The Ultimate Citroën “Grandes Routières“

One of the greatest, if not the greatest of the post-war French luxury performance cars was the Facel Vega. It was a car that became legendary racing driver Sir Stirling Moss’s favorite and for good reason. It provided a combination of V8 performance with decent handling and an interior decor that has aguably never been matched: it was so gorgeous that Ringo Starr of the Beatles bought one. But Facel Vega went out of business in 1964 leaving a gaping void that the management at Citroën believed they could fill. So it was that the vision for the Citroën SM was born as “Projet S” and it would result in a car that would be so good in a point to point role that not many people seemed to truly understand just how far ahead it was. In fact it was so far ahead that there were even those who were afraid to try driving it.

It might have been among the first production cars in the world to be fitted with a Wankel rotary engine, but Citroën did not manage that. It might have been fitted with a six cylinder engine that Citroën had begun developing themselves, but that did not eventuate either, and “Project S” would become the Citroën SM fitted with a Maserati designed V6 which, believe it or not, was one of very few conventional things about the car.

Citroën in the “Race for Space” Era

Once the Second World War was over the “Race for Space” got started and the media and industry got very excited about new technology, “space age” technology. The car industry got into this with considerable enthusiasm such that we saw staid and conservative British prestige car maker Rover embark on a gas turbine powered car program as did Ford and Chrysler in the United States.

Other than the efforts at creating jet powered cars the other engine technology that was new and looked promising as a “space age” engine for automobiles was the Wankel rotary engine. So while the British and Americans were busy trying out gas turbines the French and Japanese signed licensing agreements to develop the Wankel rotary engine, which promised to be ultra quiet, smooth, and able to rev up to stratospheric heights.

French car maker Citroën got into a partnership with German company NSU in the Comotor project to iron the bugs out of Felix Wankel’s prototype while fledgling Japanese car maker Mazda decided to go it alone. The end result was that Citroën and NSU failed to fully solve the problems with the Wankel design although NSU put a car into production in 1967, the Ro 80, which proved to be a flop. Mazda on the other hand did manage to debug the Wankel and started out fitting their engine in the Mazda Cosmo sports car also in 1967 and a whole range of road cars after that.

So it was that the powerful triple rotor Wankel engine that Citroën could have used for its flagship Grand Touring car of the 1970’s did not materialize and they found they needed an alternative.

The Citroën DS Gives Birth to the Citroën SM:

In understanding the development of the Citroën SM we need to look back at the car that fathered it: the Citroën DS.

Citroën had started work on their vision for a car for the future in 1937-1938 before the nasty Nazis invaded France and made a nuisance of themselves until the solution to the National Socialist problem was accomplished in 1945. Once the scourge of National Socialism was dealt with the designers and engineers at Citroën got back to creating the car they’d started work on in the 1930’s.

French engineers have acquired a reputation for thinking in depth about the function they want, then they create the engineering solutions and finally clothe the thing with beautiful aesthetics. French steam locomotive designer André Chapelon is an example of this and his railroad locomotives were things of supreme efficiency and beauty. The engineers at Citroën were just like this and at the Paris Motor Show of 1955 they unveiled what must be regarded as the most imaginative automobile the world had ever seen: the Citroën DS.

The about the only conventional thing about the Citroën DS was its OHV pushrod engine. In creating the DS the engineers had considered what a driver really needed a car to do. Most drivers are not using their car for motor racing or rallying and have no interest in doing so. What they need is a car that is easy to drive, safe, easy to change a flat tire, a car that would be stable on a paved road and at motorway speeds, yet a car that could negotiate a rough track while giving its occupants a comfortable jolt free ride and having enough ground clearance to avoid rock damage to the car’s underside. How to accomplish such a thing?

In order to have a car that would be stable and comfortable at motorway speeds normally required a relatively low ground clearance: but for rough roading or off-roading a high ground clearance and lots of suspension travel were needed. Paul Magès was charged with creating a suspension system that would accomplish both and his solution was the Citroën hydro-pneumatic suspension system which used air pressure and hydraulics to provide a suspension system that was adjustable for height from the driver’s seat, independent, and self-leveling even under braking in which it would not allow the car to pitch forward out of balance but would cause the car to squat down evenly maintaining balance. Added to that this hydro-pneumatic suspension allowed the car to be selectively jacked up from the driver’s seat making changing a flat tire a relatively easy task. It was simply brilliant.

The Citroën DS was clothed in an aerodynamic body whose aesthetics were “love it or hate it”, but brilliantly French. It was the work of Flaminio Bertoni and French aeronautical engineer André Lefèbvre and it was so different to anything else on the road it was unmistakable.

The Citroën DS made its debut at the Paris Motor Show of 1955 and went on to make its mark on the world remaining in production until 1975, which was also the year its luxury sibling the Citroën SM would also cease production.

A Citroën-Maserati

With the Citroën DS and its cheap cousin the ID both such a great success that they had become icons of France, Citroën began thinking about creating a luxury coupé to fill the void left by the ending of Facel Vega: a car that would have all the advantages of the DS but with a vastly superior engine and prestige coachwork. This car was to be based on the DS yet have a unique design of its own. It was to be capable of high speed motorway cruising yet able to cope with rough roads and tracks like no Ferrari or Porsche could. It was to be not a race or rally car, but the most accomplished point to point car ever created.

When the effort to develop the Wankel engine proved so costly that it almost bankrupted them Citroën needed to have a re-think about where they could get a suitable conventional but prestigious high tech engine for their planned Grand Touring car. The solution to that problem came in a move that has puzzled many: Italian exotic car maker Maserati was up for sale so management at Citroën decided to buy it in 1968 and put a Maserati engine into their new halo car instead of the hoped for Wankel.

Almost immediately after the 1968 purchase of Maserati Citroën instructed Giulio Alfieri, Maserati’s Chief Engineer, to create a V6 engine of 2.7 liters capacity to power their new grand touring car. The engine capacity being required because of France’s vehicle licensing regulations which provided much less expensive tax for vehicles under 2.7 liters capacity. This was no doubt one of the reasons the company had invested so heavily in the Wankel engine whose capacity is always very low by comparison with the power it produces.

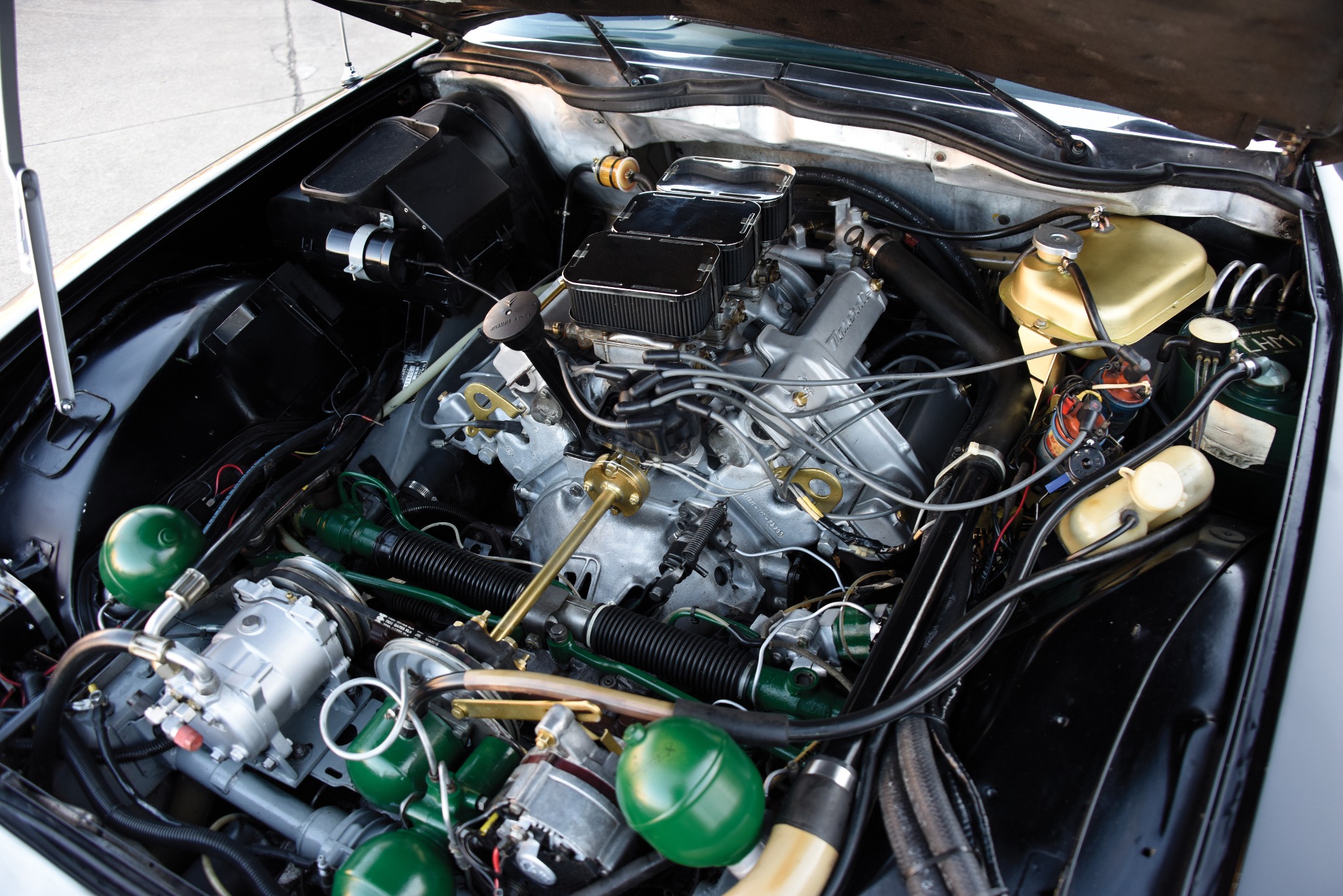

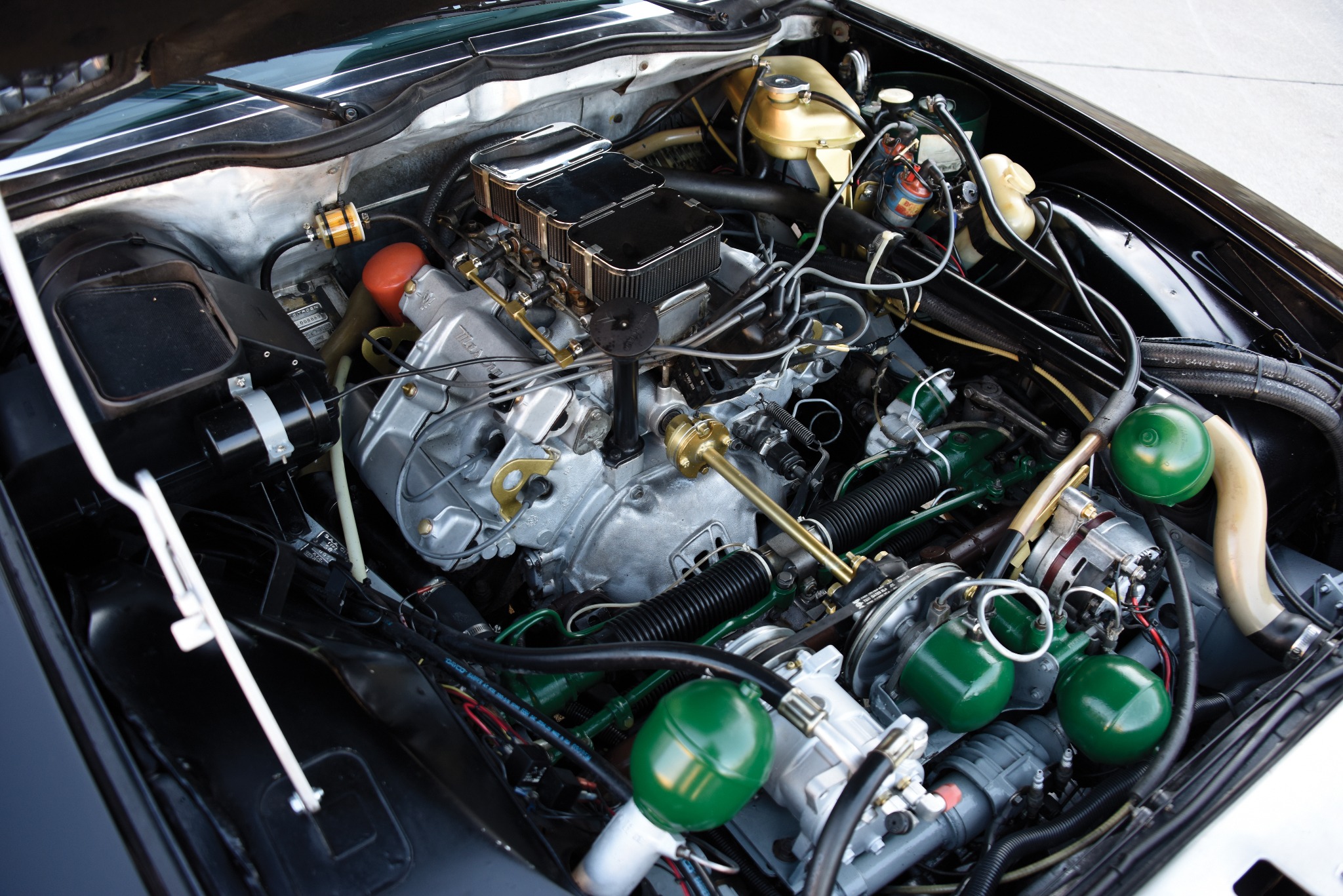

Alfieri was given a six month time frame in which to create the new engine: he accomplished that task in three short weeks. The task was done by taking the existing Maserati Indy V8, cutting off two cylinders, and shortening the stroke from 85 mm to 75 mm. This brought the original V8’s capacity of 4,136 cc down to a neatly French tax friendly 2,670 cc. By the time the new all alloy DOHC V6 was fully developed it had been completely re-engineered and was capable of delivering up to 200 bhp depending on how it was configured. As set up for regular production the engine was fitted with three Weber 42DCNF2 carburetors and produced 168 hp.

Over the years of production this engine would be made in three variants. From 1970-1972 the Citroën SM 2.7 was installed with the 2,670 cc Type SB engine which was fitted with 3 Weber 42DCNF carburetors mated to a five speed manual transaxle. This engine produced 168 hp (170PS) giving the car a top speed of 220 km/h (137 mph), (Interestingly that same five speed Citroën transaxle would be chosen by Lotus to fit to their Esprit sports car). For 1973 this same engine was offered with a three speed automatic transmission in the Citroën SM 2.7 Automatique which had a top speed of 205 km/h (127 mph). From 1972-1975 a Type SC fuel injected engine was offered with the five speed manual transaxle. This was the Citroën SM Injection and its Maserati V6 was fitted with Bosch D-Jetronic fuel injection giving the engine a power output of 176 hp (178 PS) to provide a top speed of 228 km/h (142 mph).

In 1973 a larger capacity Type SD 2,965 cc engine was offered in the Citroën SM 3.0. The Type SD engine breathed through the 3 Weber 42DCNF carburetors as used on the smaller capacity engine and produced 178 hp (180 PS). The 3.0 liter engine was offered as the Citroën SM 3.0 with a five speed manual transaxle and top speed of 225 km/h (140 mph), or as the Citroën SM 3.0 Automatique with a three speed automatic and top speed of 205 km/h (127 mph).

The advanced technology did not stop at the Maserati engine. The new car was designated the Citroën SM (probably in reference to its original designation as Project S for “Sports”, and “M” for Maserati). The car was equipped with the André Lefèbvre designed hydropneumatic suspension integrated with the braking system, the brakes being discs front and rear with the front discs mounted inboard to reduce unsprung weight. The brake pedal was an odd looking mushroom shaped rubber ball on the floor which actuated the hydraulic system.

The steering system of the Citroën SM was way ahead of its time. It was called the Citroën DIRAVI (i.e. DIrection à RAppel asserVI). This steering system was speed sensitive. This means that if the car was traveling slowly such as when doing a parking maneuver the power steering would make turning the wheel light and easy, but if the car was on the open road doing higher speeds the steering would become heavier so as to impart the right amount of feel to the driver. This system provided two turns lock-to-lock to provide go-kart like steering that adjusted itself to driving conditions. The DIRAVI system also incorporated hydraulically actuated self-centering so if the driver took his/her hands off the wheel it would rapidly self-center. This steering setup was perfect for those trained in the British Police “Push-Pull” steering technique as taught at the Hendon driving school.

The styling of the car was done by Citroën’s head of styling Robert Opron and, just like the DS series before it the car’s looks were a love it or hate it proposition. The look had just a hint of the DS about it with no less than six Cibié halogen headlights with integrated covers to assist with the car’s aerodynamics. The inner pair of headlights were connected to the steering so they would always look in the direction the car was turning: something that is of great value when negotiating tight hairpins at night.

The cars made for the US market were not fitted with the steering connected headlights as these contravened US regulations. So US market cars only had four headlights which were fixed to look straight ahead in the conventional way.

The production car’s aerodynamic coefficient was 0.34 and there are not many production cars past or present that better that.

A “Grandes Routières” par Excellence

Being dramatically technologically advanced has its advantages and disadvantages. The Citroën SM provided a driving experience that required work in order for the driver to become accomplished with it. The behavior of the steering and brakes was quite unlike other cars on the road. It was a car that some people invested the effort into learning, and that effort paid off, while there were others who didn’t want to go through that sort of effort.

In terms of performance the Citroën SM did standing to 60 mph in 8.5 seconds and had a top speed of 137 mph, which puts it squarely in the same league as the Jensen Interceptor. But this was a car that provided comfort and stability at speed on the tarmac and on rough roads alike. The DIRAVI steering system worked to prevent potholes and rough surfaces from upsetting the steering direction or cause feedback through the steering wheel. It was reported by Popular Science magazine that the SM had the shortest stopping distance of any car they had tested.

The degree of technological sophistication inevitably led to problems in maintaining these cars properly. The Hydro-pneumatic suspension system could only be competently maintained by Citroën workshops which were widespread in France and much harder to find elsewhere. The Maserati engine however also required specialist knowledge to maintain it properly also. This included tuning and working with the triple Weber carburetors but also required manual adjustment of the timing chain setup of this interference engine design. If that was not properly looked after then engine life could be as short as 60,000 km, and would be expensive to overhaul.

The word about the car’s maintenance needs progressively got out and sales of the Citroën SM declined. In that period, 1974, Citroën finally went bankrupt, a process in part caused by the resources they’d invested into the development of the Wankel engine, to no avail. Peugeot obtained ownership of Citroën in May 1975 and promptly sold Maserati, and ended production of the Citroën SM.

In total 12,920 Citroën SM were made of which just 2,400 were exported to the North American market.

One of those North American market cars is coming up for sale by RM Sotheby’s at their Palm Beach auction which will be held over March 20-21, 2020.

You will find the sale page for that car, which is the black car featured in our pictures, if you click here.

The sale car is a 1973 model fitted with the 3.0 liter engine and five speed manual transmission. It also features air-conditioning and power windows in addition to the SM’s standard power brakes and DIRAVI steering system.

The Citroën SM was a car that was ahead of its time, it had enormous potential but arguably the dealer network was perhaps not completely able to provide the timely maintenance essential to keep it working as it was created to be. It remains however an outstanding point to point luxury high performance car that provides excellence in comfort and safety almost regardless of the road or dirt track it is asked to negotiate.

Photo Credits: All pictures of the black 1973 Citroën SM 3.0 North American Market car courtesy Thatcher Keast @ RM Auctions. All other pictures courtesy Citroën.

Jon Branch is the founder and senior editor of Revivaler and has written a significant number of articles for various publications including official Buying Guides for eBay, classic car articles for Hagerty, magazine articles for both the Australian Shooters Journal and the Australian Shooter, and he’s a long time contributor to Silodrome.

Jon has done radio, television, magazine and newspaper interviews on various issues, and has traveled extensively, having lived in Britain, Australia, China and Hong Kong. His travels have taken him to Indonesia, Israel, Italy, Japan and a number of other countries. He has studied the Japanese sword arts and has a long history of involvement in the shooting sports, which has included authoring submissions to government on various firearms related issues and assisting in the design and establishment of shooting ranges.