Background: A Nation in Recovery

In the wake of the Second World War, following on as it did from the Great Depression and the First World War, ordinary people were still trying to build a new life for themselves and the industries shattered by war were trying to rebuild for a new era, an era people hoped would be filled with hope. Even into the early 1950’s Britain was still in the throes of austerity and wartime rationing remained because of the lack of supply. Germany was in much the same condition, and her industries were working to reinvent themselves to survive, and hopefully prosper, in the brave new post war world. Auto maker BMW survived by building bubble cars as did aircraft builders Messerschmidt and Heinkel, but Mercedes forged ahead with building conventional cars and, amazingly, were quick to embark on a motor sport program, in all likelihood in order not only to build up their own reputation, but also to rebuild the nation’s shattered pride.

Mercedes Reenters Motor Sport

In the aftermath of the two world wars, with the Great Depression as the meat in the sandwich in between them, Mercedes were in a position of having limited capital, and limited access to raw materials. The cars they were making were models from the prewar era and it was far too soon for them to invest resources into creating new technology. Thus it was that to reenter motorsport Mercedes looked at their existing technology inventory, and also looked at the emerging postwar motorsport scene, and made decisions as to the most wise way they could use motorsport to rebuild the company’s positive image.

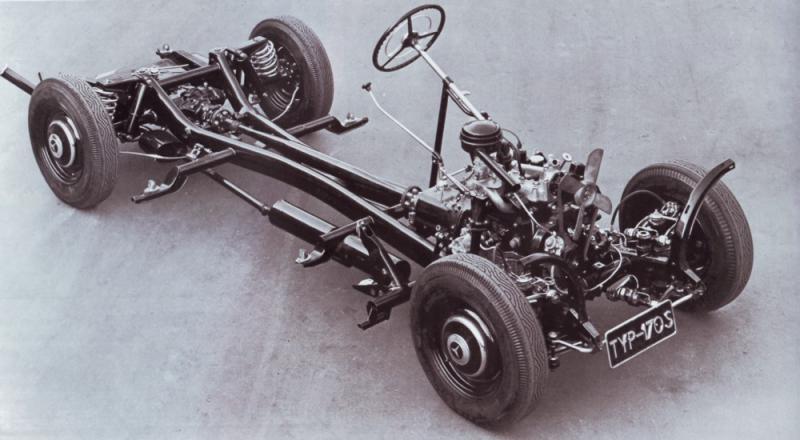

Mercedes first postwar production automobile was the prewar designed 170V and this was also the model used for their first postwar effort at motorsport, the 1950 6 hour ADAC race held at Nürburgring. The 170V managed seventh place in the up to 2,000cc class but managed the distinction of posting the fastest lap time for a touring car in the race.

Following this the decision was made to build a sports car that could have an excellent chance at winning such major endurance events as the 24 Hours Le Mans which had resumed in 1949.

The W194 Endurance Racing Car

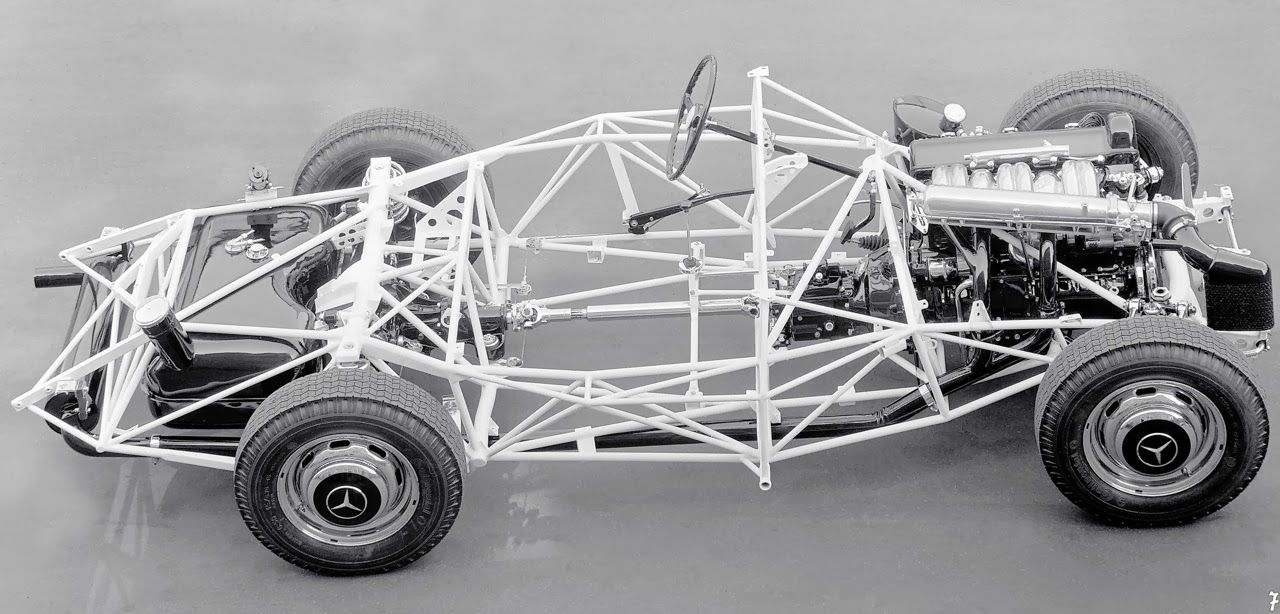

For the technological base for their new sports racing car Mercedes-Benz engineers did not look to the 170V however but to the much bigger luxury Mercedes-Benz 300 (W184) limousine, which would come to be known as the “Adenauer” because of its use by Germany’s post war Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany, Konrad Adenauer. The new sports car was not built on the heavy conventional chassis of the W184 however but instead a lightweight aluminum tubular spaceframe was created complete with independent suspension front and rear. The spaceframe chassis weighed a scant 140-150lb.

The 300SL (“SL” = “Super Leicht” i.e. “Super Light”) used the base engine of the W184, which was the SOHC 3.0 liter (2,996cc/182.8 cu. in.) in-line six cylinder, but in a modified M194 version equipped with triple Solex carburetors. The M194 engine was tilted 50° to the left to enable it to fit under the low hood of the new W194 sports car while the cylinder head was angled back the other way to enable the use of larger valves. The engine featured a dry sump to provide reliable oil feed during the forces of extreme cornering and braking under racing conditions. The tuned and developed M194 engine initially produced 228 hp and this was raised to 240 hp as development work progressed. The car used not only the base engine of the W186 luxury car but also its transmission (gearbox and final drive).

The 300SL was campaigned in 1952 with great success, taking second place in the Mille Miglia, first second and third in the Bern Sports Car Prize, first and second at Le Mans while also setting a new average speed record, and the 300SL also made its way across the Atlantic to Mexico to compete in the Carrera Panamericana. That car, driven by Karl Kling and Hans Klenk, achieved a first place victory also, a feat made all the more remarkable because at one point they’d had an overly friendly buzzard come through the windscreen to pay them a visit. Suffice to say the buzzard did not remember much about its through the glass adventure while Kling and Klenk no doubt had the experience etched in their minds as a story to tell for years to come. Klenk was the one who finished up scratched and bloodied by his close encounter of the buzzard kind. After this incident the car was fitted with protective bars on the windscreen to keep feathered friends out of the cockpit.

This video of the highlights of the event is courtesy Mercedes-Benz

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=isw9fKWFYMM” /]

The Creation of a Production Version of the 300SL

When it was originally created the 300SL had only been intended as a competition car. However, the car’s successes in competition led US Mercedes-Benz Director Max Hoffman to see the sales potential for a limited production 300SL on the American sports car market. So he suggested this to Mercedes in Germany at a director’s meeting in 1953. Hoffman put in an order for 1,000 such cars and this was approved by Mercedes General Director Fritz Konecke. For their racing car to be wanted as a road going model looked to be exactly the sort of result that Mercedes-Benz had been hoping for. The pure-bred racing car would need some changes and refinements, but it had the potential to positively affect Mercedes-Benz sales across the board.

The 300SL road car was based on a spaceframe chassis just like the competition car. Instead of aluminum the road car’s spaceframe was made of chrome-molybdenum steel. Similarly the road car’s body was made of steel, but with the hood/bonnet, door skins, boot/trunk lid and dashboard being made of aluminum. It was possible to order the 300SL with an all aluminum body but at significant additional cost: one source estimates the additional cost at around DM5,000, and thus only twenty-nine were made so equipped.

Because of the design of the lightweight spaceframe chassis high side sills were necessary to provide the structural stiffness needed. This in turn required that the iconic gull-wing doors would be required, and it meant that wind-up windows would be impossible.

The high side sills gave the driver and passenger a feeling that the car wrapped itself around them adding to its sports car feel, but getting in and out posed something of a challenge. To make getting into and out of the car easier the steering wheel was made to tilt under and away from the driver, much like the steering wheel on a British Daimler Ferret Scout Car.

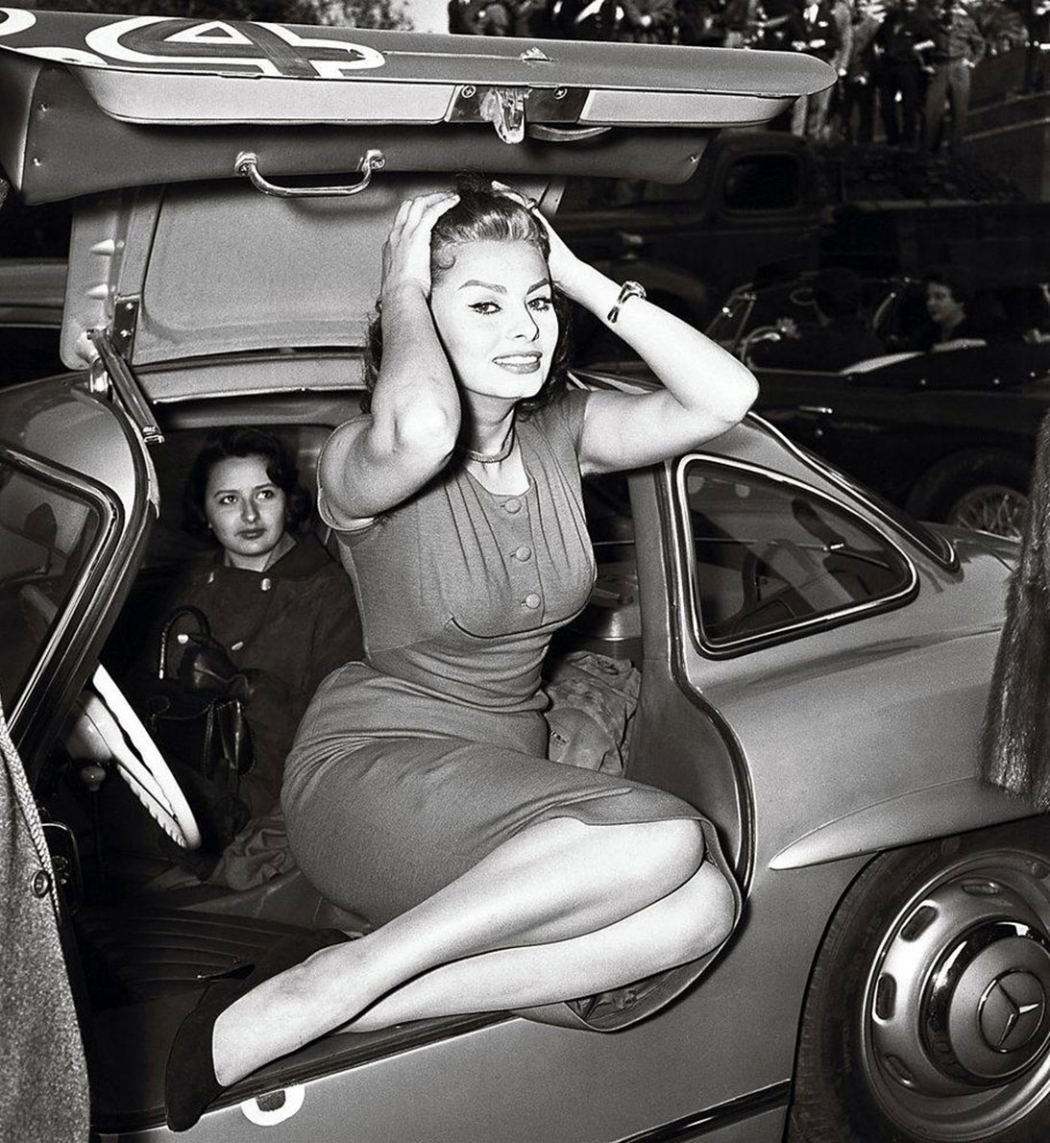

Entering the 300SL was still a process that required the driver and passenger to learn a specific technique. To get in the gullwing door is opened and then the driver sits on the sill, angles their legs around and into the car, then uses their hands, one on the sill and the other on the seat, to lift their body and lower themselves into the seat. Getting out is the opposite operation. This was probably a quite sporting sort of expectation for a 1950’s man but interestingly the 300SL was purchased by women also, among the most famous being Italian actress Sophia Loren, who was able to make her entries and exits from the car in an appropriately ladylike fashion.

Fitted into the spaceframe chassis of the 300SL was an engine updated from the SOHC M194 fitted into the 300SL racing car. This new M198 engine was, just like the racing car engine, slanted to the left by 50° with the cylinder head angled to the right enabling the use of larger valves and also to keep it more accessible for maintenance. The 300SL Coupé engine retained the dry sump lubrication system, necessary to ensure the height of the engine would fit the low space under the hood/bonnet and also providing the advantage of reliable oil feeding under extremes of cornering and braking. The significant difference between the two engines was the change from the triple carburetor fuel system of the racing M194 engine to a Bosch mechanical direct fuel injection system for the M198 of the 300SL Coupé road car.

The M198 fuel injected engine produced 220 hp @ 5,800rpm and torque of 206 lb/ft @ 4,900 rpm. The SOHC engine was equipped with a duplex timing chain and had a compression ratio of 8.55:1. The factory offered an optional Sports Cam version of this engine which boosted power to 240 hp at no charge.

The intention of using the Bosch mechanical fuel injection system was to keep the car’s power levels up close to the competition car’s, but to keep it flexible and make the car easy to drive for non-competition drivers, especially in traffic and the usual driving situations a road car will encounter. The singular disadvantage of the mechanical fuel injection system was that when the engine was switched off, as it was in the process of stopping, the mechanical fuel injection would continue to inject fuel into the cylinders with the potential for fuel to then run down into the sump progressively causing the oil to be thinned by the fuel. The solution was more frequent oil changes, with factory recommendation being every 1,000 miles/1,600 km.

The M198 fuel injected engine was fitted with a large oil cooler, much like its racing sibling. An oil cooler that will serve to keep the engine oil at a good temperature when racing across the desert of Mexico would, predictably, cause oil over-cooling in mild or cold weather conditions so sensible owners would either fully or partially block off the air flow to the oil cooler to ensure the oil temperature was kept at an optimal level. The engine’s oil capacity was a large 15 liters (4 US gallons) further exacerbating the need to be conscious of oil temperature because of the difficulty of getting that quantity of oil up to a healthy temperature level.

The car having been originally designed as a long distance endurance racer the fuel tank capacity was a generous 130 liters (34.3 US gallons). With fuel consumption of the order of 17 liters per 100 km (14 miles to the US gallon) the 300SL had a range of around 700-800 km depending on driving conditions, rather less than that in racing conditions. The large fuel capacity came at a price of course, that being at the expense of boot capacity. With a spare tire in the boot/trunk there is not a lot of additional space for luggage.

The transmission used in the 300SL coupé was the one used in the Mercedes 300 “Adenauer” limousine. This comprised a single plate clutch and four speed synchromesh gearbox with a rear mounted ZF limited slip differential that used swing axles to provide for independent rear suspension. The 300SL Coupé was offered with a range of final drive ratios; 3.64:1 became the most common default choice, but the others available were 4.11:1 (best for hillclimb events), 3.89:1, 3.42:1, and 3.25:1 (which provided the highest possible top speed of 161.5 mph).

Having its origins in a racing car the clutch pedal in early versions of the 300SL Coupé was quite heavy. In order to ensure the car was attractive to the widest range of potential customers this was remedied by fitting a better clutch arm helper spring to significantly reduce the effort required to use it.

The racing heritage of the 300SL is apparent in its suspension and brakes, although it is important to remember that this was a 1950’s design and that disc brakes were a very new thing. Front suspension of the 300SL coupé was by double wishbones with coil springs and a stabilizer bar. Rear suspension by radius arms and coil springs with high pivot swing axles. Brakes 260mm (10.2″) power assisted drums front and rear.

The 300SL was fitted with recirculating ball steering. Tires were 6.50×16.

The 300SL Coupé Morphs from Racing Car to Luxury Grand Touring Car

The production 300SL Coupé provided an attractive level of luxuriousness by 1950’s standards. The build quality was second to none and that of itself instantly gives a car the look and feel of being a cut above the ordinary. Mercedes cars were not normally ostentatious but were of high quality in all aspects; fit, finish, quality of materials, mechanical excellence.

Most of the original 300SL Coupés were painted in metallic gray but other colors were available to order. Given the car’s limited boot/trunk space it was common practice to provide fitted luggage that would fit securely behind the driver and passenger seats, extending the luggage capacity of the car significantly.

On the road the 300SL offered controllable power, speed and comfort in a relatively quiet car. Steering and handling were predictable and precise although the driver needed to be aware of the potential for getting into trouble caused by the swing axle rear suspension. This meant that the driver needed to understand that firm braking whilst in a corner was to be avoided. Hard braking in a corner in any car regardless of suspension is generally to be avoided because it transfers the car’s weight to the front outside wheel, and in extreme cases can cause that tire to fail often causing the car to gracefully lift up diagonally vertically in the air as it rolls and comes down hard on its roof. If the car is fitted with swing axles this effect comes into play quickly and with little warning. Any car with swing axles, such as the original Volkswagen, and many older Mercedes models including the 300SL will produce this effect.

In production from 1954-1957 the 300SL Coupé underwent a modest number of improvements. The heavy clutch pedal pressure was ameliorated by a redesigned system, the early cars were fitted with a long gear lever that worked directly into the top of the gearbox, a bit like the old Austin-Healeys, but this was changed to a standard gear lever with a linkage system to the gearbox. Although the car was offered with a range of final drive ratios experience settled on the 3.64:1 as standard.

Conclusion

The Mercedes-Benz 300SL Coupé is one of the great cars of the twentieth century. It made its debut at a time in history when people were looking for things that gave them hope that despite the wars and Depression that life was going to get a great deal better, and that the ugliness of the previous decades was past. The 300SL Coupé was a car that not only gave Mercedes a dose of hope and prestige, but it also served that purpose for the German people.

1,400 300SL Coupés were made, the majority of which were exported to the United States. It was a car that was owned by some of the most famous movies stars of the 1950’s, including Clark Gable, and actresses Sophia Loren and Romy Schneider. This was a car owned by some of the most famous names in motor racing, including Juan Manuel Fangio and Briggs Cunningham. Of all the cars of the twentieth century it is one of the most instantly recognized, and most desired.

The 300SL Coupé is a car that holds significant collector value. The Graphite Grey (DB 190) car pictured in this post is coming up for sale by Bonhams at their Les Grandes Marques du Monde au Grand Palais sale, to be held in Paris on February 7th 2019.

You will find the sale page for this car with full details of its history and restoration if you click here.

This car is expected to sell in the range €1,100,000 – €1,500,000

Jon Branch is the founder and senior editor of Revivaler and has written a significant number of articles for various publications including official Buying Guides for eBay, classic car articles for Hagerty, magazine articles for both the Australian Shooters Journal and the Australian Shooter, and he’s a long time contributor to Silodrome.

Jon has done radio, television, magazine and newspaper interviews on various issues, and has traveled extensively, having lived in Britain, Australia, China and Hong Kong. His travels have taken him to Indonesia, Israel, Italy, Japan and a number of other countries. He has studied the Japanese sword arts and has a long history of involvement in the shooting sports, which has included authoring submissions to government on various firearms related issues and assisting in the design and establishment of shooting ranges.