Fast Facts

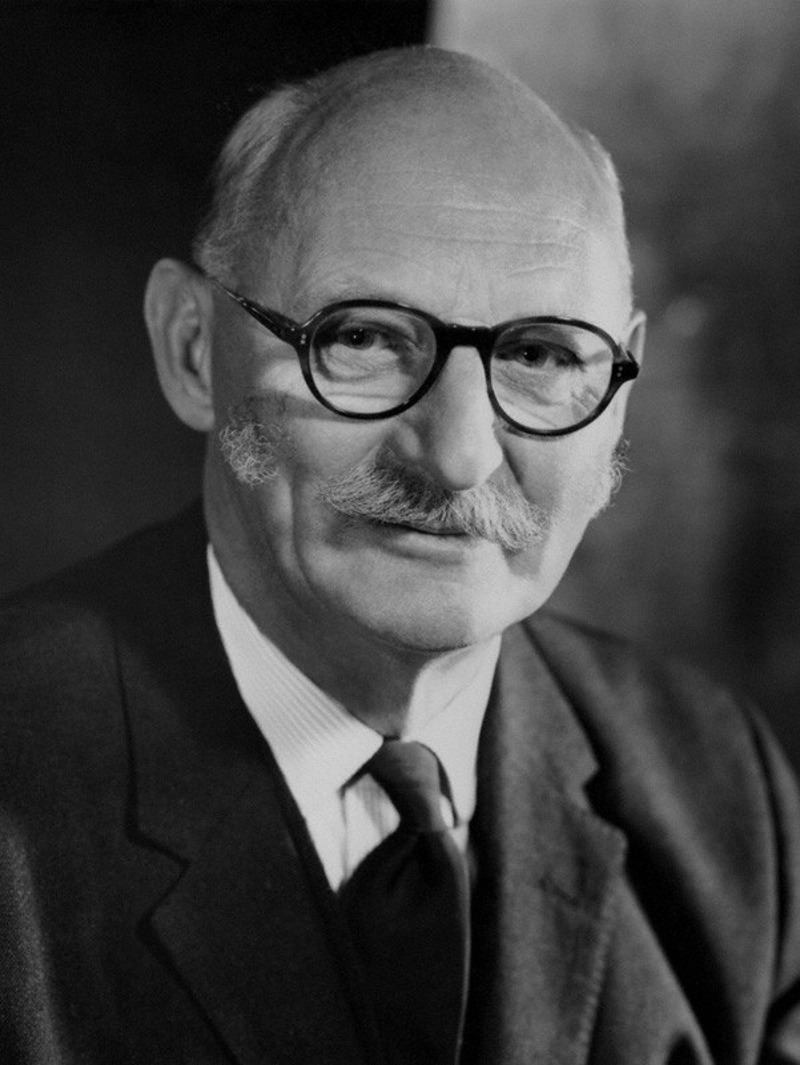

- Christopher Cockerell is best known for his invention of the hovercraft, although before that he believed that his greatest achievements had been while working for Marconi developing radio and radar technology.

- When Cockerell first showed his hovercraft to the British Government the armed services all decided that they weren’t interested in it – but because they didn’t want the idea to fall into foreign hands they declared Cockerell’s invention to be Top Secret, thus preventing him from getting commercial backing to make his invention a reality.

- A couple of years after that the British Government relented, de-classified the hovercraft, and helped Cockerell get backing from private enterprise to make the invention a commercial success.

- In later life Christopher Cockerell turned his inventive mind to the idea of generating pollution free electrical power by harnessing the energy of sea waves.

Fathers are often hopeful for their children to pursue careers that will make for a nice stable and adequate income for their future lives. So if a son comes to his Dad and says “Dad, I want to be an artist” the Dad in question might just be a tad concerned, because artists historically don’t make much money – not usually until after their deaths.

But this was not the case for Christopher Cockerell, quite the reverse: his Dad really wanted him to become an artist, but young Christopher, to his Dad’s dismay, wanted to become an engineer.

Young Christopher’s Dad you see was Curator of the Fitzwilliam Museum of Cambridge University. The Museum being dedicated to Art and Antiquities, and he was friends with a number of famous artistic people including George Bernard Shaw, Joseph Conrad, and T.E. Lawrence (aka Lawrence of Arabia).

It is recorded that the young Christopher was fascinated by T.E. Lawrence’s 1,000 cc V-twin Brough Superior motorcycle, at which his horrified father was said to have exclaimed that he was “No better than a garage mechanic”.

But young Christopher did not want to follow in his father’s footsteps, so his father enabled him to study at Peterhouse Cambridge where he achieved his matriculation studying mechanical engineering. Christopher worked for a while and then went on to enrol at the University of Cambridge in 1934 where he studied radio and electronics. It was a decision that would make a significant impact for his nation in the war that was to come.

From Cambridge Christopher Cockerell went to work for the Marconi electronics company and was involved in the development of radar and radio location technology. These technologies were to prove to be war winning during the Battle of Britain, and in lesser known battles such as the naval battle of North Cape in which radar, including location technology and fire control radar proved decisive in enabling the joint British/Canadian/Norwegian task force to locate the German Battleship Scharnhorst and sink it in the abysmal weather conditions of the Arctic Night on Boxing Day of 1943.

Christopher Cockerell regarded his time at Marconi as having been one in which he was able to make a great impact on his country and her future. He emerged from that time with thirty six patents for which Marconi paid him £10 for each one back in a time when that amount equated to be about one weeks wages for a working man.

Cockerell was restlessly inventive: and so he ultimately became bored with the routine at Marconi after the wildly innovative war years. He really wanted to set up his own business that would afford him the time and money to work on new inventions, and that opportunity came five years after the end of the war. In 1950 Christopher Cockerell and his wife Margaret received an inheritance from her father when he passed away and it was sufficient for them to purchase a boat yard in Norfolk: this being not far from Christopher’s family home in Cambridgeshire.

Cockerell had an idea that had been on his mind for a period of years, and that was for a craft that could float on a cushion of air, enabling it to traverse land, marsh and water with equal ease: a craft that would cross these types of terrain without having to drive across them or float, both of which created a lot of drag and used up energy and fuel. A craft that only had to contend with air resistance could be fast like an aircraft, and fuel efficient.

This new type of craft did not yet have a name but Cockerill decided that since it would hover over the surfaces it traversed it might be best described as a “hovercraft”.

Although others had tried the idea of using some sort of air cushion to make a craft such as a boat experience less water resistance Cockerell’s idea was to create a blast of air around the perimeter of the craft so that much of the air directed downwards would be directed from the perimeter into the area under the craft thus creating a higher pressure underneath it and having that air pressure create lift.

In a quite inventive schoolboy style Cockerell got two empty tins (cans), one slightly larger than the other. For the smaller can he used a “Kit-e-Kat” cat food can, and for the larger one a Lyons Coffee can. After giving the Kit-e-Kat can a thorough wash so it didn’t smell of cat food, he rigged up the cans one inside the other with the outlet from the house vacuum cleaner blowing air into the narrow cavity between the large and small one.

This rig was then set up over the kitchen scales to measure the down-force using the can arrangement by comparison with the energy that was created by the vacuum cleaner blower on its own. Armed with knowledge of the differential between the two, Cockerell then sat down and used his head to do the math. Back in those days we did not have natty little electronic calculators nor were there computers, but we each had a brain, and with the assistance of logarithm tables and perhaps a slide rule, complex math was accomplished, and the power to weight ratio required could be calculated.

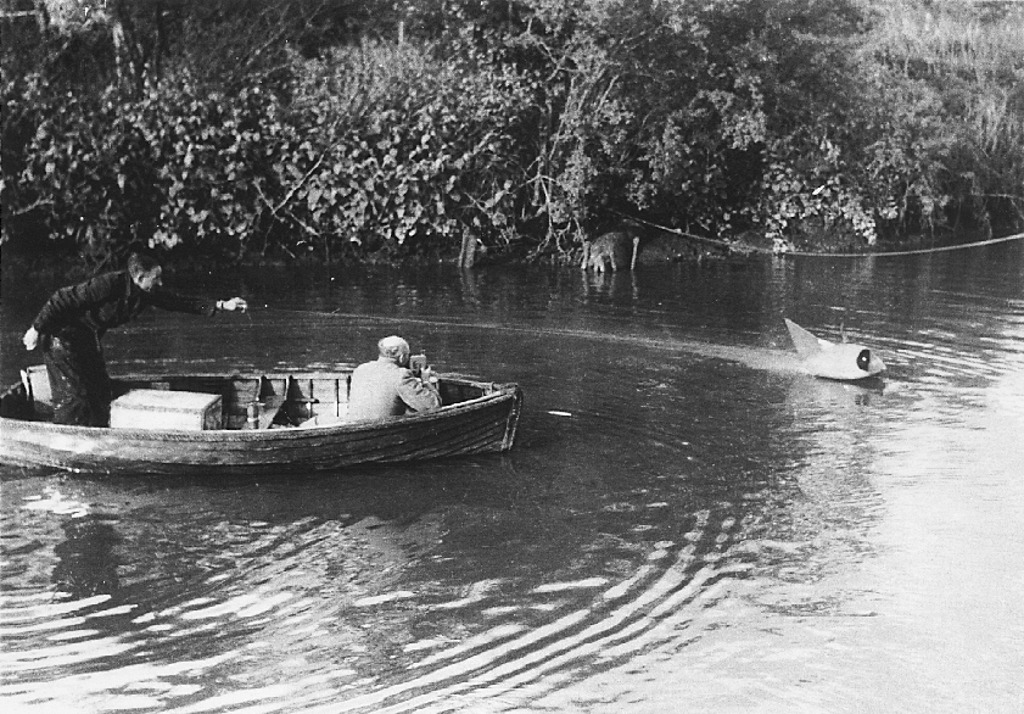

Cockerell discovered that his unique concept using a ring of air was indeed promising and so he took the next step and built a working prototype model which he made using balsa wood, a soft and light wood that is easy to cut and shape so its commonly used by model aircraft and model boat makers.

The working model was tested by Cockerell with the help of an old friend from his Marconi days Micheal Gregory. Back in the early 1950’s the common way to control powered model aircraft and boats was to use a control line and so that is how this model hovercraft was operated. Cockerell made a number of models and then arrived at the inevitable, and expensive, next step: a full size prototype.

To move towards the goal of building a working prototype, and then moving into production, Cockerell had arrived at the make or break point for the fulfillment of his dream. He started his own company in 1955 and called it Ripplecraft, and then began looking for financial backing.

Given the quite obvious potential of his hovercraft Cockerell approached the British Government, and they sent him to talk with representatives of the British military. The Royal Navy told him his invention was an aircraft not a boat: so they weren’t interested. The Royal Air Force told him it was a boat and not an aircraft: so they weren’t interested. And the Army just told him they weren’t interested.

After this string of rejections Cockerell was about to be subjected to one more obstacle to stop him from moving forward with this project.

American President Ronald Reagan once said that the eight most terrifying words in the English language are “I’m from the government” and “I’m here to help”. Christopher Cockerell was about to find that out the hard way – by personal experience.

The British Government decided that his hovercraft technology needed to be kept “hush-hush” so foreign governments didn’t get their hands on it, so they made the project a state secret. Thus banning Christopher Cockerell from developing it further.

The classified status of his hovercraft was not lifted until 1958, and at that time the British Government agency, the National Research Development Corporation (NRDC) was at last willing to take on the job of assisting Cockerell in creating a full size working prototype.

The NRDC awarded the contract to build this new hovercraft, the SR-N1, to Saunders Roe, famous for their flying boats (seaplanes) that had been a backbone of air travel to Britain’s overseas colonies such as Hong Kong, back in the days before such places had airports.

The SRN1 (Saunders Roe Nautical 1) made its maiden “flight” on 11th June 1959, and on 25th July that year Christopher Cockerell with two pilots in control made the first crossing of the English Channel by hovercraft.

Here is a video showing the history leading up to this event courtesy “Naked Science”

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-ZvSQsIwXmg” description=”Christopher Cockerell and the Hovercraft” /]

During that English Channel crossing the seas had become quite choppy and Christopher Cockerell realized that the ride height above the waves needed to be increased. He figured out a way to accomplish this by fitting a rubber skirt around the hovercraft which raised it up nicely and made it far better at managing waves in rough seas.

From that relatively small beginning of SR-N1, the technology of the hovercraft has gone on and they can now be found all over the world made by various companies.

You can find some of these at the Hovercraft Museum website.

And there is a summary listing of a number of hovercraft types on the jameshovercraft.co.uk website.

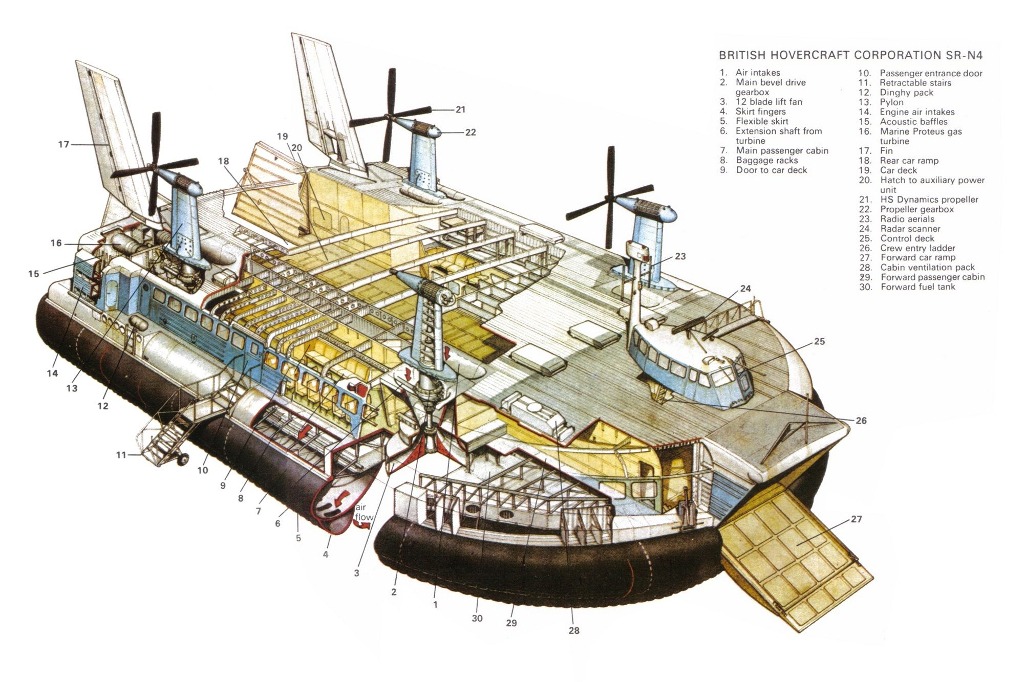

The largest of the British hovercraft was the SR-N4 which were used on the Dover to Calais route across the English Channel for 40 years, until the building of the Channel Tunnel and initiation of a train service directly from Britain to France and thence to Europe and North Africa.

The SR-N4 could cruise at 70 mph from the British seaside town of Wallasey and make the 40 mile Channel crossing in 20 minutes. It was able to carry approximately 380 passengers and 40 motor cars.

The SR-N4 was 185 feet long, 91 feet wide, and weighed 300 tons.

Christopher Cockerell was knighted for his services to his country in 1969.

There were many and varied types and sizes of hovercraft from the large SR-N4 down to a home made one based on a British Morris Mini motor car: and nowadays hovercraft are being built all over the world including in Russia where the technology has great advantages in safely crossing ice covered landscapes and frozen, or semi-frozen lakes and rivers.

There are military hovercraft also with the US Marines having more than 200 of them.

As the sheer scale of the use of his invention increased Christopher Cockerell made the move to leave the invention he had fathered and he moved on to work on a new invention; wave power, the pollution free generation of electrical power using the power of sea waves. This device became known as the Cockerell Raft.

He remained inventive in his later years and ultimately passed from this life on 1st June 1999 at the age of 88 years, in the British coastal town of Hythe (Home of the Romney Hythe and Dymchurch Railway).

He had lived a full life, fulfilled his dream, and made a great contribution to his nation in the Second World War by creating and developing technology that was used to stop the Nazi take-over of Britain.

(Feature image at the head of this post is of the Hover Travel hovercraft that operates between Southsea on the British coast and Ryde on the Isle of Wight).

Jon Branch is the founder and senior editor of Revivaler and has written a significant number of articles for various publications including official Buying Guides for eBay, classic car articles for Hagerty, magazine articles for both the Australian Shooters Journal and the Australian Shooter, and he’s a long time contributor to Silodrome.

Jon has done radio, television, magazine and newspaper interviews on various issues, and has traveled extensively, having lived in Britain, Australia, China and Hong Kong. His travels have taken him to Indonesia, Israel, Italy, Japan and a number of other countries. He has studied the Japanese sword arts and has a long history of involvement in the shooting sports, which has included authoring submissions to government on various firearms related issues and assisting in the design and establishment of shooting ranges.