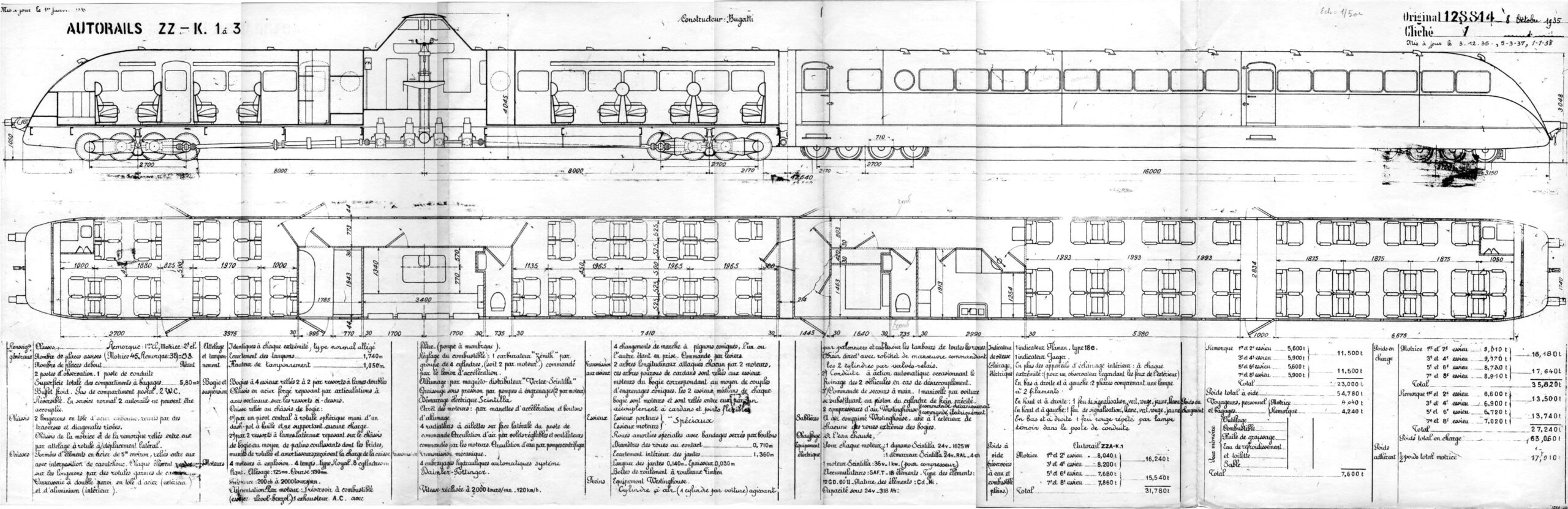

The construction of the Bugatti automatrices followed conventional railway wagon methods. The ladder frame chassis had two longitudinal steel channels with cross members. The bodywork was built on a frame, much like a Bugatti automobile.

The engines were placed transversely in the centre of the vehicle and used a Daimler-Benz automatic hydraulic converter which then delivered the drive by shafts to an axle of each of the two eight wheel bogies.

In a two engine WGL one engine drove a single axle of the front bogie, and the other engine one axle of the rear bogie. In a four engine WR the drive was similarly distributed with two engines driving one axle of one bogie and the other one axle of the other bogie. This can be seen in the diagram above.

In late manufacture WLG automotrices a Cotal gearbox was sometimes used.

If the railcar was one with two or three cars then only one of those would be powered, in the case of the three car set it would be the central car.

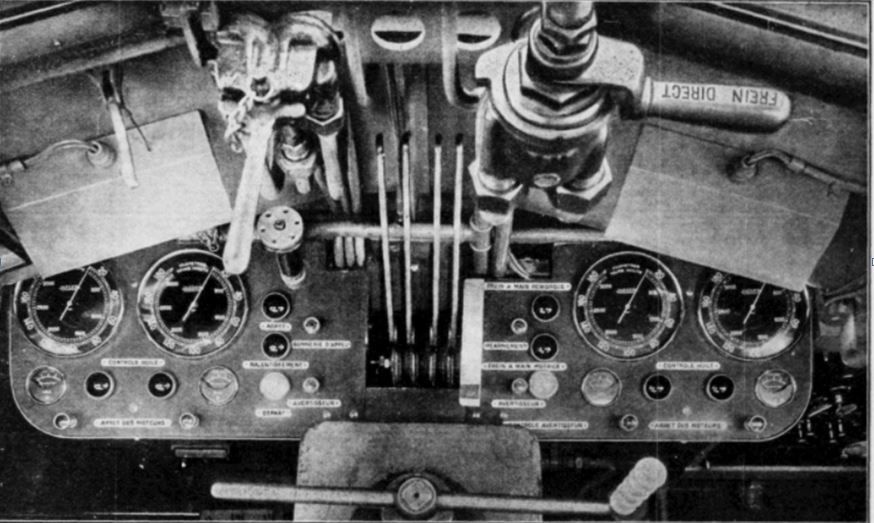

The brakes were drums mounted in each wheel with all eight wheels in each bogie having a brake fitted. These brakes were actuated by cables through an ingenious system that routed the cables to the centre pivot of the bogie, and thence, as viewed from the top, out in an “X” layout to each pair of wheels, and then to each wheel.

Ettore Bugatti was not a fan of hydraulic brakes and though this might seem a bit odd to modern readers it makes perfect sense to those of us who have spent time driving classic cars with single circuit hydraulic brakes. All it will take is one experience of a hydraulic failure and the need to use the cable operated handbrake along with changing down through the gears to stop the car to convince you that Bugatti’s dislike of hydraulic brakes was in fact quite sensible.

Bugatti wanted to ensure that their railcars delivered a quiet and jolt free ride and to this end decided that they needed to put an insulating layer of rubber compound between the wheels and the bogies with their leaf spring suspension. A railway wheel is not a one-piece unit but has a steel centre onto which is press fitted a steel flanged tyre. This tyre is fitted onto the wheel by heating it up to expand it and then press fitting it onto the wheel, so as it cools it contracts and the tyre is firmly attached to the wheel.

Bugatti decided that to get insulating rubber into his wheels that a vulcanized rubber layer could be placed in each wheel to absorb vibration between the rails and the bogie. Achieving this required some sophisticated engineering and it was something that Bugatti patented. That vulcanized rubber layer was located in each of the wheels and it had to withstand the heat of normal operation and especially braking: Bugatti accomplished that successfully.

The driver of the automotrice was placed in the centre of the car directly above the engine compartment. He stood on a platform in the cockpit with his head up in the cupola mounted into the roof. This meant he had and equally good view regardless of which direction the railcar was traveling. This also kept the length of control rods and cables as short as possible.

Having the driver’s cupola above the roof height meant that the height of the roof of the passenger compartment of the automotrice needed to be lower than on a conventional railway passenger carriage. Railway locomotives and rolling stock have to fit within the dimensions of the “loading gauge” for that particular railway. This is so they will fit through tunnels and under bridges and signal systems etc.

The Bugatti railcar was designed to provide a sufficient internal roof height for passenger comfort, but it was also made to reduce the railcar’s frontal area so that combined with its streamlined shape the automotrice would present minimal wind resistance.

Bugatti made and sold 69 of the twin engine WLG railcars and 19 of the four engine WR making a grand total of 88 produced, most between 1933 until 1939. Two may have been constructed after the war.

Of the 88 automotrices, to the best of our knowledge, only one has survived. It is on display at La Cité du Train in France. This is a WR, as used to set the world speed record, and is a beautiful example of the Bugatti “Pursang”.

Ettore and Jean Bugatti’s venture into the design and manufacture of railcars was quite probably the thing that saved the company from descent into bankruptcy and oblivion. It was a wise and well planned move and although it was an enormous gamble it paid off.

Often when we read about Bugatti venturing into making railcars it has been claimed that it was only done to use up surplus engines left over from Bugatti Royales that were never ordered. Given the designs that Ettore and Jean created and the sheer number of railcars built this seems an unlikely explanation and it tends to lead the reader to imagine that the Bugatti railcars were an inexpensive afterthought: that these were only created to use up excess engines.

The reality appears to be that Ettore and Jean had a great vision for entering into the realms of rail transportation and they fulfilled that vision in a most extraordinary way. What they built were not cheap rattle wagons but expensive, brilliantly designed and wonderfully built high speed thoroughbred rail vehicles: perhaps even pioneers of the high speed rail that we have today.

These might well have been Ettore and Jean Bugatti’s greatest achievement, and yet least remembered.

The Definitive Book on the Bugatti Automotrice

If you would like to discover more detail about the Bugatti automotrices then the book to obtain is titled: “Automotrices Bugatti, Les Pursang du rail” by Eric Favre.

This book has been self published by Eric Favre and comprises 336 pages, with over 400 illustrations.

U.S. customers, can order direct from Donald Toms, [email protected], 941-727-8667, Florida.

For customers in Europe and elsewhere in the world for further information and to order contact Eric Favre: [email protected]

Picture sources: Pictures used in this post are, to the best of our knowledge, original to Bugatti, or the SNCF.

Jon Branch is the founder and senior editor of Revivaler and has written a significant number of articles for various publications including official Buying Guides for eBay, classic car articles for Hagerty, magazine articles for both the Australian Shooters Journal and the Australian Shooter, and he’s a long time contributor to Silodrome.

Jon has done radio, television, magazine and newspaper interviews on various issues, and has traveled extensively, having lived in Britain, Australia, China and Hong Kong. His travels have taken him to Indonesia, Israel, Italy, Japan and a number of other countries. He has studied the Japanese sword arts and has a long history of involvement in the shooting sports, which has included authoring submissions to government on various firearms related issues and assisting in the design and establishment of shooting ranges.