The .600 NE: Chronograph Slaying Power

Much has been written about the .600 Nitro Express, most focusing on the sheer power of the cartridge, power with which to stop a charging elephant, and power to break a shooter’s collar-bone and cause a nose-bleed at the same time. Although I first handled a .600 Nitro Express double rifle almost three decades ago I had not, up until last year, had the opportunity to try shooting one. As it turned out it wasn’t a double but a falling block single-shot that a club member turned up to the range with, and he had intentions to do some load development and chronograph his loads.

He set up the rifle on a properly prepared “Lead Sled” benchrest to absorb the recoil, and attempted to chronograph his first load. That’s when the trouble began, his bench rig was intelligently set up and so there was no problem with that, but the chronograph on a tripod set about ten feet from the muzzle kept getting blown over every time he fired a shot: the .600 Nitro Express generates rather a lot of chronograph toppling muzzle blast. The chronograph was moved further away from the muzzle but it still had a tendency to fall over sometimes, but he got some velocity readings.

There were a handful of us who were keen to assist with the test firing, me being one, and when offered I was not going to hesitate to have a go with a full power load, from off-hand in the “stand on your hind legs and shoot like a man” style: after all, if you think you might get hurt then its preferable for it to happen as a result of you doing something you’ll enjoy. Picking up the rifle the first thing that struck me was that a 17lb single-shot is an awful lot of gun to carry, one would want a gun-bearer to carry it for you until you were ready to do battle. Firing it was everything I had expected, but it added a dimension that I had not expected also, the rifle had a straight stock and that initially sent the recoil straight back, but the rifle also determinedly wanted to rotate vertically from both the recoil itself and the rocket effect of the chronograph slaying muzzle blast. It was something the likes of which I had not experienced before, certainly not at that magnitude: I’ve had the opportunity to shoot various heavy caliber rifles, the largest of which was a very nice William Evans double-rifle in .500 Nitro Express, and it was controllable, and actually a pleasant surprise, enjoyable to shoot. But the .600 was a handful, something I guess I should not be surprised by.

Two lessons emerged from that all too brief encounter of the .600 Nitro Express kind; one being that the rifle design, especially the stock design, needs some specific features to keep the recoil under control. The drop at heel and the angle of the butt both need to not just drive the rifle straight back, but to absorb the vertical rotational forces and direct them so that the recoil pad is pushed firmly into the shooter’s shoulder. With the .600 NE the shooter needs to roll with the punch of the shot and then roll the rifle back down onto the target, and to achieve this the rifle stock has to fit properly and direct the recoil and muzzle blast energy correctly. The second and obvious lesson was the one we all are familiar with: the shooter needs to work up from rifles of low levels of recoil in modest increments so he/she progressively improves their tolerance, and even enjoyment, of the recoil. That requires good coaching, some physical training, and lots of practice, but remembering that the saying “practice makes perfect” is not true: practice does not make perfect, but only “perfect practice makes perfect”.

History

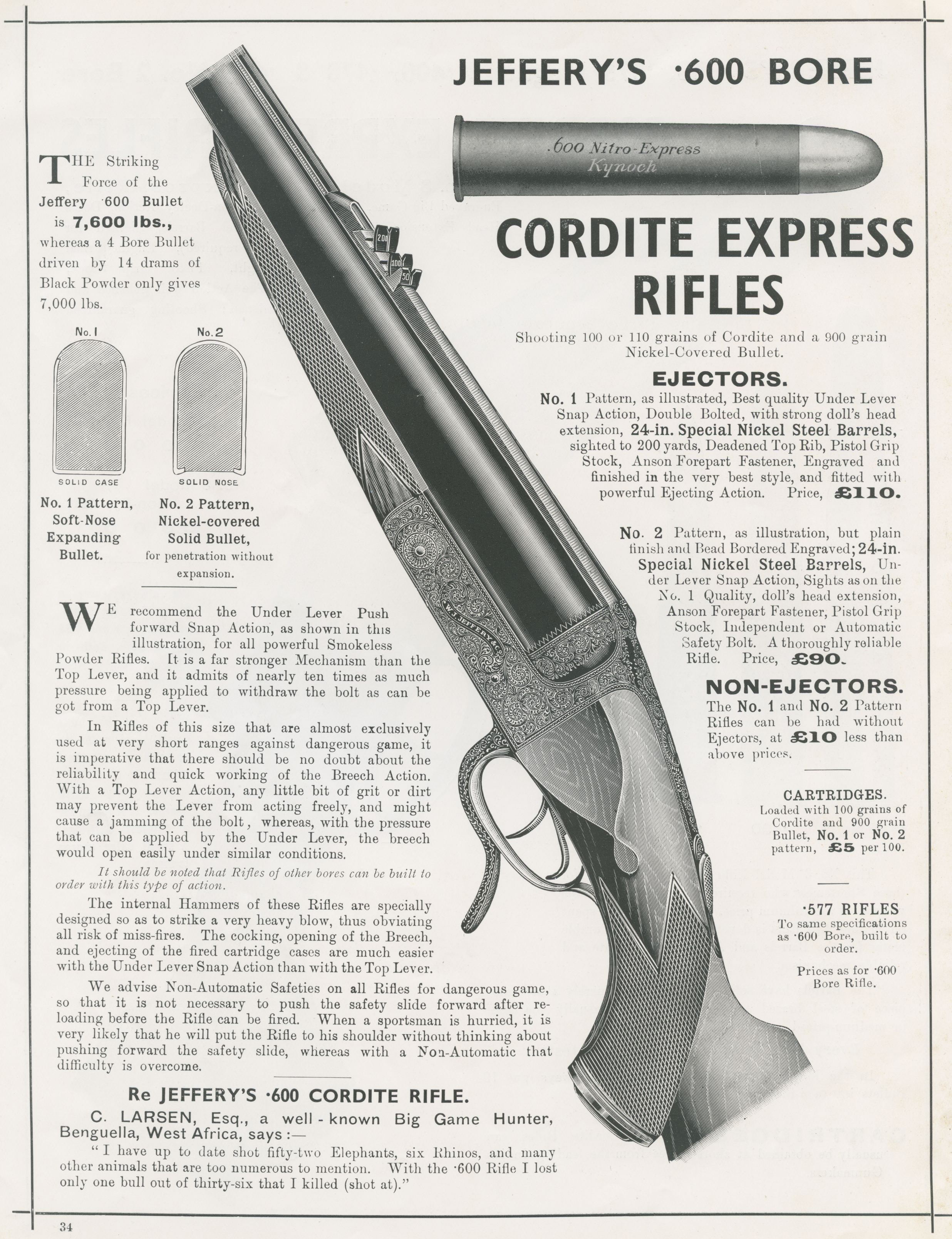

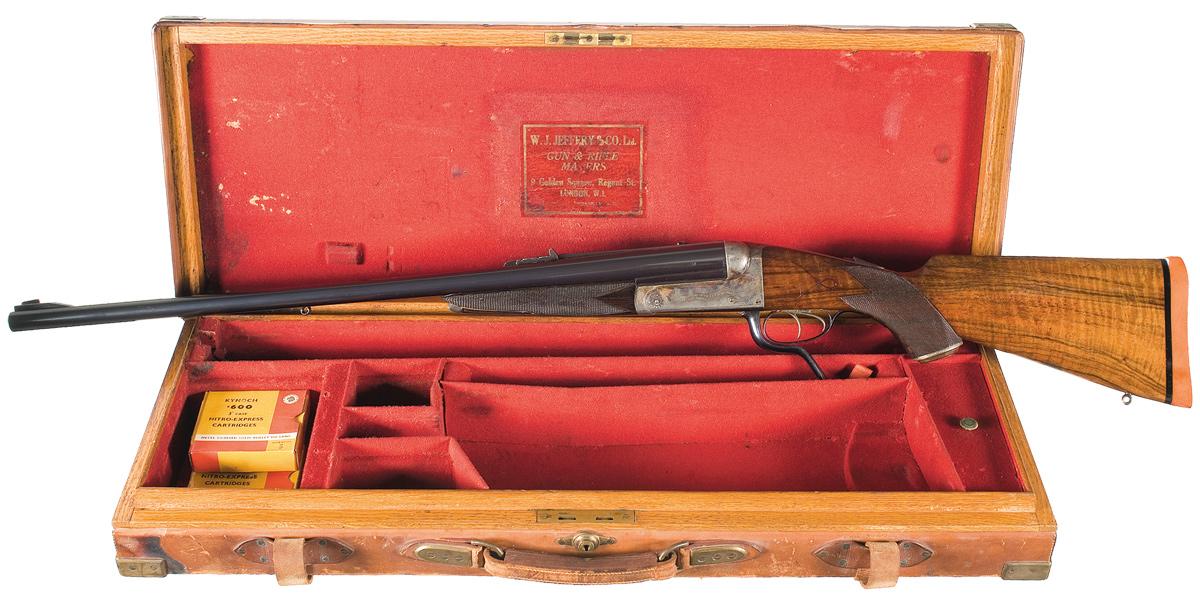

The .600 NE was one of the early Nitro Express designs. It was created by W.J. Jeffrey, a man who would go on to design some of the best cartridges and the rifles to fire them in, such as the .404 Jeffrey and the .500 Jeffrey, both of which are back in production. Development work on the .600 NE most probably took place in the late 1890’s, with Jeffrey making his first .600 NE rifle in 1900.

In order to understand the reason for Jeffrey to create such a behemoth of a nitro cartridge so early in the transition from black powder to nitro smokeless powder we need to remember the 8, 6 and 4 bore rifles and guns being used on large and dangerous game such as elephant prior to that time. W.W. Greener’s book “The Gun and Its Development” gives us an insight into this, and includes a picture of a black powder 8 bore double barrel elephant gun. Typical weight for such a “Mr. Big Ears” stopping gun was around 20lb. Some hunters were not content with even an 8 bore and chose to go up to a 4 bore. If you have the opportunity compare the size of an 8 bore or 4 bore cartridge with a .600 NE and you will instantly appreciate that the .600 NE looks rather small and anemic by comparison.

Jeffrey understood not only the technical design requirements but also the marketing strategies that would be necessary: he understood that the sporting and professional hunters who would be buying a new dangerous game rifle were going to need to be able to trust their lives to it. These people were often in situations where they would need to go into thick cover and get up close and personal with animals that could easily kill them. The rifle they carried into danger had to be able to provide a life-preserving result by not only having the power kill, but to crash through thick bush with minimal deflection and deliver a shock impact sufficient to stop a charge from an animal that might weigh over 10 tons. Jeffrey’s advertisements emphasized the comparative energy of a 4 bore stopping gun and the .600 Nitro Express: stating that the 4 bore hit with a striking force of “only” 7,000 lb while the .600 Nitro Express hit with a 7,600 lb striking force. Testimonials from well known satisfied customers were also used to persuade amateur and professional hunters that they could replace their twenty plus pound 4 bore or 8 bore for a lighter and easier to manage .600 Nitro Express with the expectation that it would help keep them alive and help them achieve the success on the game fields that they were looking for.

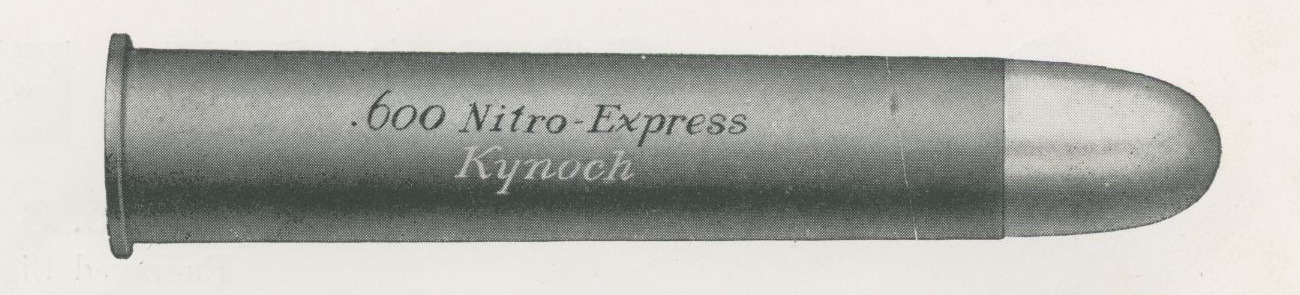

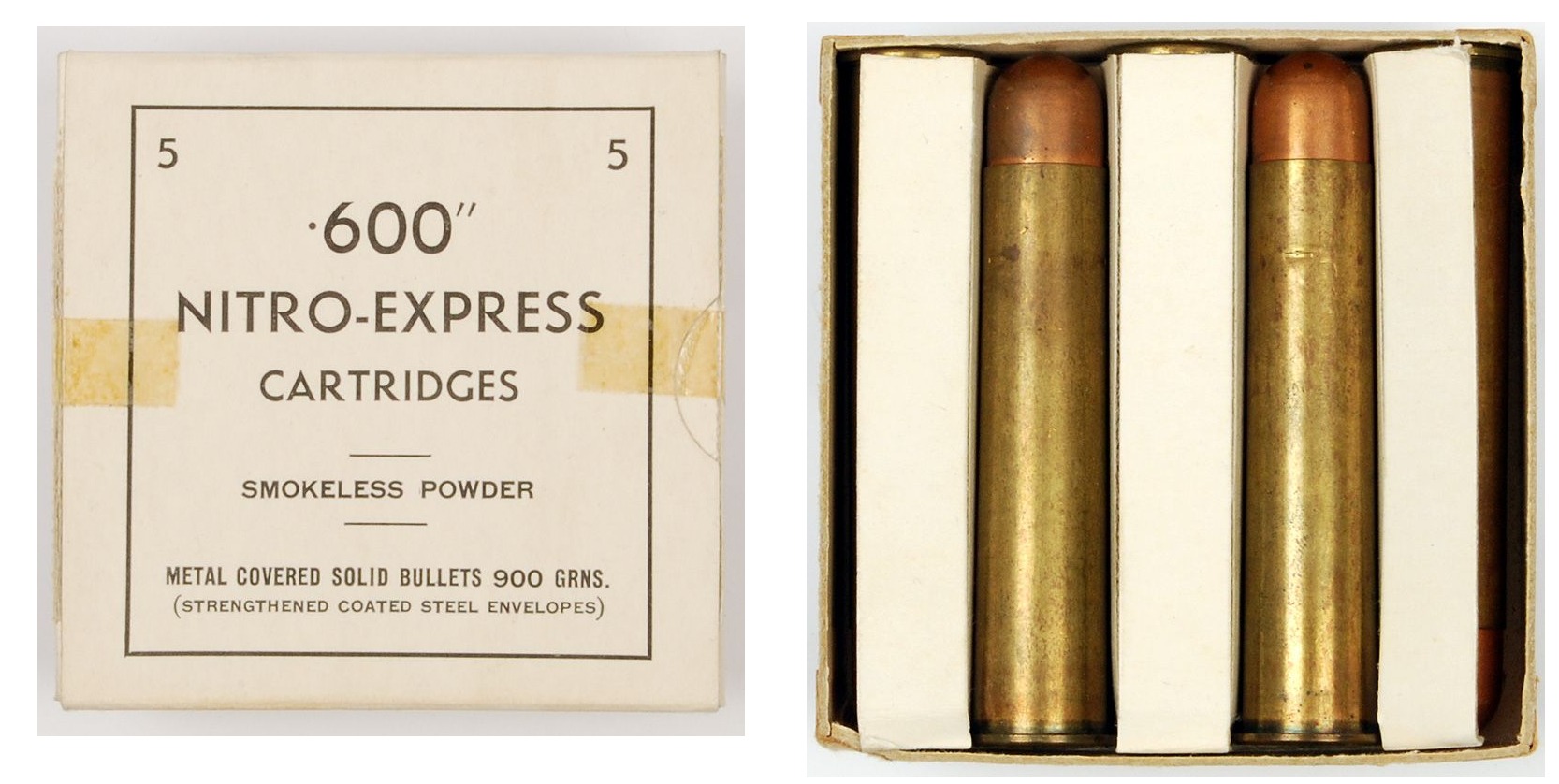

The .600 Nitro Express was offered commercially in two loadings, the lighter load used 100 grains of Cordite behind a 900 grain bullet driving it at 1,850 fps and delivering muzzle energy of 6,841 ft/lb. The heavier loading was for a 110 grains Cordite charge behind a 900 grain bullet and sending it out of the muzzle of the 28″ test barrel at 1,950 fps providing muzzle energy of 7,600 ft/lb. W.J. Jeffrey made rifles in both loadings although his use of the 100 grain loading was better known. The third and most powerful loading is generally thought to have been experimental, Jeffrey only made one rifle for it. This was for 120 grains of Cordite sending that 900 grain bullet downrange at a crisp 2,050 fps and generating no less than 8,400 ft/lb muzzle energy.

Recoil levels determined just how light a rifle could be made; the 100 grain Cordite loading permitted a rifle as light as 13.5 lb or a bit less, preferably a double with a well designed and fitted stock, recoil for such a rifle was 93 ft/lb. For the 110 grains of Cordite loading rifle weight needed to be around 16 lb which kept recoil down to 96 ft/lb. The 120 grain Cordite loading would have required a rifle of at least 17 lb and generated recoil of just over 96 ft/lb.

To put these recoil levels in perspective a 30-06 delivers around 22 ft/lb recoil using 180 grain bullets in an 8.5 lb rifle, a 9 lb .375 H&H Magnum delivers around 42 ft/lb recoil with a 300 grain bullet, and a .458 Winchester Magnum delivers 60 ft/lb from a 9 lb rifle with the 510 grain bullet. So a .458 Winchester Magnum delivers about two-thirds the recoil of a .600 Nitro Express. So if you feel that the recoil of a .458 Winchester Magnum is as gentle as a maiden’s caress then you are probably ready to try a .600 NE.

Of the two commercial loadings for the .600 NE the lightest one was in all probability the most practical, allowing the use of a 13.5 lb rifle while still delivering near 4 bore stopping energy. As 4 bore rifles could weigh 26 lb that means a 13.5 lb .600 NE double rifle could be about half the weight.

Performance

Published velocities for the .600 Nitro Express were determined in a 28 inch test barrel, but many shooters had their rifles made with shorter barrels resulting in lower velocities: a common length for double rifles was 26 inches. However, from a 24 inch barrel the 100 grain Cordite load could be down to 1,700 fps. This would drop the energy down to 5,777 ft/lb, which is still more than sufficient for dangerous game being more than 1,000 ft/lb more than the .458 Winchester Magnum delivers, but which is not in the same class as the black powder 4 bore.

As might be expected, with the advertising suggesting that the .600 Nitro Express was the most powerful cartridge in the world, and with the experience of shooting one being a very impressive experience, people had high expectations of it, expectations that were perhaps too high. There were those who said that the .600 delivered less penetration than a .500 NE or .577 NE, which is true, but professional hunter John “Pondoro” Taylor (author of “African Rifles and Cartridges“) measured 27 inches of penetration with a solid bullet in the skull of one of the sixty or so elephants he shot with it, and 27 inches is more than enough, especially with a .620 inch frontal area.

The .600 Nitro Express was made in three main bullet styles; a “Solid” (i.e. Full Metal Jacket = FMJ) which used a nickel jacket, a soft nose expanding bullet, and a soft nose split which was made for optimum expansion on soft skinned dangerous game such as lion and tiger.

The .600 NE was not just a cartridge for elephants in Africa but was also used in India, often by royalty, not just for elephant but also for tiger hunting from a howdah mounted on the back of an elephant. The .600 NE loaded with the soft nose split ammunition was a potent tiger stopper and because the hunter was sitting in a howdah on the back of an elephant the weight of a .600 NE double rifle was not a problem. The .600 NE was and still is one of the best “brush busting” cartridges ever made, making it perfect for tiger hunting in thick jungle.

The .600 Nitro Express Goes to War

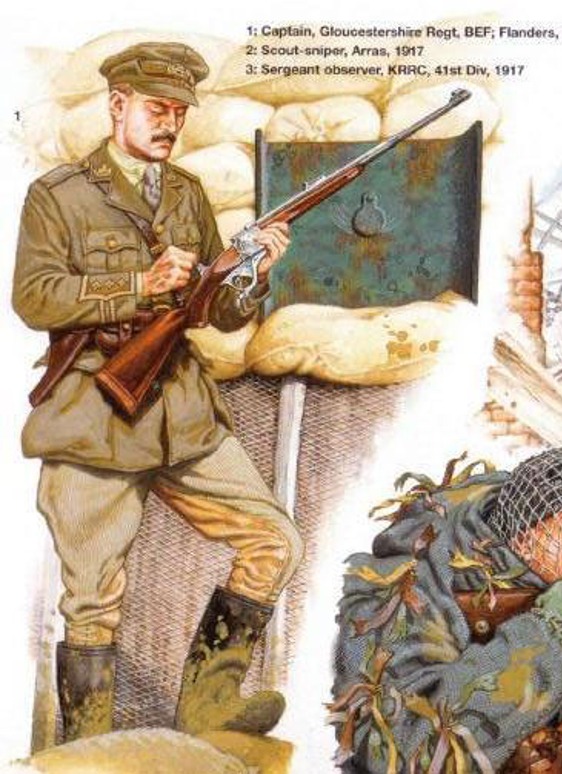

When the First World War got underway in 1914 British and Commonwealth forces found themselves under fire from German snipers who used heavy steel plates to protect themselves, thus frustrating efforts by British counter-snipers to put a stop to their game because the steel plates were not able to be penetrated by the British .303 service cartridge. It didn’t take long for British officers, many of whom were sporting rifle shooters, to seize upon the idea that what might just be good for penetrating the German steel plates, and the sniper behind them, would be a heavy caliber sporting rifle. No less than sixty-two heavy caliber rifles were acquired by the War Office, and that included four .600 Nitro Express rifles.

The officers charged with using these heavy caliber rifles had to adapt their military rifle methods to suit the differences between a .303 and things larger such as the .600 NE. A counter-sniping officer named Stuart Cloete said that “We used a heavy sporting rifle – a .600 Express. These had been donated to the army by big game hunters and when we hit a plate we stove it right in. But it had to be fired standing or from a kneeling position to take up the recoil. The first man who fired it from the prone position had his collar bone broken.”

Suffice to say that the heavy caliber rifles worked well, and also that the British decided that the German idea of shooting from behind an armored steel plate was a really good one: so they invented the tank which was essentially the armored steel plates with machine guns on wheels, and proceeded to turn the tide of the war.

Conclusion

The .600 Nitro Express in its 100 grain Cordite loading in a just over 13lb double-rifle is in all probability the best brush busting dangerous game rifle ever conceived. With 26 inch barrels a double is going to have a comfortable overall length, because the double-rifle action is much shorter than a bolt-action and so keeps overall rifle length down to something like that of a bolt-action with a 23 inch barrel. Assuming that the slightly shorter 26 barrel still provides a muzzle velocity around 1,800 fps the muzzle energy for the 900 grain bullet will be 6,477 ft/lb of stopping power while recoil will be just on 90 ft/lb. It is in short likely to be the largest and most powerful sporting rifle a person can handle competently, as long as they do the training and get the coaching needed, and that the rifle is made to fit them properly and distribute that truckload of recoil in the best way.

The .600 Nitro Express is much more than just a hard kicking oddity: it was designed by people who understood the needs of professional and sporting shooters, and it was created to do everything the 8 bore and 4 bore guns could do, but in a much lighter and more easy to handle rifle.

The big .600 NE was much liked by those with practical experience of dangerous game hunting, including John “Pondoro” Taylor, Bror von Blixen-Finecke (of “Out of Africa” fame), Karl Larsen, and Percy Powell-Cotton. It was chosen by such people for good reason: it delivered the sort of reliable stopping power that made it valuable “life insurance”.

Jon Branch is the founder and senior editor of Revivaler and has written a significant number of articles for various publications including official Buying Guides for eBay, classic car articles for Hagerty, magazine articles for both the Australian Shooters Journal and the Australian Shooter, and he’s a long time contributor to Silodrome.

Jon has done radio, television, magazine and newspaper interviews on various issues, and has traveled extensively, having lived in Britain, Australia, China and Hong Kong. His travels have taken him to Indonesia, Israel, Italy, Japan and a number of other countries. He has studied the Japanese sword arts and has a long history of involvement in the shooting sports, which has included authoring submissions to government on various firearms related issues and assisting in the design and establishment of shooting ranges.