The “Land of Oz” and a Plethora of Rail Gauges

There’s a song that says the “Land of Oz is a very funny place…” and some people like to call Australia the “Land of Oz”. Its true that, back in the 1960’s when I first went there, it seemed a funny place indeed. Instead of nickels and dimes there was the “deena” (a shilling), “zac” (sixpence), and the “trei” (threepence). Beer glass sizes each had a name; a “pony” being the smallest, a “midi” being middle sized, and a “schooner” being the large one that would cause you to sail out of the pub in a contentedly inebriated state.

Australia was a nation that had grown up as a group of independent colonies that had become states, each one self-governing and responsible for its own affairs up until Federation at the turn of the century when a Federal Australian Government was created to look after defense and international affairs.

The upshot of this independence was that each state controlled the construction of its own rail system. This sounds fine until you realize that, unlike the Americans and Canadians who were able to agree what gauge railway networks they were going to construct, it wasn’t like that in Australia. The State of New South Wales was the first of the British convict settlements and were very British in their loyalties. So when it came to constructing a rail network they opted for British standard gauge 4’8½”. To the south west of New South Wales was the State of Victoria which, despite being named after the Queen of Britain, had an Irish railway engineer, and he, according to popular legend, was not going to build Victoria’s rail network in British Standard Gauge, but chose Irish broad gauge of 5’3″. To the west of Victoria was the State of South Australia and, faced with Victoria choosing Irish 5’3″ they decided to go with that. The fly in the ointment however was that when they wanted to build a rail line from South Australia to the center of Australia at Alice Springs, and thence to the northernmost town of Darwin, it was an expensive and difficult thing to do, very expensive in broad gauge, so they settled on “Cape Gauge” of 3’6″ as used in much of Africa.

To Build a Rail Line Across the Nullarbor Plain

In all these administrative decisions no-one ever expected to build a rail line that would connect the heavily populated eastern states with the State of Western Australia. Not only was the distance huge, but it would require constructing the rail line across the water-less expanse of the Nullarbor Plain. Instead of a rail line to remote Western Australia there was a shipping service instead and people would travel by ship to get there and back again. This should not be imagined as a pleasant cruise on smooth waters. The journey from Western Australia to the eastern states required the ships to traverse the Great Australian Bight, which features some of the roughest seas on earth. I’ve crossed it in a 45,000 ton ship equipped with stabilizers, and to move around required moving hands first, on the handrail, and then feet: passengers were not allowed outside on deck for fear of going for an impromptu swim. Waves were big enough to cause “thrashing” as the propellers were lifted out of the water.

It was not until after Federation in 1901 when Australia became a nation, as opposed to being a collection of colonies, that the need for a rail line to connect the East to the West was really thought necessary. One of the promises that had been made to the State of Western Australia to persuade them to join the Federation was that a rail line would be constructed to connect them to the rest of Australia, and eliminate the need for sea sickness pills.

The plans for the Trans-Australian Railway were begun in 1907 with legislation to launch the project. This was in part spurred on by the threat of the Great War that the politically aware could see coming. 1907 was the year that Australian poet Henry Lawson wrote “Every Man Should Own a Rifle”, referring to the need for every man to have a rifle for the defense of newly formed Australia.

Every Man Should have a Rifle

So I sit and write and ponder, while the house is deaf and dumb,

Seeing visions “over yonder” of the war I know must come.

In the corner – not a vision – but a sign for coming days

Stand a box of ammunition and a rifle in green baize.

And in this, the living present, let the word go through the land,

Every tradesman, clerk and peasant should have these two things at hand.

No – no ranting song is needed, and no meeting, flag or fuss –

In the future, still unheeded, shall the spirit come to us!

Without feathers, drum or riot on the day that is to be,

We shall march down, very quiet, to our stations by the sea.

While the bitter parties stifle every voice that warns of war,

Every man should own a rifle and have cartridges in store!

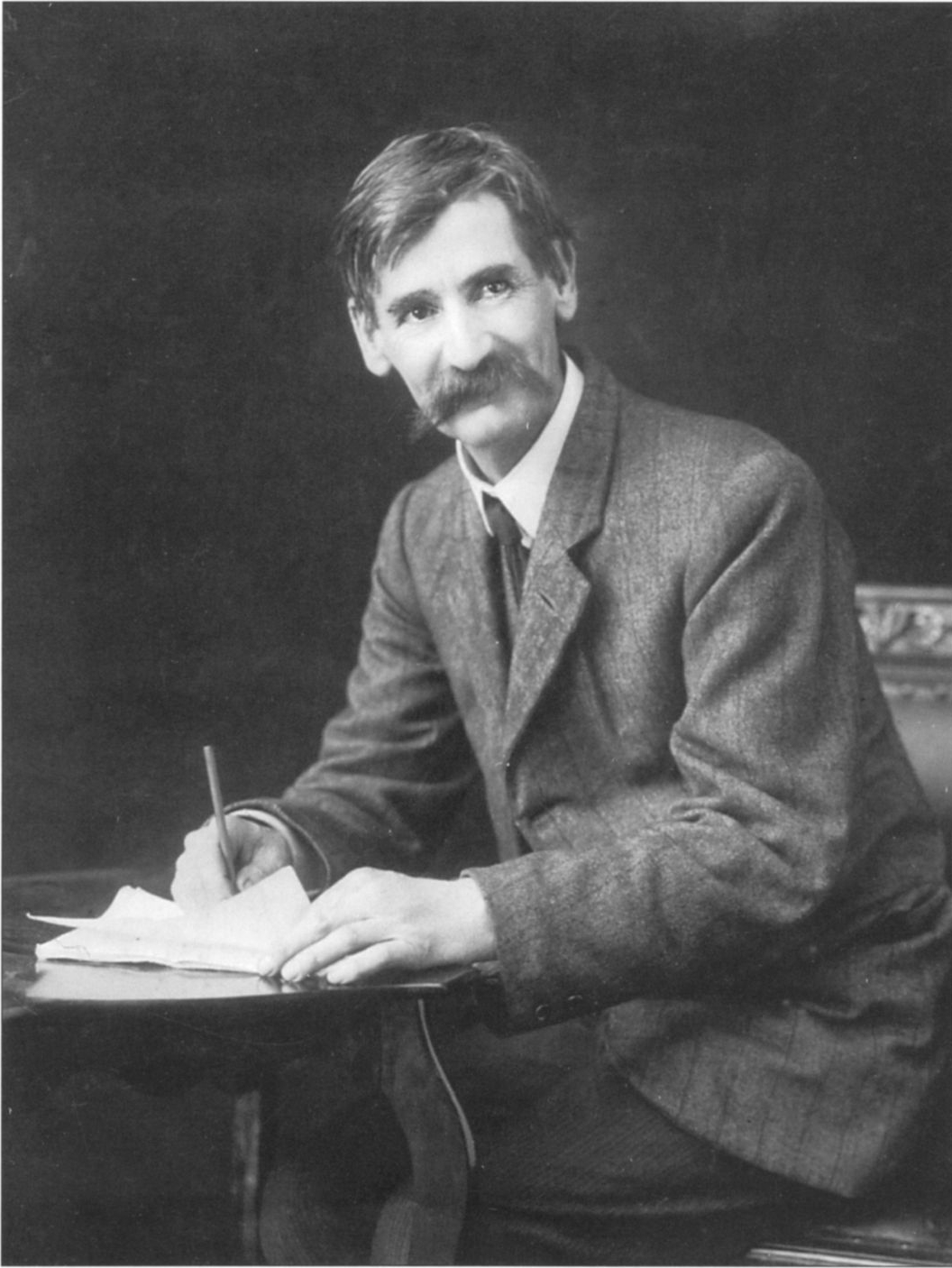

Henry Lawson

With the impetus to fulfill the promises made to Western Australia, and with the prospect of a Great War looming, the Australian Government had the surveying completed and decided on a Standard Gauge 4’8½” rail line that would run from the town of Port Augusta in South Australia to the gold mining center of Kalgoorlie in Western Australia. This covered a distance of 1,063 miles (1,711 km) and actually connected the 3’6″ line from Adelaide in South Australia to the 3’6″ line in Kalgoorlie, Western Australia as the first step in establishing a standard gauge rail line fully connecting the east to the west, something that would not be completed to include the state capital cities until 1970.

Building the Transcontinental Railway

The name “Nullarbor” is not an Australian aboriginal word for tree-less plain. It is Latin; Null=None, and Arbor=Trees. The Nullarbor is without trees because it is without water. Therefore to build the Transcontinental Railway required bringing in everything that would be required all along the route. This meant food, water, and all supplies needed for keeping the workers in good shape as well as the materials for building the rail line.

Work began in September 1912 from Port Augusta and soon after another team began work from Kalgoorlie in Western Australia. They met and joined the two sections of line at Ooldea on 17 October 1917, even as the Great War, foreseen by Henry Lawson a decade earlier, was raging.

Constructing the rail line was not the end of the job however. A rail line requires regular maintenance, and that meant that settlements had to be established along the route for the fettlers (railway track maintenance workers).

As the fettlers were going to need to live and work on the line permanently this also meant that those settlements would require housing for the fettler’s families. In turn this required provision of schools for the children, and provision of shops so that the families could buy their daily needs.

Settlements were established along the Transcontinental Railway for fettler’s families. Teacher training in South Australia and Western Australia ensured that teachers were trained to work in “one teacher schools” such as those on the Trans-Line and graduate teachers were on contract with the state education authorities to go and work wherever they were sent, including to schools on the Trans-Line.

The Tea and Sugar Supply Train

Life in the Nullarbor fettler’s settlements could have been a bleak existence but it was made pleasant for the families who lived there by the provision of the weekly supply train which was affectionately known as the “Tea and Sugar”. The Tea and Sugar was more than just a supply train however, it fast became the glue that held the settlements together. It often had a trained nurse on board with her own facilities in a carriage to look after the medical needs of men, women and children. There were supplies, mail, and a butcher’s shop all coming once per week. And once per year Santa Clause would arrive on the Tea and Sugar with gifts for the children.

Perhaps the best way to get a picture of the life of the people of the fettler’s settlements on Australia’s bleak Nullarbor Plain is a short film courtesy the Australian National Film and Sound Archives.

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0vAh-p0-cPA” /]

The Tea and Sugar continued to run its weekly mission up until advances in railway track made the maintenance so minimal that the fettler’s settlements could be closed down. Welded rails and concrete sleepers (ties) worked together to remove the need for people to spend their lives out on the Trans-Line. Yet despite how isolated that life looks, there were those who did not want to leave when the settlements were finally closed. Sadly for them it was not possible for them to stay however, as the Tea and Sugar ceased its runs in 1996 and without it there was no way for people to remain out on the hot and water-less Nullarbor Plain.

While it was running the Tea and Sugar was an Australian icon. Now it is gone it still has a placed etched into Australia’s history.

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fPnnO0EH6ms” /]

Jon Branch is the founder and senior editor of Revivaler and has written a significant number of articles for various publications including official Buying Guides for eBay, classic car articles for Hagerty, magazine articles for both the Australian Shooters Journal and the Australian Shooter, and he’s a long time contributor to Silodrome.

Jon has done radio, television, magazine and newspaper interviews on various issues, and has traveled extensively, having lived in Britain, Australia, China and Hong Kong. His travels have taken him to Indonesia, Israel, Italy, Japan and a number of other countries. He has studied the Japanese sword arts and has a long history of involvement in the shooting sports, which has included authoring submissions to government on various firearms related issues and assisting in the design and establishment of shooting ranges.