Michèle Mouton has gone into history as one of the greatest rally drivers of all time – and one of greatest women drivers. She ascended up the ranks in international rallying and drove in the demanding Group B. She was also a member of a class winning all women team at the prestigious 24 Hours Le Mans.

Described by Nikki Lauder as “Superwoman” and by Stirling Moss as “One of the best” Mouton overcame obstacles and hardship to achieve what few can manage whether man or woman.

Fast Facts

- Michèle Mouton came into rallying quite by accident when she was invited to be a co-driver for a friend.

- Michèle’s parents soon came to realize that their daughter was becoming increasingly keen to see if she could make a career of rallying and so her father offered to buy her a competitive car and finance her competitions for a year to see if she could make a success of it.

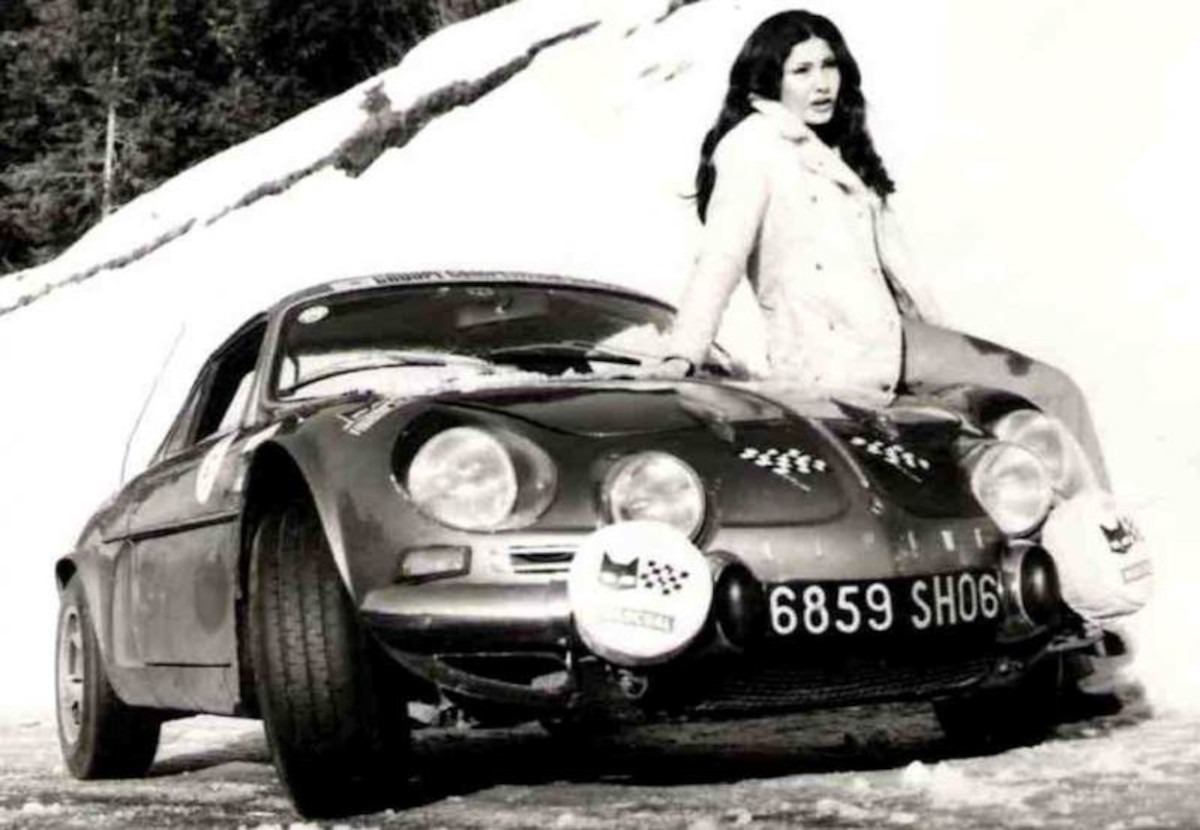

- The car, wisely chosen, was an Alpine Renault A110.

- Once launched into rallying as a driver Michèle proved herself to be a gifted and determined competitor.

- Michèle was first signed by Fiat and then was called by Audi Sports who were looking for highly skilled drivers to campaign their new Audi Quattro rally cars.

- Michèle was driving for Audi into the demanding Group B era before signing with French car maker Peugeot. She retired when Group B ended.

The story of Michèle Mouton is one filled with a passion for life, for people, and for living life beyond her comfort zone, a life spent experiencing the truth of the statement “the best discoveries are made outside your comfort zone”.

It is also a story of her parents courage and faith, especially her father, in helping their daughter to live her dream despite the dangers inherent in the pursuit of that dream. Michèle’s dream was to go where few women had gone before, to put in the best she could muster, and to accept the outcome of her commitment whatever that might be.

But that dream began small, initially perhaps even insignificant. Michèle Mouton as a young woman loved dancing, including ballet, and it was really by an accident of circumstances that she was given her first taste of motorsport and the surge of adrenaline that accompanies living on the edge of control.

Michèle had her first taste of driving her father’s rather agricultural Citroën 2CV at the tender age of fourteen, and she loved it, and when she was old enough obtained her driving license. But at that stage of her life a car was a fun thing, and good for providing the freedom to go where you wanted to go when you wanted to go there.

It was in 1971 when Michèle was twenty that she and a friend had entered a Rock ‘n Roll dance competition and it happened that he mentioned he was going to do a “rally”. Interested Michèle asked him what was this “rallying”, and as she found out more, and saw and began to experience rallying that her interest became deeper.

By 1972 Michèle had been invited by friend Jean Taibi to be his co-driver for the Tour de Corse, and in 1973 she was his co-driver for the Monte Carlo Rally, which was the first World Rally Championship event.

Michèle’s father could see that his daughter had found something she loved, so he decided to intervene in the best way he knew how.

Mr. Mouton had lived through the Second World War and had finished up as a prisoner of war for five years. The World War had destroyed many lives, and damaged the ambitions and opportunities of many and Michèle’s father had been one of them. He was a motorsport enthusiast, and he had emerged from the war with a property and business growing jasmine and roses to supply to the French perfume industry.

The war had denied him the opportunity to fulfil his own ambitions as a young man: but he had the resources to help his daughter attempt hers, and the wisdom to understand how to go about it.

He could see that for his daughter to launch into a career in motorsport that she would need to be the driver, not the co-driver, and that she would need to field her own car, and experience the responsibility of using it in the best possible way.

So Michèle’s father offered to buy her a car that would be competitive and provide for the expenses incurred in maintaining it and competing with it for one year, by the end of which time Michèle would know if this was really the career she was going to commit to.

So Michèle paused her legal studies and embarked on what would indeed become her career for the coming years.

The one year deadline gave Michèle the understanding and motivation to put her all into making a success of this extraordinary gift that her father had trusted her with, it was as if he was giving her the opportunity that the war years had denied to him.

The car Michèle and her father decided on was an Alpine Renault A110. It would prove to be a little blue road-rocket that would launch Michèle Mouton on her journey to the top levels of motorsport: but of course back then neither Michèle nor her father had any idea just how close to the top she would ascend.

The Adventure Begins

Michèle Mouton made her debut as a rally driver in the 1973 Rallye Paris – Saint-Raphaël Féminin driving her new Alpine Renault A110. She then went on to compete in the Tour de France Automobile and a number of other events. In 1978 she would win the event.

In 1974 Michèle would make her World Rally Championship debut driving her Alpine A110 in the Tour de Corse. She finished in twelfth place. Her entry in the World Rally Championship served to put to rest a rumour that the reason she had been doing so well in the events she entered had been because of modifications to her A110 that were against the rules. For the WRC competition all cars, including Michèle’s, were subject to strict scrutineering, and her A110 passed with flying colours – so the rumours were proved to be false.

At the end of 1974 Mouton had established a high reputation as a female driver winning both the French and European Ladies’ Championships.

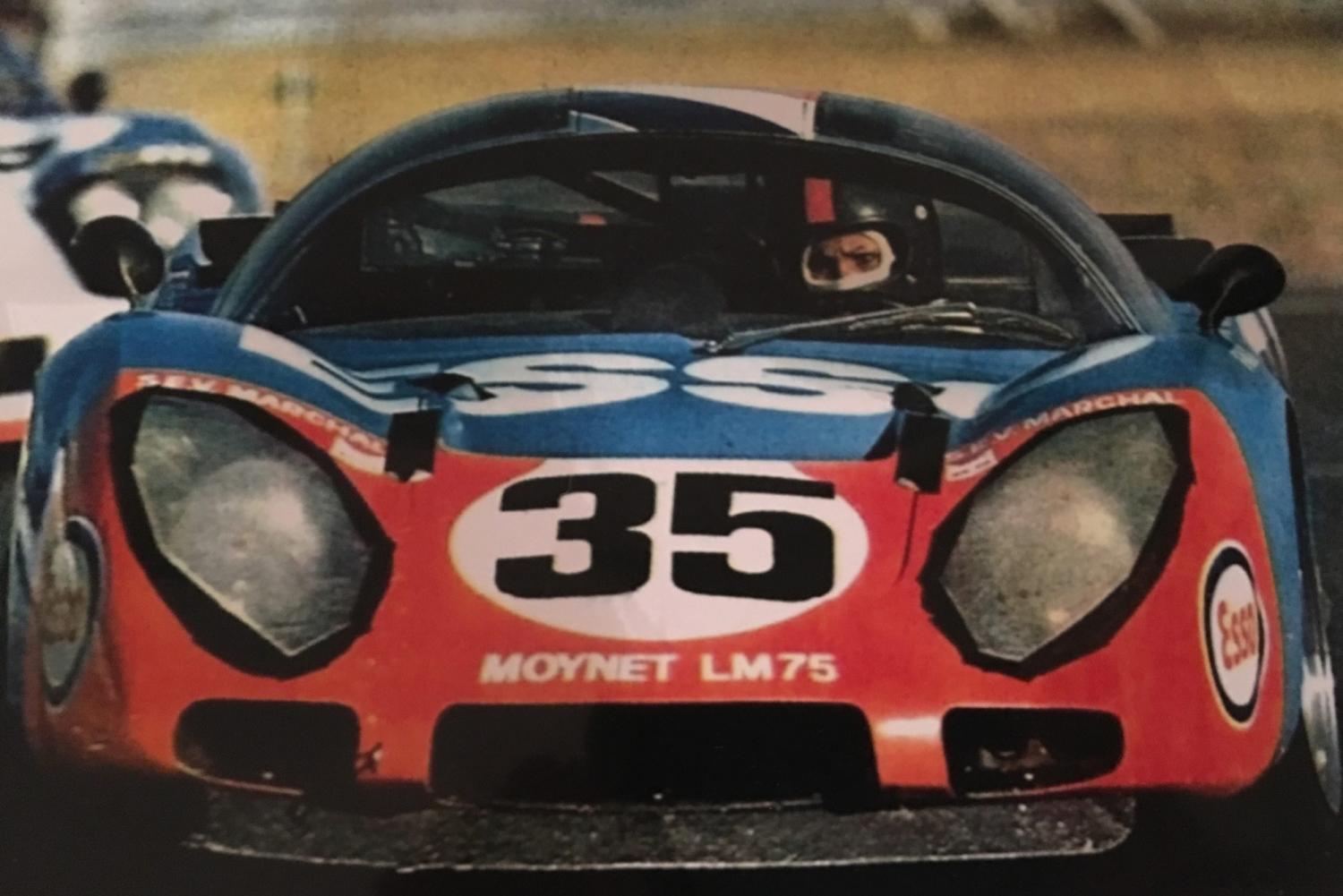

Her reputation began opening doors for her and she was invited to join Christine Dacremont and Marianne Hoepfner in the 1975 24 Hours Le Mans. This team was assembled by André Moynet, a French test pilot, politician, motorsport enthusiast, and war hero. Moynet had created his Group 5 Moynet LM75 prototype sports car based on a Chappe et Gesselin chassis and powered by a four cylinder two-litre (1994 cc) Simca-JRD engine with a Porsche transmission.

Michèle Mouton proved her worth and demonstrated some of the creative depth of her abilities when the rain began. Her car was at that time running on dry weather “slicks” and the conventional wisdom of the pit crew was to get her into the pits to change to wet weather tyres – but Michèle was reluctant to do that, she was happily passing lots of people and managing the slippery conditions quite comfortably. She later likened it to dancing and no doubt her rally experience on loose slippery surfaces at high speed served her well.

So she incorporated rallying and ballet into her race-track driving along with an ear for the engine – the tachometer had failed and she had to gauge the engine rpm by sound.

To André Moynet’s delight the team won the Group 5 two-litre prototype category, which was quite apropos as 1975 had been declared to be the United Nations International Women’s Year.

The following year Mouton obtained sponsorship from French oil company Elf and she obtained an eleventh place outright in the Monte Carlo Rally. Alpine debuted a new model, the A310 and Michèle campaigned one in the Tour de Corse. She was forced to retire however.

1977 brought a new opportunity for Michèle Mouton when she was offered a place on the Fiat team alongside Jean-Claude Andruet. This meant adapting to a completely different car, the Fiat 131 Abarth.

Mouton had up to this point been rallying in the Alpine A110 and A310, both diminutive rear engine rear wheel drive cars, and at Le Mans she had been driving another quite small two-litre mid-engine racing car: so the Fiat 131 Abarth was a rather heavier and different handling car by comparison.

In the 1970’s power steering was not usual, and especially not for competition cars. If you look at pictures of front-engine sports cars of this era, you’ll note that the steering wheel is often of fairly large diameter and there is a reason for this, a reason one quickly discovers when one has to do some slow speed maneuvering such as parking, the steering is heavy. The heavy steering tends to give very precise feel and control, but motorsport drivers tended to wear driving gloves, and with good reason.

For Michèle Mouton the heavy steering proved to be difficult simply because as a woman she did not have the sheer strength required to manage this front-engine heavy steering comfortably. Her hands would tend to blister and bleed, which is not conducive to a driver maintaining concentration.

Despite the difficulties Mouton did well in that car and had the opportunity to compete in a mid-engine Lancia Stratos HF and outside her role with Fiat in a Porsche Carrera RS. The Porsche seems to have suited Mouton well and she obtained victory in the 1977 RACE Rallye de España and second place in the Tour de France Automobile. Her final result for 1977 was second place in the European Rally Championship. She was ascending into the ranks of the top drivers in Europe.

1978 saw Mouton behind the wheel of what she described as the “truck”, the Fiat 131 Abarth, which she hammered to victory in the Tour de France. In the Rallye d’Antibes she obtained second place, again demonstrating she had mastery over the “truck”.

That year Mouton gained fifth in the European Rally Championship, and fourth in the FIA (Fédération Internationale de l’Automobile) Cup for drivers. Then in 1979 she placed second in the French Rally Championship.

By this stage of her career Michèle Mouton had competed at exactly the same level as the men drivers and had wrought success on equal terms with them. Her reputation was well established, and no doubt her father was delighted with the way she had worked to the very best of her ability to achieve the results she had in the unforgiving world of top-level motorsport competition.

It was at this stage, in 1980, that Michèle received a surprise phone call from German car maker Audi with an offer to have her drive for their Audi Sport team in the coming season. She decided to accept, and the effect of that decision would be to launch her into a whole new style of car and the learning curve that accompanied it.

Audi Sport

Audi had entered into motorsport in order to build up the brand image, not only in Europe but also internationally in such places as Australia where the brand was not well known during the 1970’s.

Audi had realized that they would have best chance of success if they went rallying and came up with a car that would trounce the competition.

Audi’s engineers had available to them the excellent four-wheel-drive transmission system used in the Volkswagen Type 183 “Iltis. Four-wheel-drive provides a significant road-holding advantage, especially on slippery surfaces, and the engineers reasoned that it could provide a competitive advantage that might prove decisive.

This was not to be an easy thing to accomplish, and the end result was not perfect, but it certainly proved to be the technology to invest time and effort into.

The result of Volkswagen/Audi’s engineering innovation was the creation of the Audi Quattro four-wheel-drive car.

Audi-Sports looked to find the best drivers who would be able to get the best out of this new car, drivers who would be able to compensate for its shortcomings and use its strengths to best advantage.

The drivers they recruited for this high stakes enterprise included Hannu Mikkola, Freddy Kottulinsky, and Michèle Mouton.

The Audi Quattro design produced the need for specialized driving techniques to overcome its foibles and extract the best from its potential. Michèle needed to learn some Quattro specific driving techniques including the use of left-foot-braking and how to apply it where needed to make the car behave as wanted. The Quattro was very prone to understeer and left-foot-braking was one of the techniques used, often in conjunction with throttle, to move the car from understeer to oversteer or neutrality where needed.

The Quattro were powerful machines, with turbocharged engines delivering 300 hp to their four wheels.

Mouton’s first success in the Quattro was in the Rally Portugal. She was teamed with co-driver and friend Fabrizia Pons and between them they won seven stages and completed the event in a respectable fourth place.

Mouton and Pons competed in a number of events in 1980 including the Tour de Corse, Acropolis Rally in Greece and the 1000 Lakes Rally in Finland. But it was in the Rallye Sanremo that she really shone.

This rally was a mix of tarmac surfaced and gravel sections and Mouton was able to get into the lead position when the event favourite Michele Cinotto crashed, leaving Mouton to fend off the attempts by Henri Toivonen and Ari Vatanen to overtake her.

Ari Vatanen had been a bit vocal prior to his race against Mouton and had claimed “Never can nor will I lose to a woman”. This would prove to have been a statement he might have regretted, because he lost to Mouton.

Michèle Mouton had become the first woman to win a World Rally Championship rallying event. If there had been any doubts about her abilities before that there would be none after it.

Mouton did not have a trouble-free run to that victory. The Quattro had experienced problems with brake pads and she had not been able to sleep in the four hours between the end of the previous stage and the start of the final one. She recalls saying to Fabrizia “”OK, we forget everything, and we are at the first stage of the rally again, because one of us will crash.” And so Ari hit a rock, and we won the rally.”

1982 was to prove a very demanding year. Rallying had become a popular spectator sport and in the absence of crowd control over much of the roads things had become dangerous not only for the drivers but also for lemming like spectators.

We can appreciate something of the spectator problem if we realize that some spectators who were among the most lemming like would try to touch the cars as they sped past, and occasionally the impact between spectator’s hand and the rally car would result in the spectator losing a finger or three: and sometimes pit crews would find fingers lodged in parts of the car.

Mouton recognized the danger – but it was a danger that was unavoidable – so she decided that she would think of the spectators as trees, albeit trees that would move. So just as it would have been nasty to hit a tree, she drove to avoid the spectators – even the ones trying to touch her car.

Mouton and Pons had a bad start to the year when during the twelfth stage they crashed into a stone wall at about 110 km/hr resulting in a knee injury for Michèle and concussion for Fabrizia.

She also crashed in the Swedish Rally, but still emerged in fifth place.

But in Portugal the Mouton/Pons team gained no less than eighteen stage wins and an outright victory.

Mouton/Pons team made seventh in the demanding and very fast Tour de Corse, and won the Acropolis Rally in Greece, which placed her only twenty points behind the championship leader Walter Röhrl and in striking distance of the championship.

Around this time Michèle’s father was diagnosed with cancer, but he had wanted his daughter to continue to reach for her dream. So Michèle and Fabrizia campaigned in New Zealand, Brazil and the 1000 Lakes in Finland, and Sanremo.

With the points for the championship being so tight Audi Sports team decided to compete in the demanding and dangerous Rallye Côte d’Ivoire in Africa.

Just prior to the start of that event Michèle received a phone call from her mother to tell her that her father’s condition had suddenly deteriorared, and that he had passed away.

Suffice to say this was devastating news and Michèle was going to withdraw from the rally, and give up her chance of winning the championship. But her mother impressed on her that her father’s wish had been for her to continue and compete, to chase her dream: and so she did.

The Rallye Côte d’Ivoire was run in temperatures above 30°C and the heat dust and road conditions took a heavy toll on every competitor’s car. At the end of the first day Mouton and Pons completed the 1,200 km eight minutes ahead of team-mate Mikkola and almost thirty minutes of championship rival Walter Röhrl.

In the succeeding days of the rally Michèle’s car continued to manifest serious mechanical issues which whittled away at her lead: and then with about 600 km of the 5,100 km rally left she rolled her car.

In absolute determination Michèle was able to keep driving but only managed to persist for another five kilometres before being willing to admit it was futile, so she was forced to withdraw.

She had come so close to the championship win, only to have her hopes dashed at the very last.

At the end of the year’s competition Michèle Mouton won the International Rally Driver of the Year award at the Autosports Gala and a very happy Audi took away the coveted manufacturer’s world title.

Michèle Mouton with Fabrizia Pons had put in a heroic effort to achieve that result for Audi, the manufacturer had indeed become a household name.

Group B

1983 heralded the beginning of the powerful Group B cars, it is an era that that is famous or infamous depending on one’s perception. It was without doubt an era in which the power and handling of the cars tested the driver’s skills, discipline, wisdom and restraint like none before. Group B was to become the rally discipline that fired Michèle Mouton’s imagination.

Michèle and Fabrizia’s rally season opened in an Audi Quattro A1 which had a five cylinder turbocharged engine delivering 350 hp in a car that was both more powerful and more agile.

The first event was the Monte Carlo Rally, an event that proved unexpectedly disappointing as Michèle had to take evasive action to avoid a photographer, an action that resulted in her losing control and hitting a stone wall at around 100 km/hr. Happily neither Michèle nor Fabrizia, nor the lemming photographer were injured but the car was unsalvageable, as was Michèle’s competition.

For the Swedish rally the Mouton/Pons team finished in fourth place to the joy of Audi-Sports because they had a first, second, third and fourth place finish for their team. Champagne is such a nice way to celebrate success and no doubt the celebration was sweet.

In the Rally de Portugal Mouton/Pons obtained a second place. But it was in the Safari Rally in Kenya that Michèle proved her metal once again arriving at the finish line of that 1,600 km trial on three wheels, and obtaining a well earned third place in the process.

For the fast and challenging Tour de Corse Audi introduced a new version of the Quattro, the A2. This car was 70 kg lighter and the engine produced 30 hp more, making it faster, more lively, and more challenging to manage.

Making a competition engine produce more power can come with some downsides, the main being reliability. In the Tour de Corse Michèle’s Audi A2’s engine proved to be so “hotted up” that it caught fire. Then in the Acropolis Rally in Greece Michèle misjudged a hairpin and rolled, and then in the Rally New Zealand the A2’s engine failed on her.

In the Rally Argentina she finished in third place, but then in the 1000 Lakes Rally in Finland the A2’s hotted up engine caught fire again, but this time Michèle knew the trick to cool things down and she drove the car into a lake sufficiently to put the fire out.

Hannu Mikkola had advised her that this was a tried and proven technique that Finnish rally drivers used to put fires out – sort of like giving the car the Finnish sauna treatment – first the heat, then the ice water.

By this stage of Group B competition the cars of the Lancia team were proving to be a match for the Quattros and in the Rally Sanremo Michèle finished in seventh place.

Then at the end of the season in the RAC Rally in Britain Michèle finished in second place for each of the first twelve stages, only to have cold water poured over her success when a mechanic mistakenly poured water into the fuel tank of her car. Highly tuned rally cars do not respond well to being fueled with pure clean water and the result was much time lost for Michèle as repairs were done.

Despite the setbacks Michèle Mouton finished the year in fifth place in the 1983 Driver’s Championship.

1984 seems to mark the winding off period between Audi Sports and Michèle Mouton. Instead of driving she did commentating for the Monte Carlo Rally, but she then went on to a second place podium in the Swedish Rally, a result she was very happy about.

However Michèle was plagued by mechanical problems in subsequent competitions and some crashes, it would seem that the German engineers could not build a car tough enough to withstand the aggressive driving of this petit Frenchwoman.

Michèle had been nicknamed “Der Schwarze Vulkan”, which translates from German to English as “the black volcano, a reference to her jet black hair and fiery personality, both behind the wheel and in dealing with interviewers and others who managed to annoy her.

It was in 1984 that Michèle Mouton with teammate Fabrizia Pons made their debut at the Pikes Peak International Hillclimb in the United States. She finished first in class and second overall which was no doubt a satisfying result.

1985 saw Michèle and Fabrizia return to have another go at Pikes Peak and this time Michèle determined to win or crash trying, it was “der Schwarze Vulkan” at her best and she confessed after the drive that at one point she had really felt that she was going to crash, but she didn’t crash, and she won.

The course had been especially treacherous in the wake of a hailstorm but Michèle not only won but pruned thirteen seconds off American driver Bobby Unser’s 1982 record.

Bobby Unser turned out to be rather annoyed at the temerity of this Frenchwoman winning the event and breaking his record. In response “der Schwarze Vulkan” replied to him “If you have the balls you can try to race me back down as well”.

It was in late 1985 that Michèle Mouton broke off her contract with Audi Sports. It was time to move on and try something new, so she signed with French car maker Peugeot.

Fabrizia Pons had stepped down from rallying and was married, so Michèle managed to recruit Terry Harryman to be her co-driver.

The Mouton/Harryman team contested the German Rally Championships in a Peugeot 205 Turbo 16.

The Peugeot 205 Turbo 16 was a purpose built Group B rally competition weapon that had enabled Peugeot to win the world titles the previous year.

The standard Peugeot 205 was completely rebuilt by Heuliez who transformed it from a boringly front-engine front-wheel-drive ordinary car into a rear-mid-engine all-wheel-drive fire-breathing Group B road rocket.

It was a perfect fit for Michèle Mouton and she used it to best advantage.

The Mouton/Harryman team won six of the eight events in the German rally championship and Michèle Mouton became the first woman to win a major rally championship.

This was to be Michèle Mouton’s swansong.

The event that brought her to the decision to retire was the crash of Henri Toivonen and co-driver Bruno Saby whose car had gone off the road and burst into flames killing both.

The Group B cars had become a source of criticism because the sheer power and speed of them was said to be beyond the ability of a human driver to manage.

The critics of Group B have sometimes used video footage of lemming-like spectators in near misses with rally cars as part of their argument for the banning of Group B, although that spectator behavior was occurring before Group B was invented as we mentioned previously, even to the extent of spectators reaching out to touch cars as they sped past – sometimes leaving fingers in the car for the pit crews to discover later.

But the Toivonen/Saby crash was the event that brought about the end of Group B. When she heard about the crash Michèle Mouton had commented that “if they stop the Group B now, it will be the end for me.”

So it was that two weeks after winning the German Rally Championship Michèle Mouton would announce her retirement from rallying.

She had been privileged to be a part of an extraordinary era of motorsport and as that era drew to a close it was time for her to hang up her driving gloves, and so she did.

Life After Rallying

With the end of her driving career Michèle Mouton joined with sports journalist Claude Guarnieri and brought their daughter, Jessica, into the world in 1987.

Family proved to be all important, as it should be, but Michèle was still able to enjoy fast cars from time to time in the role of chase car driver, providing the technical support for competing teams, and as a press driver.

She also founded the international Race of Champions with Fredrik Johnsson. This event brings together champions from various motorsports such as rallying, Formula One, NASCAR and Le Mans to race each other in identical cars. This event has been created to honour the memory of Michèle’s friend Henri Toivonen.

Michèle Mouton was able to choose events she might come out of retirement and compete in from time to time. Such an event was the London to Sydney Marathon held in 2000. She and teammate Stig Blomqvist attained second place driving a Porsche 911.

Michèle Mouton became the first president of the FIA’s Women & Motor Sport Commission in 2010 with the aim of encouraging women to become involved in motorsport.

in 2011 she was appointed to be the FIA manager for the World Rally Championship, and also served on the nomination committee of the Rally Hall of Fame, although she had to recuse herself from that temporarily in 2012 when she herself was nominated and inducted.

Michèle Mouton honours her late father with her success. She said of him “He loved driving. He loved fast cars. And I think he would have loved to do what I did. He was a prisoner of war for five years and when he came back he never had the opportunity to compete. But he came to all the rallies I did. And my mother came, too.”

And of course he bought her first rally car and financed her first year in the sport that would become such a great part of her life.

Michèle Mouton was able to live her dream, in no small part thanks to the support of her parents, and to her own motivation and willingness to endure trials, and commitment to do her utmost.

Hers is a life that shines the way for any who would follow in her footsteps.

Picture Credits: Audi, Motosport Images, Renault, and others as individually acknowledged.

Jon Branch is the founder and senior editor of Revivaler and has written a significant number of articles for various publications including official Buying Guides for eBay, classic car articles for Hagerty, magazine articles for both the Australian Shooters Journal and the Australian Shooter, and he’s a long time contributor to Silodrome.

Jon has done radio, television, magazine and newspaper interviews on various issues, and has traveled extensively, having lived in Britain, Australia, China and Hong Kong. His travels have taken him to Indonesia, Israel, Italy, Japan and a number of other countries. He has studied the Japanese sword arts and has a long history of involvement in the shooting sports, which has included authoring submissions to government on various firearms related issues and assisting in the design and establishment of shooting ranges.