A Transatlantic Airliner for the Post-war World

The first wide-bodied airliner was not the Boeing 747, in fact it had a longer wingspan than a 747. It was an aircraft whose specifications were decided by a British government committee back in 1943 while the Second World War was still raging and victory was by no means certain. This airliner was the Bristol Brabazon, and the enduring legacy of its existence is the manufacturing facility built for it which is still in use to the present day.

To Moscow in a Liberator Bomber

Britain’s wartime Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, was a man confident that Britain would emerge from the Second World War victorious once the United States became involved. Churchill also wanted to get the Soviet Union on the Allied side and to this end he undertook the dangerous journey to Moscow via Cairo in Egypt to speak with Stalin in person. This journey was made in a Consolidated B-24 Liberator bomber which proved to be cold and uncomfortable and it was this experience that got Winston Churchill thinking that Britain had failed to build her expertise in creating transport aircraft, she had been so busy fighting a war.

Lord Brabazon and the Proof that Pigs Could Fly

Once back in Britain Churchill got started on the process of Britain preparing for her aviation requirements in a post-war world where she would need to be servicing her Empire, the Commonwealth, and her commercial aviation needs. Churchill approached the man he thought the obvious choice to lead a committee to decide on this aviation strategy, a man who had met the Wright brothers and had worked for Charles Rolls of Rolls-Royce fame, the first British person to fly back in 1908, and that man was John Moore-Brabazon, 1st Baron Brabazon of Tara. He was a Conservative politician and during the war was Minister of Transport and Minister of Aircraft production. Lord Brabazon also held the distinction of proving that pigs could fly by putting a small one in a wastepaper basket attached to the wing strut of his Short Biplane No. 2 aircraft on 4th November 1909 and taking it for a flight, pretty certainly earning himself a place in history as having done the first live cargo flight in an aeroplane.

Lord Brabazon’s committee first met on Christmas Eve of 1942, Lord Brabazon having been forced to resign his Ministry positions in 1942 when he expressed the hope that the Nazis and the Soviet Communists would destroy each other as they fought the Battle of Stalingrad: but he remained as chairman of the Brabazon Committee and by 9th February 1943 they had arrived at their recommendations for British civilian aircraft for the post-war era.

Type 1: A large long range aircraft for the Trans-Atlantic route.

Type 2: An economical aircraft like the Douglas DC-3 for European services.

Type 3: A four engine medium size aircraft for Empire routes.

Type 4: A jet propelled aircraft for Trans-Atlantic mail services.

Type 5: A twin engine fourteen seat regional airliner.

The task of creating the Type 1 large long range and luxurious Trans-Atlantic airliner was given to the Bristol company.

The Bristol Brabazon is Created

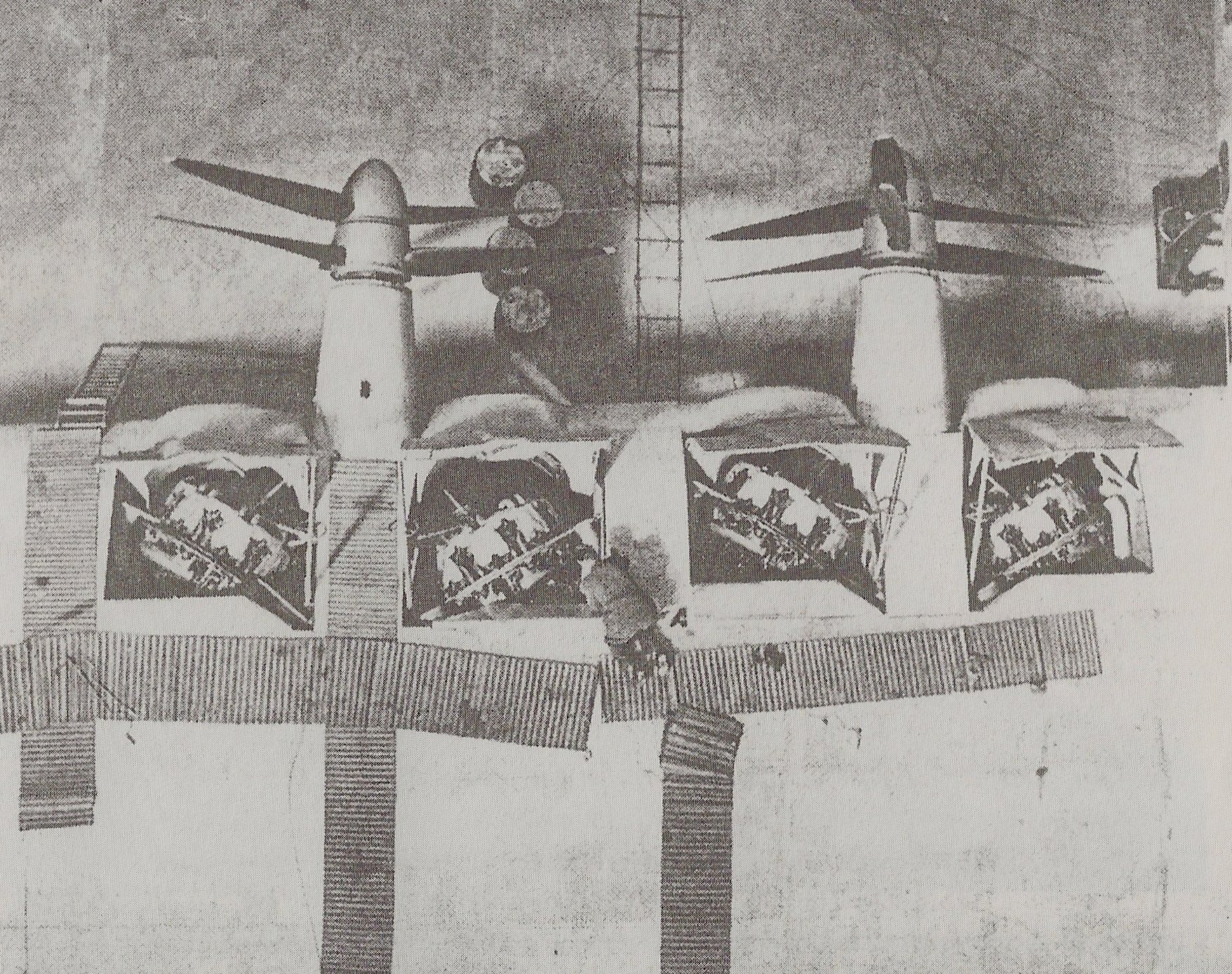

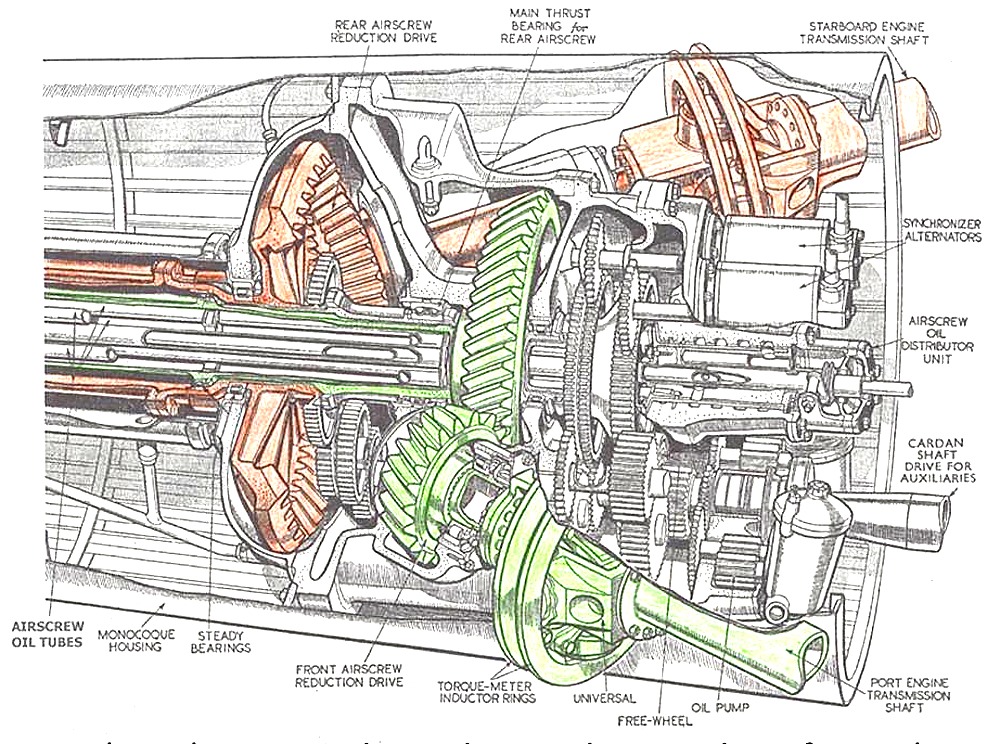

The company chosen to take on the contract to build the Type 1 Trans-Atlantic airliner was Bristol. Bristol had been working since 1937 on large bomber designs and one of these was in many respects similar to what would ultimately become the Brabazon. In 1942 the British Air Ministry had started looking for a heavy bomber capable of carrying a load of 15 tons of bombs and with a range of 5,000 miles (8,000 kilometers). The Bristol preliminary design had a wing span of 225 feet (69 meters) and was to be powered by no less than eight of the new 3,272 cu. in. (53.6 liters) 18 cylinder radial Bristol Centaurus engines which each produced 2,650hp. These engines would be arranged in pairs to drive four propellers in a pusher configuration.

Given the exigencies of the war it took Bristol until 1944 to create their initial design for the new Type 1 “Brabazon” airliner. This design was a little different to the bomber in that the engines were mounted angled in the wings to drive four sets of contra rotating propellers in conventional forward facing nacelles.

A Trans-Atlantic Palace of the Sky

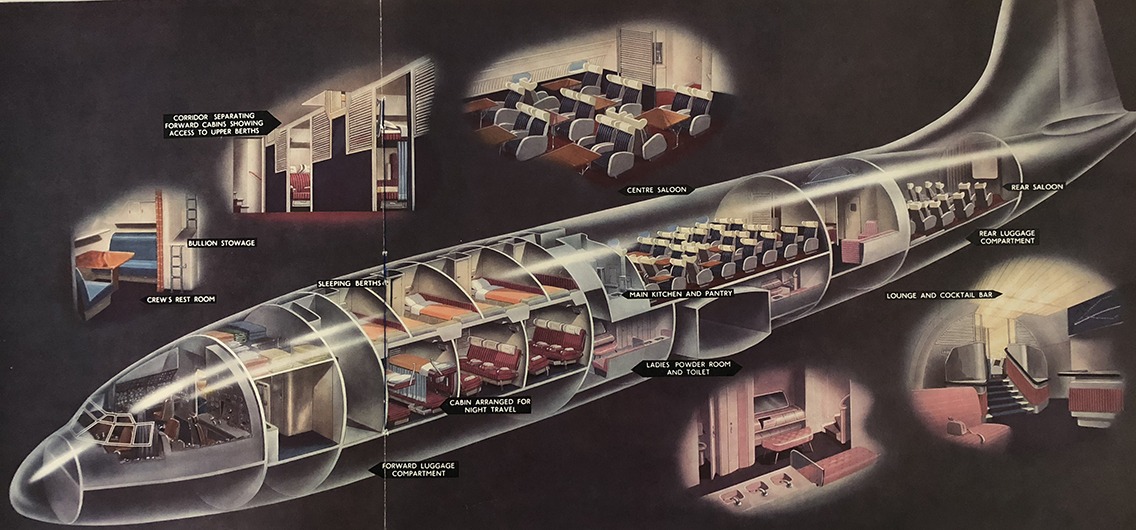

Although the original design parameters of this Bristol 167 aircraft could have been fitted out to carry 300 passengers the Brabazon report conceived of the plane being the epitome of luxury and only fitted out to carry 100 passengers. Each “economy” passenger was allocated 200 cubic feet of space (6 cubic meters: about the size of the interior of a medium car) and “first class” passengers were given 270 cubic feet (8 cubic meters). To accommodate this spaciousness the Bristol 167 Brabazon’s fuselage was 25 feet (8 meters) in diameter: which is about 5 feet (1.5 meters) more than the Boeing 747 which would come many years later. Not only was each passenger allocated rather extensive and luxurious space but the aircraft was also equipped with a cocktail bar, and a movie theater in the rear. In a sense it was fitted out to compete with the luxury ocean liners that carried passengers between London and New York and this was not such a silly idea. Back then travel by ship was the norm, travel by air was a new thing that had to establish itself as a better and more comfortable way of traveling.

The downside of providing this level of luxury was of course that if an aircraft capable of carrying 300 passengers was set up to only carry 100 then the price of the ticket to fly would be three times higher, thus making travel on the new Bristol 167 “Brabazon” only affordable by the rich. The people at Bristol, and Lord Brabazon’s committee seem to have believed that this was perfectly sensible as they thought air travel was something only the rich would be able to afford. The notion of inexpensive air travel for the lower income masses does not seem to have entered their thinking. Such people would of course continue to travel by ship.

In order to make this very large aircraft as light as possible Bristol used custom thicknesses of aluminum sheeting to exactly meet the structural requirements of each section: this trimmed tons off of the aircraft’s final weight. The technology extended to every detail down to the rivets, which were sealed in place with aircraft dope to reduce the required number.

The Shed’s Too Small and the Runway’s Too Short

One of the obvious things that would have to be built was a bigger shed that this “jumbo” of an aircraft could be fully assembled in. Bristol undertook the task of purpose building a new shed in October 1945 and while this was underway the work on a full scale mock-up was undertaken in the company’s existing No. 2 Flight Shed, and construction of the first Brabazon prototype in Bristol’s existing hangar. Once the new hangar was constructed the delicate job of transferring the partly built Brabazon into it was done. It was a job that required careful maneuvering as there were literally inches to spare in getting the partially constructed plane out of the existing hangar. The new hangar purpose built to provide a production line for Brabazons is still in use today for the building of other aircraft.

Not only was the hangar too small but the runway at the Bristol Filton Airport was deemed too short for the new aircraft. This was not because it was thought the Brabazon would need a much longer runway, but it was to allow for safe recovery should an engine fail at the moment of take-off forcing the take-off to be aborted. It was reasoned that the runway needed to be 8,000 feet long to allow for such an emergency and so this was done. The runway extension forced the demolition of the village of Charlton whose residents were reluctantly moved to the town of Patchway.

“Good God it Works”

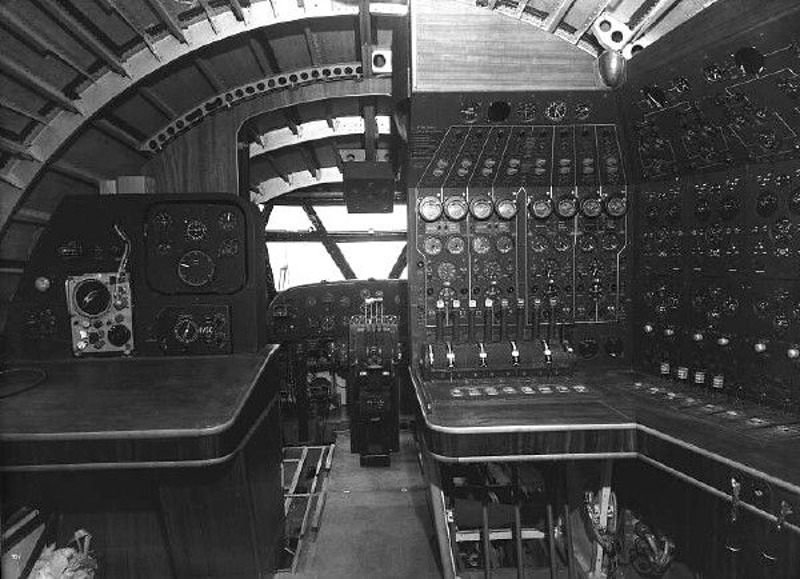

Once the Bristol 167 Brabazon prototype was completed and all the on-ground testing had been done it was time for this very big bird to take to the skies. This aircraft featured a number of “firsts” and among them was that it was fitted with fully powered flight controls. It was the first aircraft to be fitted with fully high pressure hydraulics, and the first to have electric engine controls. The aircraft was also fitted with a gust elimination system designed to prevent bending of the wing surfaces caused by turbulence: if you’ve been on a modern passenger airliner in heavy turbulence and watched as the wings flap up and down violently you will have a picture of what “bending of wing surfaces” looks like. The gust elimination system consisted of a sensor controlling device mounted in the aircraft’s nose which operated servos which applied straightening pressure on the wings to respond to the bending forces. This was necessitated because of the structural methods used to lighten the aircraft.

The Bristol 167 Brabazon required a crew that included pilot, co-pilot, flight engineer and navigator. The pilot for the testing was Arthur “Bill” Pegg, who had spent some time in Fort Worth, Texas at the invitation of American aircraft maker Convair flying their large B-36 Peacemaker strategic bomber.

Initial ground testing was first carried out on 3rd September 1949 and it showed that the front nose-wheel steering did not work properly so it was temporarily disabled. With that done it was time for the big bird to take her first flight and this took place on the following day with an audience of around 10,000 members of the press and public: so if this was going to fail it was going to be a spectacularly public failure.

The Brabazon headed down the runway, lifted up her non-steering nose-wheel, and then gracefully ascended into the sky with Bill Pegg exclaiming over the radio “Good God it works”. And work it did, it was pleasantly easy to fly and testimony to the work of the “boffins” who had got all their sums right and made a quite fabulous aircraft.

The “Queen of the Skies” is Rejected

The Bristol 167 Brabazon was capable of a cruise speed of 260 mph (420 km/hr) and a top speed of 300 mph. Its cruise speed was limited by the Bristol Centaurus radial piston engines and it was decided that a Mark 2 Brabazon was needed with technical improvements including a switch to Bristol Proteus turboprop engines. This would enable an increase of the aircraft’s cruise speed to 330 mph (530 km/hr). Not only would the turboprop engines increase the aircraft’s cruise speed but they would also increase its ceiling and decrease its weight by 10,000lb. Turboprop engines were and are very fuel efficient so there were also improvements to the aircraft’s operating costs. The construction of the Mark 2 was hampered however by technical problems encountered with the turboprop Proteus engines and solutions to those problems were found too late to save the Brabazon.

In 1949 rival aircraft maker de Havilland debuted their jet powered Comet which being jet powered was attractive to airline customers. In 1951 American company Lockheed debuted their Super Constellation which could also carry a hundred passengers at 330 mph and being a smaller aircraft it could do it rather more inexpensively. Thus it was that the Bristol 167 Brabazon was faced with capable and more affordable competition with the result that it totally failed to obtain any orders from a commercial airline, or from the British Air Force. The writing was on the wall but Bristol continued to demonstrate the Brabazon up until October 1953 when the “Queen of the Skies” was sold for scrap along with the partially completed Mark 2: leaving as their legacy a wealth of technical advances and the 7½ acre 1,052 feet long, 410 feet wide, and 117 feet high hangar built for it which is a major facility in use to the present day.

When the British fail they tend to do it magnificently: and the Bristol 167 Brabazon turned out to be a magnificent failure. She was a superbly engineered aircraft built on the orders of a government committee instead of being built to the requirements of commercial airlines. Had it been offered with a seating capacity of 300 it might have managed to sell, but it was aimed at providing luxurious travel for wealthy people.

Interestingly Britain would repeat this mistake again when it created another aircraft aimed at wealthy travelers, and that aircraft was the supersonic Concord.

There is an excellent documentary about the Bristol Brabazon which we include here courtesy ricardoroberto100 on YouTube

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qxhbMZbh_O0″ /]

Photo Credits: Bristol Aeroplane Company (except where otherwise marked).

Jon Branch is the founder and senior editor of Revivaler and has written a significant number of articles for various publications including official Buying Guides for eBay, classic car articles for Hagerty, magazine articles for both the Australian Shooters Journal and the Australian Shooter, and he’s a long time contributor to Silodrome.

Jon has done radio, television, magazine and newspaper interviews on various issues, and has traveled extensively, having lived in Britain, Australia, China and Hong Kong. His travels have taken him to Indonesia, Israel, Italy, Japan and a number of other countries. He has studied the Japanese sword arts and has a long history of involvement in the shooting sports, which has included authoring submissions to government on various firearms related issues and assisting in the design and establishment of shooting ranges.